About

The Heavy Metal FAQ explores the development of heavy metal as a musical movement through its context in popular culture, and reflects upon the ideological and sociological circumstances that motivated that development. These circumstances are tracked through music theory, symbolism, and behavior.

Version: 2.0 / September 8, 2014

Contents

I. What is Heavy Metal?

- Heavy metal originated as a counter-reaction to the hippie rock of the 1960s and was intended to sound like a horror movie soundtrack

- Heavy metal fused progressive rock, hard rock, and soundtrack styles using the power chord to make phrasal composition

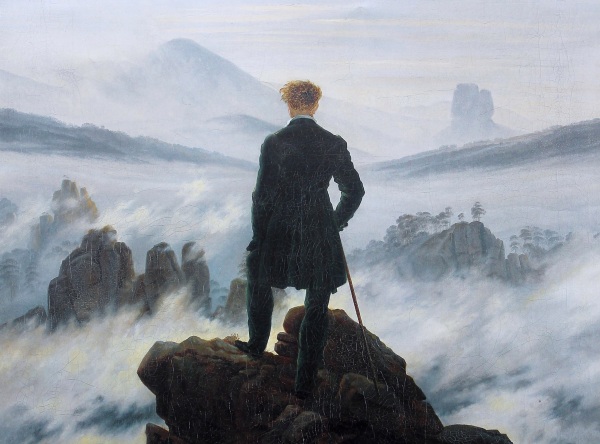

- Heavy metal culture and lyrics resemble European literary Romanticism in its emphasis on the individual and nature, not social mores, dictating value in life

- Heavy metal ideology is an active form of nihilism, in which the individual believes in nothing because belief is not needed as much as a creative, intuitive, warlike principle of vir

- The musical and cultural influences of heavy metal suggest this idea has been injected into the mainstream, but that a constant struggle exists to “norm” it to social mores

1.1 Music

Defining heavy metal requires we look at its many attributes as part of a whole. Heavy metal is is a musical style with certain compositional tenets without which music cannot be said to be heavy metal; however, even more profoundly, it is also a set of ideas that shape its composition, and without those you can have something that “sounds like” metal but does not fit the whole profile of heavy metal. Musically it can be described by the following:

- Composed using forms of the power chord, or a fifth chord lacking a third, in a moveable form based normally on the low E chord. Since these chords lack a third, they are neither major nor minor, and can be played in any position, which lends itself to writing longer, more dynamically melodic or lengthier phrasal riffs.

- Musically “heavy” derived from a songwriting style that emphasizes a return to unison after a resolution of motifs. The promenade-style riffs and theatrical conclusions of metal songs derive from this need, which forms a heavy (emotionally significant) moment later in each song.

- Dark subject matter, and use of heavy distortion, vocal distortion, intensely fast or slow tempos, and other ways of converting that which appears noisy and ugly into a musical language, as if attempting to find beauty in darkness.

- Familiarity with the past musical language of metal riffs and imagery, and ability to build on it, both musically and ideologically.

- A preference for cadence where rock bands would use rhythmic expectation in the pattern of syncopation extended to the beats themselves. Although metal beats are syncopated, this is used internally within cadenced beats and reduces drums to a constant — or “timekeeping” role — which ends phrases on the downbeat.

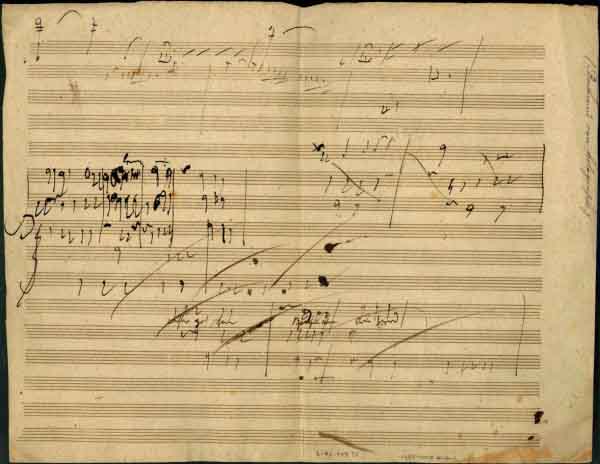

Emerging from the ruins of rock music, heavy metal grew from the conventions of that genre, which possessed an international flair in its use of Anglo-Celtic song structures, European music theory, Middle Eastern and Asian scales, an Arab instrument converted by Spaniards and electrified by Americans, and timbral singing from Africa. These remnants were tempered by a tendency toward progressive rock song structures which approximate those of European classical music; the rhythms of garage punk bands, which come from the first two guitar lessons of an aggressive teenager; and finally, the thematic tendencies of horror movie music, which are generally borrowed from Modernist- and Romantic-era classical composers such as Anton Bruckner, Richard Wagner, Camille Saint-Saens, Johannes Brahms, Robert Schumann and Ottorino Respighi.

The traits of this modernist music — mobile fifths, unison, thematic repetition with inflected motifs, layered harmony and inversion — extend heavy metal beyond its classical roots but also step further backward in time toward the origins of Western music, in that by liberating itself harmonic structures used to identify scale, it returns to the modal, melodically-structured, narrative compositional form originally pioneered by earlier civilizations like the ancient Greeks. When classical music emerged from the rigor of Baroque styling, and ventured into the theoretical but passionate world of the Romantics as defined by Beethoven, it reached a height that demanded a further gesture to continue its artistic specialization. The final point of departure was to liberate melody from the intricate harmonic structure of Romantic music and in doing so to make melody more than harmony the leading compositional tool, so that pieces were defined by the evolution of melody instead of strictly harmonic structure. In this form, which resulted in music that tended toward a nearly chromatic base scale with motifs clustered around it in varied modalities imposed on contact points in that progression of tones, the narrative method of composition reached its most flexible voice. Music became more motif-driven, spurred on by the “leitmotifs” of Richard Wagner, and united a juncture of music, narrative, theatricism and architecture — Bruckner famously referred to his works as “sonic cathedrals” — in which it evolved to within a step away from becoming the rigorously correlated drama, ritual and music of the Greek theatre.

Heavy metal inherited all of this through a modern form because of its desire to escape the cognitive dissonance reaction to modern life. In part, this impulse comes from the metalhead who realizes that the individual is basically powerless, except in a future time when predictions about the negative nature of modern society will come true. Of course, in the now, parents brush that aside and go shopping, stockpiling retirement funds so they can carelessly wish their children a good life before disappearing into managed care facilities with 24-hour cable movie channels. A more fundamental part of this dissident realism is creative. People who see most of society going into denial because they cannot handle their low social status, the dire future of human overpopulation and industrialization, and the negative motivations hiding beneath social pretense, aka “cognitive dissonance,” will often mourn most for the opportunities lost when people value putting their heads in the sand more than finding beauty in life. It is the convergence of these ideas that creates the violent and masculine but sensitive, Romantic side to metal: it is a genre of finding beauty in darkness, order in chaos, wisdom in horror, and restoring humanity to a path of sanity — by paying attention to the “heavy” things in life that, because they are socially denied, are left out of the discussion but continue to shape it through most people’s desire to avoid mentioning them.

