Each of the three films that made up George A Romero’s conceptually linked ‘Dead’ series were quite enigmatic, and now stand as some of the most influential memes in modern cinematic history. This feature for Deathmetal.Org need not explicitly make side references between the musical subculture of which we write to this realm of celluloid, as its popularity with many of death metal’s listening base is well known to those who have insight.

The Night of the Living Dead

Mankind eschews the macabre and the horrifying and in so doing never fully realizes, learns of or utilizes his whole nature. With the exception of a few brave souls, many people prefer to lead idle unchallenged and unexamined lives, if only because the contrary adventure is difficult and exposes one to multifarious existential realizations, including the reality of the ephemeral nature of ones existence. This I conclude is one reason why the horror genre is generally held in such contempt by modern man, when utilized effectively, not only does it confront the eschewed amoral primordial concerns of mans essential being, it does so in a way that is urgent and demanding of ones attention. Having set up his ever safe concrete abode, modern man now hibernates, avoiding existence and its deeper philosophical puzzle’s in favour of sugar coated half-truths such that soothe and reassure him of his “equality” his “individual uniqueness” and his “inherently universal importance”.

The legendary, provocative and incendiary “Night of the Living Dead” does the exact opposite as it confronts, plays on, and plays with the innate primal fears, dynamics and concerns of mankind. Although loosely conceived as an apocalyptic encounter with the forces of the “living” dead, a profound level of psychological insight and evocative symbolism permeates George A Romero’s “Night of the Living Dead” and thus qualifies this work as a true modern masterpiece and a generally overlooked piece of art.

With no little genius Romero effectively lulls viewers into a world viewers can easily relate to by evoking and mirroring significant aspects of our everyday life. Each detail, from the realistically portrayed incompetence of societal authority figures, the naive adherence of people to the demands of the television, the undeniable emotional bond between brother and sister, to the familiar sounds of everyday life, including the incessant chirping of crickets, allows the viewer to fundamentally relate to and plunge into Romero’s world. In fact, the capacity to create a world or setting that so closely mirrors not only a Cold War world obsessed with science and technology but also a timeless, comfortable and familiar, although eerily de-contextualized reality represents perhaps the most important aspect of Romero’s film. These considerations in conjunction with Romero’s capitalization on further cinematic realism, forces the viewer to take seriously the events unfolding within it. Rather than questioning the veracity or possibility of the events unfolding viewers are drawn into reacting, along with whichever psychological archetype they most closely identity with, to the horrifying and challenging events that are taking place.

Although shot in black and white, Romero’s masterpiece lends itself to such profound levels of interpretation that a mere moral and linear evaluation of the film, the characters, or the actions and events therein becomes impossible. To suppose that the contrast between the black and white film and the various gradations of interpretation the film lends itself to was an intentional decision does not appear as dubious as one may suppose. In fact, it seems to coherently present an ingenious tongue in cheek and subtle level of social commentary on a society that was, and still is, increasingly seeing the world in simple morally absolutist ways amidst an inherently complex reality that disdains simple moralistic evaluations.

Through an ingenious development of the story, viewers, while perhaps horrified at the attacking zombies, are not given the pre-requisite moral education or signifying variables that would make it intellectual honest to morally condemn these purely instinctual flesh eating parasites, whose origin can be laid at the feet of man alone. This of course increases the profundity of the film as Romero brilliantly turns the story away from the simple and exhausted “us versus them” or “good versus evil” theme. Viewers are thus forced, beyond the categories of good and evil, to search for, construct and perhaps impose upon the film a more profound meaning.

Romero’s ability to vividly explore, amidst an environment whose intensity is heightened due to the proximity of death, the nature of human relationships, tribal power dynamics, and the capacity for the characters to deal with the prospect of their immanent demise reveals an attempt on part of the film to explore and highlight some of the fundamental aspects of mans primal nature. The intriguing and dynamic character relationships, for example, reveal and augment the inherent antagonism between virtue and vice and we witness concretely the poignant disparity between courage and cowardice, shortsightedness and wisdom, emotion and reason, optimism and pessimism. Viewers also witness the psychological development of each character as they are confronted with possibility of death, themselves symbolizing at a more significant level various timeless psychological archetypes with which it is difficult for the viewer to not identify with.

Additionally, the revelatory and intrinsically personal antagonisms that define each character bear witness to a decisively human element within the film, such that it becomes difficult for the viewer to not empathise with the manifold and sometimes dubious decisions and reactions of each character. This thankfully increases the level of interpretative depth and challenges the viewer; cowardice contextualized instead becomes the instinctual protection of the father, co-operation and perhaps courage resemble stupidity, pessimism becomes realism, optimism becomes fantasy, and so on. In contrast to many latter day films which celebrate an easy and crowd friendly reality that is typically one dimensional, “Night of the Living Dead” successfully transcends this pitfall and successfully mirrors the complexity of the human condition and the multiple variables that determine its structure.

Moreover, “Night of the Living Dead” includes the uncanny capacity to raise an array of questions that unsettle and challenge the mind: Who exactly is Romero referring to as the “Living Dead”? In what ways does technology bring about mans apocalyptic future, has our technological hubris undone us? How does the theme of technology relate to the zombies aversion to fire? How do we relate to and mirror the zombies at an instinctual level? Indeed, a plethora of questions, paradoxes and insights awaits the discerning viewer.

However, in the end what is horrifying about “Night of the Living Dead” is not the flesh eating zombies, it is the capacity for this film accurately reflects man’s condition on so many levels, and to expose the viewer to his or her own primal nature. Above all, what meaning one extracts will depend on each individual’s capacity to plume the philosophical depths implied by one of the main conceptual tenants that drives this movie forward: Only Death is Real.

-TheWaters

Dawn of the Dead

Combustive, feverishly paced and exploitative almost in an infantile way are some of the qualities of the first follow-up to Romero’s original terror classic. By 1978 merciless killing, cannibalism, pile-up of corpses and explosions of gore had journeyed through the forbidden territories of ‘grindhouse’ B-movie theaters all the way to the brink of mainstream as it seemed already the norm to distrust the ‘establishment’. This is satirically extrapolated by the first few minutes where a cop operation gone awry climaxes with a spectacular scene of shooting a person’s head completely off as if it was no big deal.

The colorful but dimensional 35 mm cinematography, financed with the help of Dario Argento’s Italian team, lets Romero to indulge in more ‘hi-tech’ action than before with plenty of fast tracked views from helicopters but also conduct long and gritty depictions of places and people (and of course the zombies) as if we were watching a documentary. He did not originate this technique, but especially in ‘Dawn of the Dead’ mastered it so far that if there is one movie that seems to truly reveal the morbid but ordinary facets of disillusioned 70′s life in the United States, it must be this. The fantasy elements do not seem to be such when immersed in the logical and natural unfolding of the events.

‘Dawn’ is the first of the movies where a point is made of the zombies being less than authentic enemy but rather pathetic victims of a disastrous failure of civilization. The hard boiled soldiers’ execution of zombie families with children is chilling, echoing the amoral vigilante mentality that pervaded a myriad of cult classics of the era. When the supermarket setting allows the script to use both the human characters and the masses of the dead as two ‘classes’ of consumerism, the dimensions of the movie become delightful and tormenting – especially as it is conducted with the flair of a movie magician without an ounce of excess political rant.

Ultimately the angle is cynical since the characters seem very happy with their boring and cyclical existence in the safety of the supermarket, shielded from the dangers of the outside world and appropriately only at the moments of danger does an enlivening sparkle permeate their mind and hands. The intrapersonal dynamics are still reminiscent of ‘The Thing from Another World’ (1951), a veritable science fiction classic where the alien ‘thing’ was deemed almost irrelevant because of the all-around devastation wreaked by social and personal problems of respected figures such as scientists and soldiers.