This same principle underlies classic European and Greco-Roman art and music, the idea of an aggressive and warlike but wise and sensitive motivation that is both religious and scientific, peaceful and belligerent, because it understands a principle of order to the universe and asserts it because it is beautiful in that it is a “meta-good,” or the harmonious result of darkness and light in conflict. For this reason, it is not moral in the sense of judging as good or evil, and neither fits into the hippie “peace, love and hedonism” approach nor the conservative, market-bound ignorance-is-bliss smoke and mirrors of mainstream music and bourgeois art. Unlike any other musical principle, the one thing that unites the varied borrowings from baroque, rock, jazz, blues, folk, country, classical and electronic music that form heavy metal is this Romantic principle of doing what is right not in a moral sense to the individual, but in a sense of the larger questions of human adaptation to the universe, the conceptual root of “heavy” in metal and what throughout history has been called by a simple syllable: “vir,” the root of virtue in a sense older than a modern moral interpretation as chastity. Vir is doing what is right by the order of the universe discerned by asking the “heavy” questions, and speaks to an abstract structure of right as opposed to an aesthetic one, where the individual picks the non-threatening as an option to the threatening.

It’s a concept album about what once was before the light took us and we rode into the castle of the dream. Into emptiness. It’s something like; beware the Christian light, it will take you away into degeneracy and nothingness. What others call light I call darkness. Seek the darkness and hell and you will find nothing but evolution. – Varg Vikernes, http://www.burzum.com/

For these reasons, where rock has simpler unifying principles (tension between pentatonic and harmonic minor scale) and other forms of music have more clearly genre-specific technique, like funk, which supports a variation not musically much distinct from rock and jazz, metal is both a polyglot and a theory of its own, helped greatly by the flexibility which the power chord bestows. The ability to move chords rapidly without harmonic obstruction led to a desire to write more evocatively phrasal riffs, which led to the riff as basis of composition, which in turn led to longer song structures using a modal sense to unite motifs in an otherwise disparate, chromatic context. This process evolved through the proliferation of sub-genres that marks the development of metal since 1970.

Heavy metal music, as a genre, encloses sub-genres which implement the above list with varying degrees of proficiency, leaving behind rock conventions as they do so for a uniquely metal musical language. While much of this change occurred within speed metal, it was enhanced during death metal and perfected with black metal, and can be seen as an ongoing stratum of concept developed with the first proto-metal album, and continuing in refinement toward a higher vision of itself.

2.2 History

I’ve never thought it an accident that Tolkien’s works waited more than ten years to explode into popularity almost overnight. The Sixties were no fouler a decade than the Fifties — they merely repead the Fifties’ foul harvest — but they were the years when millions of people grew aware that the industrial society had become paradoxically unlivable, incalculably immoral, and ultimately deadly. In terms of passwords, the Sixties where the time when the word progress lost its ancient holiness, and escape stopped being comically obscene. The impulse is being called reactionary now, but lovers of Middle-earth want to go there…[Tolkien] is a great enough magician to tap our most common nightmares, daydreams and twilight fancies, but he never invented them either: he found them a place to live, a green alternative to each day’s madness here in a poisoned world. We are raised to honor all the wrong explorers and discoverers — thieves planting flags, murderers carrying crosses. Let us at last praise the colonizers of dreams. — Peter S. Beagle, introduction to The Hobbit, 1973

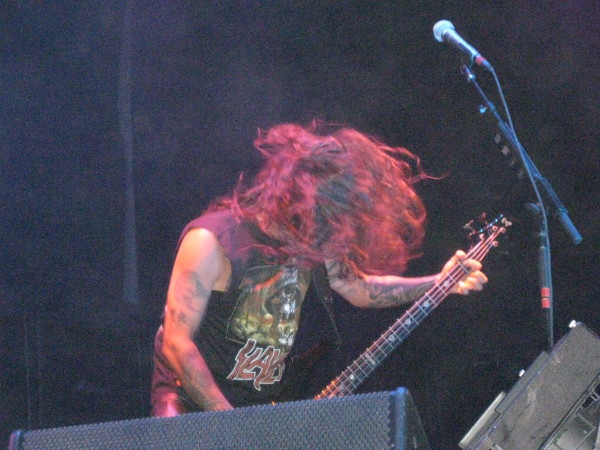

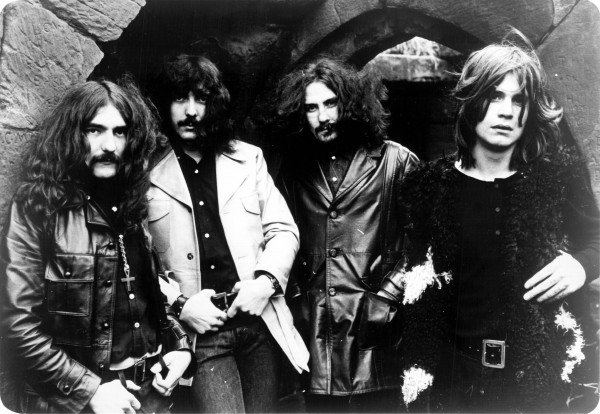

Heavy metal emerged as a distinct musical form with the first proto-metal introduced in 1970 by Black Sabbath. The UK band created a new style of music, equally influenced by extreme rock and horror movie music, that strung together power chords into longer phrases which gave the music a dense and morbid atmosphere. The hippie lexicon of the day referred to it as “heavy” because of the sensations of dark realism and confrontation with reality hidden beneath the human world formed of the consensual reality of socializing, laws and morals.

Hippie culture, in full flower at the time, based its music on popular sentiments of pacifism and love. This was a negative reaction to the innocent but wholesome rock of the 1950s. In contrast, proto-metal brought a dirge of the insignificance of the individual, the brutality of life and the ominous unknown of the future. Where rock bands wrote about personal and political topics (sometimes referred to as “karmic drama”) proto-metal dug into the broader worlds of history, mythology and metaphysics.

The new music instantly attracted those who found both 1950s culture and 1960s culture to be unrealistic, including bored kids from the suburbs where reality was deliberately kept in quarantine and nothing an adult said could be trusted. This upset the music establishment who, despite its criticism of other industries as obsolete and oppressive, was as much a force of calcified “conservative” thinking as was the factory and agriculture establishment before it. Proto-metal made the rock elites look as fat, stuffed-shirty and retrograde as the suited bankers they replaced when the first Black Sabbath album reached number 8 on the UK charts and number 23 in the USA.

Since its inception, the heavy metal genre matured through several generations, sorted by time period:

- Proto-Metal (1970-1974)

- Heavy Metal, Hard Rock/Glam Metal and NWOBHM (1975-1980)

- Speed Metal, Proto-Underground and Thrash (1981-1987)

- Underground Metal: Death Metal, Grindcore and Black Metal (1985-1993)

- Metalcore and Nu-Metal (1995-2005)

- Hybrid Metal: Melodic Metal, Power Metal and Indie-Metal (2005-present)

Black Sabbath changed direction — mixing heavy guitar rock, progressive rock, dark apocalyptic rock and horror movie soundtracks — when Ozzy Osbourne observed that it was “strange that people spend so much money to see scary movies” and wondered if Black Sabbath (then named Earth) could make music with the same effect.

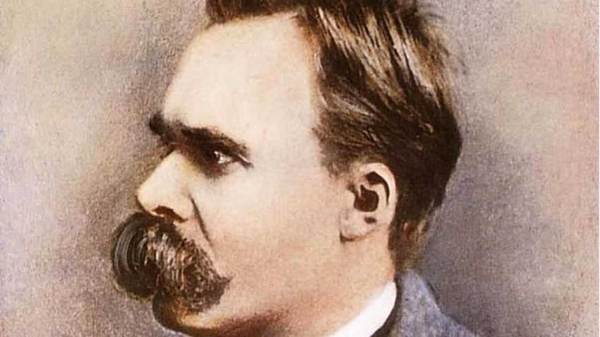

As musicians in the fertile UK rock community, Black Sabbath experienced wide-ranging influences, but heavy guitar rock like The Stooges, progressive rock like Jethro Tull and King Crimson, and apocalyptic rock like The Doors all made their impact on the new music. From the heavy rock, Black Sabbath took its basic power chord sound, from horror movie soundtracks its extended melodies, and from progressive rock its varied and complex song structures. The Nietzschean and apocalyptic themes of the music came from The Doors. Together this mix forged a new style which grew out of rock but by its different approach, also rejected rock.

Through both the horror movie soundtracks that inspired its new sound and the progressive rock desire to approximate the classics of generations past, Black Sabbath inherited a heavy classical influence. This influence eventually absorbed others because the type of chord used in heavy metal, the power chord, can be easily played with the same finger position in any part of the fret board. That ability lends itself to a technique of writing riffs with more phrasal development than rock riffs, which tend to bounce to a rhythm with a very basic harmony; metal riffs could and did move dynamically and approximate a melodic style of composing, and their dramatic horror movie underpinnings encouraged these riffs to imitate what they were portraying, giving them a neo-Wagnerian, operatic feel. This more complex style of distinctive riffing, and its “heavy” tendency to run through multiple motifs on its way toward a theatrical conclusion, was what above all else was to define heavy metal music.

Heavy Metal, Hard Rock/Glam Metal and NWOBHM (1975-1985)

Heavy Metal

The term “heavy metal” refers to both the genre as a whole and a sub-genre of the first wave of 1970s metal music. The successive generation of metal bands streamlined the variety of Black Sabbath into an identifiable set of conventions while merging it with the hard rock influences of Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple. Heavy metal shortened the longer power-chord riffs of Black Sabbath and instead used rock-influenced riffing, melodic lead-picked fills and harmonized guitars to produce a similar sense of structured riff without having to use the full phrasal riffs that require the music to move at a slower pace. This produced two waves of heavy metal, first a basic rock-metal hybrid, and second a revival in the New Wave of British Heavy Metal (NWOBHM).

- UFO

- Thin Lizzy

- Kiss

Hard Rock

Hard rock can be identified by its surface resemblance to heavy metal but use of riffs in the rock style as harmony and rhythm without the dependence on phrase that defines most metal riffs. In addition, hard rock bands tend to stay toward the pentatonic-harmonic minor transitions that define most of rock music, eschewing the darker modes and minor key focus of metal. Hard rock emerged with Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple and The Who which remain its most iconic acts. It also created a hybrid in the form of “stadium metal” or “glam metal” which fused the guitar-oriented stadium rock of the 1970s with early heavy metal, producing bands with a big studio sound and professional songwriting but some of the metal edge.

- Van Halen

- AC/DC

- Guns N’ Roses

Glam Metal

Predominantly a UK movement, heavy metal crossed the pond and landed in Los Angeles where during the early late 1970s and 1980s it became “glam metal,” similar to some of the “stadium metal” or crowd-pleasing variants of heavy metal. This sub-variant of heavy metal distinguished itself by applying Hollywood theatrics and the stadium rock sound to heavy metal, as well as some of the gender-bending aesthetics of big city art rock. In a theme that would become part of the bedrock of internal dialogue among heavy metal bands and fans, metalheads critiqued glam metal for “selling out,” or placing appearance and image before substance in order to become more popular with a vapid and uncritical public.

Already a division emerged in metal paralleling the division between “punk rock” and “hardcore punk” in the punk community: many people listened to metal, but its fanatical fanbase wanted music like that of Black Sabbath but more intense. They did not want heavy metal to become hybridized with rock to become a lighter, more socially acceptable and more commercial form of itself. They wanted to get outside of the consensual reality created by social agreement and wanted the music to lead them. Instead, society wanted to assimilate them and make them “safe,” removing the elements of the music that were not socially acceptable. This fracture spurred the next movement within the heavy metal genre.

- Motley Crue

- Poison

- Skid Row

NWOBHM

In response to the influence of “stadium heavy metal” on both shores of the Atlantic, the New Wave of British Heavy Metal (NWOBHM) attempted to exceed the power of Black Sabbath by incorporating faster punk-influenced tempos and the grander song arrangements of prog-rock bands. Much as proto-metal derived an influence both from proto-punk (Iggy and the Stooges) and progressive rock (King Crimson, Jethro Tull), NWOBHM appropriated the dramatic flair and long song structures of heavy guitar prog-rock bands like Jade Warrior, Greenslade, Aphrodite’s Child and Yes in addition to the rock flair of Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple. Where Black Sabbath tuned down its instruments however the NWOBHM kept theirs in standard tuning and opted for a mid-range sound instead of the sprawling cavernous darkness of the extensive riffs of the proto-metal band. In addition, riffs showed the influence of heavy metal by being less phrasal using power chords, but instead implementing lead guitar — often harmonized as in Judas Priest and Iron Maiden — to create melody between complex patterns of strummed chords.

The new sub-genre also borrowed its intensity from the rising punk movement as well as a Do-It-Yourself (DIY) approach to publishing, promoting and recording its music. The DIY aesthetic in both punk and metal arose in response to the intense commercialization of heavy metal that resulted from a handful of record labels releasing all of the music the public experienced, and that music — like Black Sabbath had in its later albums — tending to become softer, more personal and less critical of larger movements in social change. Instead of relying on major labels, NWOBHM released their own material, promoted with flyers and word-of-mouth, and cultivated an audience who instinctively distrusted commercial and socially-approved material. As a result, NWOBHM maintained its underground status and avoided being inundated by commercialism, and instead sent its most popular bands up into the mainstream where they influenced just about everything else.

- Iron Maiden

- Judas Priest

- Motorhead

- Venom

Styles

Styles refer to aesthetic conventions adopted within multiple genres and do not constitute a musical deviation from that genre but apply a different aesthetic.

“Black Metal” (I)

While musically within the heavy metal realm, aesthetic divisions within that sub-genre inspired future generations to expand upon the concept. Starting with NWOBHM and heavy metal bands Venom and Coven in the 1970s, this style of heavy metal used attitudes and techniques from punk to make a simple but surprisingly dark and expressive form of anti-life art. At first humorously Satanic for the shock value of offending an uptight world, these bands quickly found an audience interested in their blasphemic worldview, which in later generations expanded into the obsession with negativity that is a hallmark of postmodern consciousness, paranoia, and drone existence in western nations.