Despite the passed decades of pushing all-around borders, the gore in the movie still repulses in its humorous viciousness. Besides the more didactic ‘Salò’ and the more amateurish ‘Texas Chainsaw Massacre’, it’s one of the earliest full-fledged exercises in movie brutality, of the bombardment of visual ugliness. It is entirely in parallel with syncopated, jagged, atonal and growled music as medium; it forces the mind to make certain choices while most mainstream entertainment attempts to unify people with hypnotized neutrality and smooth edges.

It’s hard to pick a favorite from the trilogy but there are nuances and an all-out spirit of warfare in this one quite unmatched by the others, which do raise different points of abstraction by themselves. The battle of solitary but teamed individuals against the masses of horrible biological abomination strikes a note which can seem scarily familiar. The message is cryptic but it is spoken loud – there is no more room in Hell…

–Devamitra

Day of the Dead

Undoubtedly the most cynical and dark of Romero’s ‘Dead’ trilogy, ‘Day Of The Dead’ continues the concepts explored in ‘Night Of The Living Dead’ and ‘Dawn Of The Dead’ which to the social anthropologist fall perfectly within the societal contexts of their decade, both in terms of appearance and issues dealt with. 1985′s ‘Day Of The Dead’, the intended third of George A Romero’s trilogy for the most part tackles Cold War paranoia dead on, and conveys a sense of isolation, disorder, and internal conflict that 1978′s ‘Dawn Of The Dead’ hinted at.

Whereas ‘Night Of the Living Dead’ contaminated the countryside, and ‘Dawn Of The Dead’ contaminated greater consumerist society, the third of these films now brings the viewer to a conclusion in where all previous facets of Western human society have been fully violated, with the few to emerge unscathed hibernating in underground shelters where in spite of a common need to survive, greater in-fighting occurs. This film is a much more dramatic affair than any of the previous two, and as a result its subject matter becomes more obtuse. Science and anatomy play a greater role in this film, in which the chief lab technician attempts to find means as of how to reanimate the once living, or do bring about a reversibility to the impulse-only movement of the undead. The soundtrack is mostly synthesized, having an emotive depth not unlike a cross between the scores to Scott’s ‘Blade Runner’ and Argento’s ‘Tenebrae’.

The graphical element of the third of these films is more prominent, the gore more repulsive, the atmosphere more repulsive and suspensive. Some would suggest that the quite lengthy build up of this installment is detrimental to the overall quality of the film, but in the opinion of the reviewer gives an excellence not seen in the previous two installments, the most intelligent and and serious of Romero’s zombie films.

–Pearson

No CommentsTags: zine-video

Metal audiences and listeners, aficionados of a genre that is well known for it’s enthusiasm towards the macabre will always have the generalization of being attached to the horror genre. A very recent

Metal audiences and listeners, aficionados of a genre that is well known for it’s enthusiasm towards the macabre will always have the generalization of being attached to the horror genre. A very recent

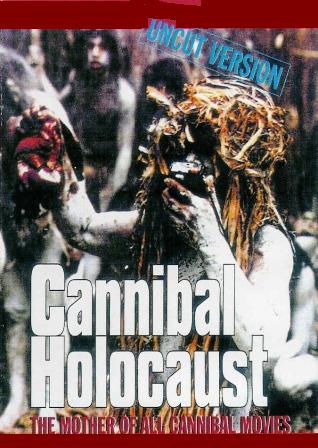

This is by no means the easiest of films to watch. It has numerous flaws and executions within the film that would provoke one to make immediate criticism, for example the sub-par, almost at times robotic acting and unimaginative script, and what could indeed be labelled a lack of cohesion (could this be due to editing and censoring? I am not sure), Cannibal Holocaust never ceases to shock and provoke, as well as provoke immediate questions of ‘who are the real savages?’ and how people might want to generally assess their modern, non-organic way of living.

This is by no means the easiest of films to watch. It has numerous flaws and executions within the film that would provoke one to make immediate criticism, for example the sub-par, almost at times robotic acting and unimaginative script, and what could indeed be labelled a lack of cohesion (could this be due to editing and censoring? I am not sure), Cannibal Holocaust never ceases to shock and provoke, as well as provoke immediate questions of ‘who are the real savages?’ and how people might want to generally assess their modern, non-organic way of living.