According to rock journalist Joel McIver’s 2004 book Justice for All: The Truth About Metallica, the origins of King Diamond’s look can be traced to a September 1975 Copenhagen stop on American shock-rocker Alice Cooper’s first solo tour:

It was Alice Cooper. I saw the ‘Welcome to My Nightmare’ tour in Copenhagen in 1975. Even though there wasn’t that much make-up … it changed him completely. He became unreal. I remember the show so well. I was up front – and I thought if I could just reach out and touch his boot, he would probably disappear.

King Diamond’s theatrics, when combined with music heavier than that of Cooper, in turn paved the way for the legions of face-painted metal bands that dot the landscape today. It also subjected King Diamond and Mercyful Fate to accusations of Satanism, which Diamond addressed in Justice for All.

- Venom

- Coven

- Mercyful Fate

“Doom metal”

When bands focus on the slow and moribund, dragging riffs that create atmosphere through resonance of repeated patterns that induce a sense of hopelessness and despair, they continue the Black Sabbath tradition of “heavy” in a new form. Doom metal bands come in two varieties, a heavy metal based sound derived from proto-metal, and a darker chromatic approach which owes its germinal material to death metal. These bands prefer detuned guitars, moaning vocals and lengthy songs which resemble dark passages of sound resonating through subterranean caverns.

- Pentagram

- Saint Vitus

- Witchfinder General

“Power metal” (I)

The marketing department came up with this tasty term for energetic heavy metal that owes its musical essence to a cross between speed metal and prog-ish heavy metal, with bouncy rhythms and jazz-inspired double-hit percussion. At first this style referred to a somewhat emotional, exuberant and over-indulgent form of heavy metal, but as time went on, the style moved to include other genres. In the current time, power metal hybrizes its original heavy metal form with speed metal and injects death metal technique.

- Helloween

- Iced Earth

- Helstar

Speed Metal, Proto-Underground and Thrash (1981-1987)

Speed Metal

After heavy metal became absorbed by the mainstream, upcoming metal bands sought to be faster and more extreme in order to avoid being assimilated, believing that radio and social pressures would impose a dividing line that would keep overly loud, fast and distorted music from reaching a mainstream audience. Speed metal arose from two influences: the NWOBHM bands who usurped the metal community in its last generation and the newly intense sounds of hardcore punk. The pattern of a new genre becoming popular, and changing itself to be marketable even though the result was “false” or “sold out” music, and in turn causing underground musicians to retaliate with a more extreme form, repeats through the history of metal.

The borrowing from hardcore punk gave speed metal a new edge. Hardcore punk bands wrote in the chromatic scale and used impromptu melodies with abrupt tempo and melodic shifts in aggressive, stripped down music that entirely obliterated rock conventions like use of pentatonic scales, pop song structure and frequent tempo and key changes. Unlike pop music or its progenitor punk rock, hardcore punk was “about something,” namely the condition of humanity and human thought. Metal bands from this moment on adopted this more skeptical view of society and its place in history as a whole, which translated the political realism of punk into the mythological-historical view of metal.

Using the muted strum, in which the pick hand rests gently across the strings and produces a shorter and more explosive sound, speed metal bands wrote faster and more complex riffs which they fit into complex song structures derived from progressive rock. The faster speed required more aggressive vocals that were closer to shouting than singing and encouraged a different kind of technicality which emphasized less of harmony and more the construction of riffs and radical shifts in tempo. With the more complex riffing packing more detail into songs, speed metal bands expanded song formats beyond the cyclic verse-chorus that worked so well for metal genres before them and instead diverged into the progressive rock structures that had frequently intruded but never found a uniquely metal expression.

With speed metal albums like Metallica _Ride the Lightning_, songs became mazes of riffs. As a result, bands looked for a way to make their riffs “talk” to one another through an internal dialogue. The result caused riffs to find compatiblity with one another on the level of “shape” or similarity of phrase. Riffs aimed to contrast each other but to keep a narrative going, with each successive riff revealing a new aspect to the underlying truth like a voyage of discovery or the denouement of a horror movie. Late speed metal began its turn toward something more explicitly artistic with Slayer South of Heaven and Prong Beg to Differ, and soon other bands were modifying their own sound to reach this “high concept” goal.

Speed metal suffered a fatal flaw in that, as extreme as it was, it was also rhythmically hookish like a pop song, and soon lesser bands had adopted the style and were making pop music within it. That in turn drove speed metal bands into the public light, and by 1988 it was apparent that the formative days of the genre were over and the long slow descent into selling out had begun. The crucial moment came when Metallica, the band that swore never to release a video, released a video for a song with soft verses and distorted choruses, “One.” Pantera followed this with “Cemetery Gates” which used a soft/hard dichotomy as well. A year later, Metallica unleashed a self-titled album with a new logo and less disturbing lyrics with simplified song structures. The era of speed metal was over.

Thrash

Much as speed metal crafted itself from a hybrid of hardcore punk and NWOBHM, thrash music arose arose from the hybrid of hardcore punk and heavy metal. Where speed metal leaned toward NWOBHM, thrash based itself on more extreme hardcore and the older metal of Black Sabbath. Named after “thrashers” or skateboarders who were prone to like both metal and extreme punk, thrash bands wrote short songs comprised of bursts of metal riffs in punk song format. Lyrics criticized society as a whole and avoided specific political viewpoints for the most part.

Where a punk band would criticize the hold that industry or the army had on politics, thrash bands wrote from the perspective of one of the most disenfranchised members of society, the suburban skateboard punk. With no money, no adulthood, and no escape from the miles of lookalike homes on the floodplain, thrashers criticized society itself as a mistake and pointed out its inhumanities and glaring deficiencies with funny, acerbic lyrics. Songs were often as short as a few seconds and the bands crammed four times as many songs on a CD or LP as your average metal or punk band. For the first time, an underground genre embraced alienation, speaking as if it found no meaning in society and would not want to be allied with it.

Although the thrash genre consisted of only a handful of bands and died out after only a half-decade, its influence spread throughout both metal and punk undergrounds, effectively ending punk by being more extreme and forcing metal to race to catch up. Bands took the humor of the genre and isolated it, producing joke bands like Stormtroopers of Death and Method of Destruction whose sound cleaned up the original messy and abrasive thrash and replaced it with cleanly-defined chords and standardized song structures. Despite innovation in both genres, speed metal was destined to collide with corporate megaculture and thrash was to burn out its intensity as audiences moved away from the extreme to the more commercial in both hardcore and metal genres.