The most redeeming features of the film are the soundtrack by Riz Ortolani, which utilises rather dated synthesisers alongside a string orchestra, often interspersed with music that sounds not too dissimilar to Italian religous music, with arpeggiated acoustic guitars playing upbeat music that adds a brilliantly sarcastic touch to an otherwise grim and unrelenting series of violent acts. The usage of hand-held camera is very effective. As opposed to films where every scene is portrayed from a multi-angle perceptive, we see absolute realism for the most part, and is done in a non-perfective, improvised fashion that otherwise contributes heavily to making the film for the most part, very convincing. Cannibal Holocaust is flawed, yes. But it is a triumph of the cold, efficient will. Unlike the humoured (but still excellent) Dawn Of The Dead, Cannibal Holocaust is the work of the cynical sociopath, and seems to metaphorically imply that when one reaches or exceeds a certain threshold of excess, be it due to ignorance, lust, greed, self-indulgence etc, there is not even the vaguest chance of redemption. In a sense, the message of this film is an all-out war against the modern way, and the belief that furthering it to those who are otherwise unwilling to accept it is nothing short of a disastrous consequence. The film also suceeds in that it doesnt moralise about the issues it raises, and also leaves the film open to many possible interperatations. Overlooked by critics for its very bad acting, reviled by the politically correct, adored by much of the exploitation crowd, here is a film which holds truths and meanings beyond a framework that would isolate and sicken many.

The most redeeming features of the film are the soundtrack by Riz Ortolani, which utilises rather dated synthesisers alongside a string orchestra, often interspersed with music that sounds not too dissimilar to Italian religous music, with arpeggiated acoustic guitars playing upbeat music that adds a brilliantly sarcastic touch to an otherwise grim and unrelenting series of violent acts. The usage of hand-held camera is very effective. As opposed to films where every scene is portrayed from a multi-angle perceptive, we see absolute realism for the most part, and is done in a non-perfective, improvised fashion that otherwise contributes heavily to making the film for the most part, very convincing. Cannibal Holocaust is flawed, yes. But it is a triumph of the cold, efficient will. Unlike the humoured (but still excellent) Dawn Of The Dead, Cannibal Holocaust is the work of the cynical sociopath, and seems to metaphorically imply that when one reaches or exceeds a certain threshold of excess, be it due to ignorance, lust, greed, self-indulgence etc, there is not even the vaguest chance of redemption. In a sense, the message of this film is an all-out war against the modern way, and the belief that furthering it to those who are otherwise unwilling to accept it is nothing short of a disastrous consequence. The film also suceeds in that it doesnt moralise about the issues it raises, and also leaves the film open to many possible interperatations. Overlooked by critics for its very bad acting, reviled by the politically correct, adored by much of the exploitation crowd, here is a film which holds truths and meanings beyond a framework that would isolate and sicken many. Promised Land of Heavy Metal

Promised Land of Heavy Metal

Many reissues of underground Metal CDs, especially onto the digipack format of packaging, have removed much of the experience of being immersed in the total artistic presentation that was part and parcel of the infernal sounds it contained on the disc. This is seemingly symptomatic of casual, background, mp3 listening, which feigns a disregard of anything external to the music itself, while at the same time a reduction of whatever’s being heard, to exactly that: ornament. There’s something to be said about the honest ritualism of setting time and space aside in this multi-tasking age of lifestreams and other such convergences of different faced distractions, in order to access deeper and darker worlds. Interesting cover art and a booklet complete with lyrics and liner notes all aid to this end. Peaceville records reissued a large selection of their early 90′s back catalogue several years ago, with some classic albums missing lyrics or important liner notes. Roadrunner records’ budget ‘Two from the Vault’ series were even less impressive, with their dual-offering reducing the content that once accompanied each album to something of infomercial ‘Best of Country Music’ standards. Peaceville, to their credit, did include some interesting bonus material on their digipacked CDs of the first four Darkthrone albums. This was a series of interviews conducted by the Black Metallers themselves, reflecting on the circumstances surrounding each album.