- Dirty Rotten Imbeciles (DRI)

- Cryptic Slaughter

- Corrosion of Conformity (COC)

- Suicidal Tendencies

Proto-Underground

Another movement developed in parallel to speed metal and thrash. In 1982, a UK hardcore punk band named Discharge released an album entitled _Hear Nothing See Nothing Say Nothing_. Unlike most hardcore bands, who carefully tied their riffs to their drums, Discharge let the drums play freely as timekeepers in the background while riffs changed independently. The resulting sound liberated the melodic power of the guitar to be entirely riff-driven and allowed the guitar to lead drums as the primary driver of change in each song. While the punk music that Discharge emanated tended toward a chromatic sound, the new flexibility of this format inspired many metal bands, including speed metal and “proto-underground” bands who established the basic techniques of two genres to come, death metal and black metal.

The new sound inspired bands who straddled the genres which would become black metal and death metal. Although they retained many of the elements of speed metal, these faded away as time went on, as did the use of the muted strum. Instead, bands of this type used a fast tremolo strum in the Discharge style and added extreme vocals caused by shouting or screaming while limiting the sound to highs or lows, producing a natural distortion effect. This type of vocalization originated with bands like Motorhead, The Exploited and Amebix. The new style built their songs around the internal dialogue of riffs that resulted in unique song structures fitting the content of each song, the use of “ambient” techniques where riffs changed independent of drums and instruments supported the riff in layers, and the tendency toward the mythological view of metal fused with the total social alienation of hardcore punk.

Underground Metal: Death Metal, Grindcore and Black Metal (1985-1993)

Where previous generations of metal hoped for acceptance, underground metal hoped for the opposite: it wished to remove itself from the mainstream mentality in addition to being too extreme to be sold out. Instead, underground bands wanted to create an alternate system of recording, publishing and distributing music. Spreading news and music through tape-trading and small “zines” or homemade, xeroxed and low distribution magazines, underground metal gained a worldwide audience of fanatical fans.

Death Metal

The first to emerge from the raw material of Slayer, Hellhammer, Bathory and Sodom was the nascent death metal genre. Death metal strung together chromatic riffs using the tremolo technique to create intricate shapes, or phrasal riffs, that then fit together through a process of “riff-gluing” which fit riffs together like puzzles so that they complement each other while contrasting, causing the mental impression of an expanding landscape or labyrinth as the song progresses. This creates a sensation for the listener of discovery as each new riff puts the previous patterns in contrast in a version of the “prismatic” composition used by Modernist classical composers to make repetition grow more intense through atmosphere. This includes a motif-style arrangement where songs return to themes and riffs fit the atmosphere altered by the meaning of the lyrics, which incorporates a theatrical element like the music of Richard Wagner or ancient Greek tragedies.

The first wave of this technique with Slayer (1983) kept its roots in the combination of NWOBHM and hardcore punk but evolved to become faster, ripping-strum styled metal that shifted with muscle over rigid, ambient repetitive beats. However the second wave — Morbid Angel (1986), Celtic Frost (1985), Sepultura (1985), Deathstrike (1985) — were more obscurely and bizarrely formed from raw innovation and chromatic scales. As the decade waned and humanity seemed further flung into the pit of materialism, death metal reached toward the progressive and explored the extremes of melody (At the Gates), ambience (Obituary), percussion (Suffocation), atonality (Deicide), and progressive music (Atheist). Bands created intricate compositions in which song structure reflected song content as foreshadowed by the sigils of the riff forms themselves, with each successive riff changing context and expanding atmosphere to create a sensation of constant discovery.

Death metal successfully evaded assimilation from extrinsic forces, but instead degenerated within. As more bands entered the genre as the underground grew, the bulk of death metal shifted toward a more percussive and chromatic style, composing their material visually from power chord forms along the bottom three strings of the guitar. This lowered the requirements for entry as did the expanding world of labels and zines which supported them, and standards fell. This in turn compelled bands to turn to novelty to distinguish themselves, and bands began voluntarily incorporating mainstream conventions. Labels seized on this as a chance to form death metal hybrids with rock music, which produced “death n’ roll” and a form of proto-indie metal that left behind the power of death metal for socially acceptable ideas, musical conventions and aesthetics.

Grindcore

Descended from thrash, grindcore took the hardcore punk and metal hybrid and applied to it the death metal tendency to down-tune guitars and distort vocals. Like thrash, it featured short songs with unique “shapes” or structures built around the riff. Unlike death metal, it tended to follow the punk style of essentially cyclic verse-chorus songs with some detours. The genre birthed itself in 1985 with Repulsion and Napalm Death both releasing demos. The more rigid and technical playing of Repulsion contrasted the earthy, organic and chaotic — deliberately off-timed, absurdly down-tuned and discoordinated — style of Napalm Death. From the fusion of these bands modern grindcore was born, but other than a few late entrants was done with its creative output by the early 1990s.

An important side effect of thrash and grindcore appeared in its influence on punk. Toward the middle-1980s, punk bands had spent their fury, and explored instrumentally adventurous and more mainstream-oriented angles like later Black Flag and Fugazi (ex-Minor Threat). Many bands, such as Amebix, Discharge and Cro-Mags, drifted closer to Slayer-styled speed/death metal hybrids. The vast majority built together a hybrid of the more progressive punk styles, the rock-infused styles, and borrowings from grindcore. The result formed a pop-punk variant best exhibited by Jawbreaker, which took the poppy songs of The Descendents and built into the them a convoluted song structure. The most profound change was “emo,” which was punk music that focused on self-pity, sadness and compassion instead of rage. This music verged on indie rock in sound and developed a devout following before it was absorbed by pop and progressive punk.

An important genetic component of death metal, grindcore arose from the ashes of hardcore and thrash as the alienated punk-rockers and sociopathic metalheads of the world sought something more extreme, more evocative of the discompatibility they felt as a process of soul. In 1994, Napalm Death _Fear, Emptiness, Despair_ sounded almost the last note for grindcore as its course of innovation started to veer from the minimalistic to abrasively coarse and simple, death metal-like music with complex jazz-y rhythms. Grindcore, like hardcore, thrash, speed metal and early forms of death metal, continues to this day, but most innovation remains at the aesthetic level and the original thrust has been lost.

Black Metal (II)

Black metal, born to uncertainty and neglected for nearly a decade, flowered in the early 1990s. Arising from proto-underground metal, black metal took its primary influence from Hellhammer/Celtic Frost and Bathory. During the later 1980s the genre essentially suspended itself while bands attempted to find a new sound for the underground metal era. Since death metal had explored a form of structuralism, or phrase-based highly structured music, black metal aimed for ambience. Its earliest acts in its fully realized form detached guitars from drums such that drums kept constant time while riffs changed in an extreme version of the lexicon of Discharge — seen most profoundly on Immortal _Pure Holocaust_, Graveland _The Celtic Winter_ and Darkthrone _Transilvanian Hunger_ — and pitched the classic biologically distorted guttural death metal vocals into a high pitched whispery rasping scream. The bands of this generation deliberately engineered their production to sound like the worst of garage engineering and incorporated the noise and distortion into their music by allowing resonant frequencies to carry their simple melodies in layers like an ambient composition.

I told the producer, ‘Give me the worst microphone you have.’ The sound of the drums, we didn’t do anything to make the sound of the song special. Ten minutes and everything was ready. And he was asking, ‘Don’t you want to do anything, you know, you always have to adjust the sound.’ No! Because it was a rebellion against this ‘good production.’ We called it necro-sound, ‘corpse sound,’ because it was supposed to sound the worst possible. I ended up with a headset as a microphone, because that was the worst I could find. I used this tiny Marshall amplifier, you know this big, because that was the worst we could find.

Black metal arose in part in response to the degradation and assimilation by mainstream intentions that began to crush death metal in the early 1990s. With the rise of black metal, underground metal inherited the rejection of industrial society that marked thrash and some death metal and expanded it into opposition to modernity itself. Frustration with an increasingly liberal West that had become as oppressive as the conservative version, and a new global economy that seemed to be removing culture as fast as it attempted to make every corner of earth safe for business, as well as a Romantic desire for ancient times in which, it was perceived, meaning was more readily attained through tradition and struggle, drove black metal to become not only the most articulated form of metal yet, but the most popular to rise from the underground. After a dramatic series of church burnings, murders, and taboo politics which affected all but a few of the original Norse, Greek and American black metal bands, the genre was captured by hipsters who pandered to a market who wanted the image of extremity without the socially unacceptable views and behavior.

Black metal gained notoriety not only for its acts of guerrilla warfare and urban terrorism against churches but its negativity toward the “fun” culture of rock music that was pervading metal and assimilating it. Deathlike Silence Records, the label started by Euronymous of Mayhem, imprinted its releases with the famous slogan: “No mosh, no core, no trends, no fun.” Black metal band members gave interviews where they decried the “jogging suit” culture that had taken over death metal with safe, solely humorous and pointless lyrics. In the view of black metallers, modern society represented a series of trends which took good sub-genres and exploited them, removing their essence and making them into a standard product like a McDonald’s hamburger. This outlook fit within the desire to make the music as obscure, lo-fi and violent as possible. The goal was total alienation from the herd and its morality.

After its peak in the early to mid-1990s with the Nordic black metal explosion, the genre fell prey to bands who adapted the black metal sound to other genres and made easily-digestible versions of the sound. This flowered into a synthesis with indie rock in the late 1990s, at which point the genre had become little more than an aesthetic style and was essentially abandoned by the original bands, fans and community.

Styles

“Doom Metal” (II)

During this time period, former Napalm Death vocalist Lee Dorrian started Cathedral, a band that borrowed from both NWOBHM band Witchfinder General and death metal to produce a new sound. While doom metal bands of the proto-metal variety such as Black Sabbath, Saint Vitus and Pentagram (US) had existed since the 1970s, this new form of doom metal based itself in death metal theory more than the inclusive rock hybrid of proto-metal. Doom metal thus serves not as a sub-genre, but as a style or technique by which bands play exhausting slow and ponderous music which creates an enhanced sense of darkness and mortal weight among the audience. Doom metal can be either of the heavy/proto-metal variety or the death metal variety. Following Cathedral in the death metal variety were Thergothon, Skepticism and Divine Eve.

“Speed/Death”

Early in the genre, most bands had trouble leaving speed metal behind and some formed a hybrid zone which mixed the techniques of both genres in the form defined by speed metal. A movement to combine speed metal ideals with a more abstract and logical, dark sequence of tones took hold in the form of bands such as Kreator and Destruction, who put together deathy speed metal, or intense hardcore-inspired extremists like Sodom who built three-chord high-speed songs to accustom an audience to enjoying a fast and violent melody. In addition, bands in the United States like Rigor Mortis and Sadus mixed the styles with an infusion of technical playing, which can also be seen on the first Atheist album.

“Industrial Grindcore”

One of the most influential offshoots of grindcore proved to be industrial grindcore as developed by Godflesh in 1991 with _Streetcleaner_. Combining machine-like electronic percussion with layers of distorted guitars, Godflesh created a spacious sound in which intense distortion gave rise to gentle melody and layers of melody created a harmonic landscape through which the motion of the song progressed. The possibilities of this new style stimulated minds in the upcoming black metal and later death metal works, causing many bands to work toward atmosphere and layers of sound in their otherwise traditional metal.

Metalcore: Metalcore and Nu-Metal: (1995-2005)

By 1994, black metal culminated in the most iconic and ambitious releases of its era, most notably Burzum _Hvis Lyset Tar Oss_ and later Darkthrone. At the same time both death metal and black metal languished, a new audience inspired by the headlines of black metal murder and the raw parent-shocking extremity of death metal surged into the genre. This created a financial opportunity for those willing to make music that was death metal or black metal on the surface, but underneath, was something safer and recognized. This new music specialized in avoiding the disturbing political and social themes of black metal and toned down the extreme mortalistic pessimism of death metal to a humorous focus on gore lyrics as exemplified by Cannibal Corpse, who lifted much of this from early grindcore pioneer Carcass.

Metalcore

The new post-underground metal music combined a new style of technical grindcore with groove, “mathcore,” best seen in Dillinger Escape Plan, with the hard rock and heavy metal styles of yesteryear and fitted these to the type of rock-punk hybrid of later hardcore, which evoked a “progressive” style in a punk way by insisting on the highest contrast between riffs to the point of randomness, such that songs cycled as if going between different exhibits in a carnival (and the music often resembled carnival music with its emphasis on polka-like beats and extended cyclic fills). In addition, black metal degenerated into what was called “war metal” which referred to exclusively chromatic, highly rhythmic music which imitated the primitive music of Beherit and Blasphemy without the emotional intensity, resembling more than anything else mid-period hardcore punk given metal rhythms. Some even took this hybridization to its next logical step and mixed crustcore, the genre which linearly inherited from Discharge and Amebix, with nominal black metal to produce “black punk.” Another form mixed with deathgrind to form “deathcore” and “slam,” which emphasized percussive riffing and heavy groove with numerous “breakdowns” or rhythm breaks leading to a half-speed groove.

Nu-metal

Mainstream metal added funk and hip-hop influences to death metal to create a rock-based variant known as “nu-metal.” Using the vocal rhythms of hip-hop in a style inherited from the “brocore” metal of Pantera and its descendants, nu-metal used rock song format and metal distortion to make riffs which were essentially funk- and rock-based but used metal techniques of chromatic fills and strum techniques. Perhaps the biggest nu-metal band appeared in the form of Slipknot, but related acts such as Rage Against the Machine and Marilyn Manson also incorporated these elements. Nu-metal added nothing to metal that hybrid bands had not attempted in the 1980s, but with death metal minimalism and the extremity and imagery of black metal, it became a marketable force at stores like Hot Topic which catered to rebellious teens who wanted to avoid stepping over lines of social acceptance and thus actually damaging their futures. Much as a famous ad campaign related “Banker by Day, Bacardi by Night,” the nu-rebels wanted to have both the merits of sociability with the appearance of alienation.

Blackened Death Metal

In the underground, some tried a new marketing technique and created “blackened death metal” or “black/death metal” which distilled to simple rock-style songs with the simplest form of death metal riffing with melody added. This trend peaked early because of the lack of stylistic distinction of these bands which cultivated rejection by existing black metal and death metal audiences, and their refusal to go all the way to socially safe material as nu-metal and alternative metal had, depriving them of an audience beyond an underground which only grudgingly accepted them. Others reverted to a previously successful form in the percussive death metal of Suffocation but streamlined the result into simpler song structures and added groove in the Pantera style, producing a variant of commercial metal known as “slam” which while it had underground aesthetics failed to uphold the structural and philosophical conventions of the genre and was for the most part quickly discarded.