Many reissues of underground Metal CDs, especially onto the digipack format of packaging, have removed much of the experience of being immersed in the total artistic presentation that was part and parcel of the infernal sounds it contained on the disc. This is seemingly symptomatic of casual, background, mp3 listening, which feigns a disregard of anything external to the music itself, while at the same time a reduction of whatever’s being heard, to exactly that: ornament. There’s something to be said about the honest ritualism of setting time and space aside in this multi-tasking age of lifestreams and other such convergences of different faced distractions, in order to access deeper and darker worlds. Interesting cover art and a booklet complete with lyrics and liner notes all aid to this end. Peaceville records reissued a large selection of their early 90′s back catalogue several years ago, with some classic albums missing lyrics or important liner notes. Roadrunner records’ budget ‘Two from the Vault’ series were even less impressive, with their dual-offering reducing the content that once accompanied each album to something of infomercial ‘Best of Country Music’ standards. Peaceville, to their credit, did include some interesting bonus material on their digipacked CDs of the first four Darkthrone albums. This was a series of interviews conducted by the Black Metallers themselves, reflecting on the circumstances surrounding each album. One unavoidable sacrifice to the presentation is the lack of art or logo on the CD itself, because it’s not technically a CD, but a dual-layered CD/DVD. This brings us to ‘Tales of the Sick’, an hour-length documentary about the making of the album, the subsequent touring of the new tracks and its lasting legacy. Conversations with Morbid Angel are limited to insights from David Vincent, whose articulation isn’t quite enough to compensate for the lack of ‘Blessed are the Sick’s lead song-writer and sonic shaman, Trey Azagthoth. And although he doesn’t quite resemble the same blonde-haired Hessian that upheld the Nietzschean spirit of Death Metal since it’s golden age, Vincent provides an interesting commentary on why the album sounds like it does and the obstacles the band faced to achieve this sound. Further to Azagthoth’s tribute in the liner notes, Vincent goes on to describe ‘Blessed are the Sick’ as an attempt to approach Mozart’s compositional style through the lens of Death Metal. Tom Morris of the reknowned Morrissound studios reveals the more technical challenges in engineering one of the most astoundingly crisp and clear sounding Death Metal albums, despite its speed and complexity. Other interviews feature the following generation of Death Metal musicians such as Nile’s Karl Sanders, and a lot of memories from the tours are shared by former managers and sound technicians. As an additional bonus, Earache have included the official music video for ‘Blessed are the Sick/Leading the Rats’, though in it’s original 4:3 aspect ratio. This is a great supplement to an highly influential album, and any real fan of Morbid Angel would do well to add this reissue to their collection.

One unavoidable sacrifice to the presentation is the lack of art or logo on the CD itself, because it’s not technically a CD, but a dual-layered CD/DVD. This brings us to ‘Tales of the Sick’, an hour-length documentary about the making of the album, the subsequent touring of the new tracks and its lasting legacy. Conversations with Morbid Angel are limited to insights from David Vincent, whose articulation isn’t quite enough to compensate for the lack of ‘Blessed are the Sick’s lead song-writer and sonic shaman, Trey Azagthoth. And although he doesn’t quite resemble the same blonde-haired Hessian that upheld the Nietzschean spirit of Death Metal since it’s golden age, Vincent provides an interesting commentary on why the album sounds like it does and the obstacles the band faced to achieve this sound. Further to Azagthoth’s tribute in the liner notes, Vincent goes on to describe ‘Blessed are the Sick’ as an attempt to approach Mozart’s compositional style through the lens of Death Metal. Tom Morris of the reknowned Morrissound studios reveals the more technical challenges in engineering one of the most astoundingly crisp and clear sounding Death Metal albums, despite its speed and complexity. Other interviews feature the following generation of Death Metal musicians such as Nile’s Karl Sanders, and a lot of memories from the tours are shared by former managers and sound technicians. As an additional bonus, Earache have included the official music video for ‘Blessed are the Sick/Leading the Rats’, though in it’s original 4:3 aspect ratio. This is a great supplement to an highly influential album, and any real fan of Morbid Angel would do well to add this reissue to their collection.