Hybrid Metal: Melodic Metal, Power Metal and Indie-Metal (2005-present)

By the time the 21st century dawned, metal had almost four decades of evolution under its belt but to most, it became clear that it had stalled. No new genre ideas had emerged and people were rehashing the past. And so it came to pass that what the 1970s metalheads had feared was in process: metal was being assimilated by rock n’ roll and reverting to the mean. All of the sub-genres mentioned in this section fall within the rock world more than metal because they reverse and remove the unique metal method of narrative composition, and replace it with the cyclic harmony-based approach of mainstream rock music, no matter how “extreme” the aesthetic in which it is draped. During this age, metal recombined and hybridized but essentially failed to move forward.

Melodic Metal

Starting with At the Gates Slaughter of the Soul and related releases from Dissection imitators such as In Flames and Dark Tranquility, metal bands realized that they could capitalize on what Sentenced had pioneered in death metal: mixing in the Iron Maiden/Judas Priest dual guitar harmony of melodic leads. While Sentenced took a death metal outlook, and Dissection tended more toward heavy metal in song structure and sensibility, the new genre stirred interest in many because it softened the extremity of death metal and attracted an audience with a more even balance between genders. With the next generation, bands reduced death metal to technique alone and followed a heavy metal/hard rock format. The result then hybridized with metalcore to produce “melodeath” or melodic heavy metal with death metal vocals and metalcore song structure. Bands like Archenemy forged into this new domain which rapidly synthesized itself with the type of high-speed chaotic metalcore produced by bands like The Haunted (ex-At the Gates). This style reached its logical conclusion in Gridlink, who applied thrash aesthetics to technical melodic riffing and came up with 13-minute albums with more riffs than most bands put in hour-long works.

Power Metal (II)

Many metalheads expressed a desire for the relative straightforward approach, riff-centric music and compositional integration of 1980s speed metal. They felt that subgenre avoided the excess and dangerous thought of underground metal while preserving what had eternally made metal rewarding to listen to, namely the strong musicality and structural patchwork that produced a sense of ongoing development. Power metal worked in marginal death metal technique and adopted many of the more rock-oriented riff styles from the NWOBHM, sometimes using death vocals and hard rock riffs. Often these bands developed songs from verse-chorus loops but added transitional or bridge riffs to adopt greater complexity. Picking up on a black metal influence, most power metal bands tended toward fantasy-oriented lyrics heavy on medievalist and Tolkien symbology, although those had some precursor in 1980s heavy metal bands like Helloween and Omen. Many modern power metal bands of the Blind Guardian style also feature a use of vocal melodies that resemble those found in gospel and inspirational music, tending toward an upward tonal swing at the end of each phrase.

Indie-Metal

During the 1990s as death metal and black metal surged, indie rock had also gone underground while alternative rock dominated the radio and video channels. Originally born of the migration of DIY punk bands upward into a form of simple, folksy and low-fi rock, indie rock expanded in the 1980s as a method for bands to achieve a reach outside their local communities without becoming dependent on major labels for the same reason that punk bands opted for self-release. At the time and throughout the 1990s, releases that were not on major label imprints found themselves relegated to specialty stores and mail order. As indie matured it crossed-over with another minor-key genre that in opposition to the bombastic and egotist of mainstream rock became self-effacing and even self-pitying, emo. With the emo-indie fusion independent music expanded from a category in the 1980s to a sub-genre of rock music in the 1990s with its distinct sound.

Many noticed that indie bands like My Bloody Valentine and Sonic Youth were very close to black metal, as both used high sustain distorted guitar to create ambient waves of sound, and hoped to find a way to bridge the two despite radical differences in composition, outlook and spirit. As black metal burned itself out, first with imitators and then substitutes like war metal, indie-metal arose first in the black metal genre with crust/indie/emo/black hybrids. This idea spread when Sonic Youth guitarist Thurston Moore joined “black metal supergroup” Twilight, whose sound resembled drone/indie more than black metal. The headquarters of this scene was San Francisco record store Amoeba Records, which began stocking black metal in the late 1990s and recommending it to its clientele of urban indie-rock hipsters. Another big influence starting in 1995 was Swedish band Opeth who took on the death metal label but whose music, with its acoustic verses and distorted choruses, more resembled nu-metal or alternative-metal without the bouncy rhythms and served itself with a certain projected ostentation — “you wouldn’t understand this, it’s too deep and technically advanced” — that won it many fans among the lowered self-esteem youth who shop at Hot Topic.

The first salvo of the indie-metal revolution came through bands like Isis, Gojira and Mastodon who combined proto-metal with indie rock and progressive pop punk, creating longer songs that used metal riffs and aesthetics but other than superficially entirely resembled what the previous generation of indie rock and emo, notably Fugazi, Jawbreaker and Rites of Spring, had made the mainstay of their own successful careers. As the “melting pot” of indie metal continued, other styles emerged, such as “sludge” which erupted from Eyehategod’s punk rock take on the slowed-down dirges of Black Sabbath and Saint Vitus. Other bands took inspiration from the rising “progressive metal” movement which Dream Theater popularized with its mix of heavy metal and light progressive like Rush, and as bands like Cynic and Atheist drifted further into jazz technique, this snowballed together and formed a set of techniques which were recognized as more difficult than standard rock playing thus desirable. Further indie rock crossover occurred when Nirvana drummer Dave Grohl formed Probot, a metal band that sounded more like alternative rock (Grohl’s former bandmate, Kurt Cobain, identified Celtic Frost as the major influence on Nirvana).

Eventually this spread outward through “technical death metal” which, inspired by Gorguts _Obscura_ and other works in the death metal genre, applied death metal aesthetics and technical playing to an indie/death metal/metalcore hybrid. At this point an aggregate, this music followed more of the mainstream path, mixing the light jazz of the 1970s and 1980s with progressive heavy metal technique and indie rock. Its sense of technicality arose from the percussive death metal bands following Suffocation, Incantation, Malevolent Creation, Immolation, Gorguts, Pestilence and Deicide who incorporated intricate rhythms and “sweeps” which sound notes cleanly moving from lower to higher strings on the fretboard, but in the newer form this technicality fit into the late hardcore model of songs which aim for maximal contrast and minimal coherence beween riffs. With that in mind, this style was probably always misnamed as “technical death metal” because it has little in common beneath the surface with death metal, and much more in common with indie-metal.

- Filter

- Pelican

- Opeth

2.3 Styles

Rhythmic

Percussive

The major innovation of speed metal was the muffled, explosive strumming of power chords to produce a sound of impact and resurrect the power of rhythm guitar in rock music. This creates a sound that is both conclusive and demanding, which in turn requires greater coordination with drums and for rhythms to end toward a hard conclusion, not an open cadence. This style defined speed metal, but spread into death metal and other genres as a secondary technique.

- Exodus

- Prong

- Suffocation

Phrasal

Riffs can be played with a tremolo strum to increase sustain on each note creating an effect much like that of playing the riff on a violin, which then makes its melodic component and “shape” or the patterns of its tonal motion and rhythm combined define the meaning of the riff. Phrasal bands use fast strumming to make riffs that talk to each other on the basis of contrast and similarity in phrase, allowing the band to fit together different riffs to make an internal dialogue so that the sound moves forward by successive revelations from the contrast of riffs. This creates a clear narrative structure and allows more riffs per song.

- Slayer

- Morbid Angel

- Incantation

- Immortal

Textural

Some bands use multiple speeds in the way they strum their riffs, producing a texture within the ostensible riff composed of notes, which in turn creates an ambient effect by relegating drums to timekeeper and taking over the lead role for rhythm with the guitar. Textural riffs tend to emphasize internal divisions of rhythm and create consistency through using these textures like motifs shared between riffs, advancing the song through internal dialogue between the textures.

- Unleashed

- Fleshcrawl

- Bolt Thrower

Trance

A trance rhythm uses repetition of a simple phrase to create atmosphere through expectation and then layers additional compositional elements on top or (or texturally, within) that phrase. Like metal itself, this style is easy to do, and hard to do well. It requires a spacious and basic chord progression to work with and an ability to use texture, melody and structure to expand upon that initial setup. As with prismatic construction, the “sonic cathedral” effect creates a sound tapestry through addition or subtraction of harmony, and provides powerful but somewhat linear song structures.

- Burzum

- Molested

- Von

Structure

Cyclic

In the most common type of song structure, songs are constructed around a verse-chorus pair that has a turnaround, bridge or solo section before returning to repetition of its main theme. This somewhat binary construction alters that cycle only to provide some sense of peak before returning to the norm. In such songs, conclusions are equal to precepts; that is, the song returns to the same position where it started. This is ideal for songs that express emotion about personal issues, like love and sex, because the singer does not want the world to change; he wishes it to remain static, but for this one alteration, which is the acquisition of the beloved/belusted, which is often seen as fulfillment in lieu of the world around him becoming something he enjoys more. “If I only had you, I could put up with the rest” might describe this mentality. Verse-chorus song construction also finds popularity for its ease of construction, because like opposite ends of a piston cycle the two parts of the binary reinforce each other, which allows artists to focus on harmony and soloing.

- Venom

- Motorhead

- Exodus

Narrative

As the craft of songwriting becomes more complex, a need arises to organize riffs internally by their relationship to one another instead of by their general relation to a harmonic principle as can be done with binary cyclic songs. This requires that the riffs create an internal dialogue in which the shape of each riff comments on each other and shows a chance in relationship to an underlying idea, so that each new riff expands on the context of the old and allows them to be repeated — albeit less than in a cyclic form — in a way that takes advantage of an expanded context so that each successive riff reveals more of a slowly emerging idea. In this style, which more resembles a topography than the neat circles of binary songwriting, songs tend to take narrative form of either a purely motif-driven type which conforms to a story told within the content, or in a more abstract form where the narrative appears in immanent form from the interaction of the riffs themselves. In narrative songs, structure fits content rather than adapting to a pre-ordained form; in some classical music, form is highly articulated to reflect a certain type of story that is to be told, and there the two impulses find parity. In death metal, where the highest evolution of the narrative form occurred in metal, initial riff shape approximates a metaphor for the germinal content, which then in turn shapes song structure around it, more like a form of power chord poetry than a strictly symbolic use.

- Demilich

- Incantation

- Morbid Angel

Layered

A song format brought to its height by technology, layered songs create a single unifying element and then place additional instrumentation around it both in support of it and by doing so, as a method of subtly altering context to change the overall impression of each cycle. Originally the province of collaborative improvisation which by necessity incepted through a simple, repetitive and harmonically open phrase played by one instrument so that others could join at will, with electronic music this form appeared as “dub” built around a sampled and sequenced significant element to which other repetitive sounds were added. Layered music allows the addition and subtraction of layers to manipulate the sonic form as a whole and influences its audience by atmosphere, or the sensation of each cycle as changed by the alteration of its layers which builds upon the trance-like unifying element. This shows up in metal more as a technique, such as allowing a riff to gradually find support in drums, bass and vocals, and saw its predominant use in death metal as this form. Frequently, bands break to a riff, mirror it in other instruments, then double the pace of at least one of those instruments and possibly add a second but closely related riff over the top to build intensity without breaking from a riff form.

- Bolt Thrower

- Dismember

- Monstrosity

Flavors

New York Death Metal (NYDM)

Building on the techniques of speed metal, these bands mixed the percussive style of explosive muted-strum riffing with dark and morbid riffing exhibiting doom metal influences. Often song structures took a more literal direction and resembled musical essays commenting on different aspects of a form before peaking and then returning to stability. This style takes two forms, the guttural blasting death metal variety and the more intricate but mid-paced style.

- Suffocation

- Immolation

- Morpheus Descends

Florida Death Metal

Florida death metal bands created a style which emphasized repetitive riffs closely mated to drums and pulsing rhythms. The result borrowed more from heavy metal and speed metal than most death metal, but provided an easily-grasped form which increased the renown of the genre through defiant, monstrously simple and direct metal.

- Deicide

- Monstrosity

- Death

Swedish Death Metal

Bands of this variety used a new type of spikily distorted guitar, formed by applying high-intensity distortion via pedal and overdriving it at the amplifier as well, which created high sustain to the guitar and facilitated development of melody. In addition, the early bands in this style borrowed the “d-beat” (a broken rhythm between snare and bass drums) from Discharge and applied it to simple melodic riffing to create a style both savage and beautiful. Bands initially applied the traditional Swedish melodic aptitude toward death metal that initially favored complex riffing, but later reverted to a heavy metal form with speed metal influences that used cyclic song structures to make the most popular version of this style.

- Carnage

- At the Gates

- Entombed

Progressive

Continuing the progressive tradition in metal from its influences in late 1960s progressive rock, death metal bands upgraded the wily fingered “technical” death metal of a previous generation with influences from jazz, classical and 1980s guitar shredder music like Joe Satriani. For a time, many of these bands found a unique voice for application of progressive rock ideas in metal without simply recapitulating past works, but with the popularity of Dream Theater it became clear that a huge audience existed for that which facially resembled classic progressive rock and had simpler internal structures underneath. Thus progressive music in metal had two generations, a native one and an externalized one which gradually became a more rock-like form that retained metal riffing and lost all other influences.

- Atheist

- Gorguts

- Pestilence

- Obliveon

Göthenburg/Melodic

From Göthenberg, Sweden, came a series of bands emulating At the Gates by making technical death metal with heavy metal influences and technical riffing. After At the Gates released _Slaughter of the Soul_, this form changed into mostly heavy metal with death metal tremolo strum and lots of melodic intervals. At that point, it essentially became assimilated by power metal.

- Dissection

- Sacramentum

- Unanimated

Deconstructivist

Chaotic and nihilistic blasts of short information in three-note riffs founded this style, which through reduction of assumed musicality focused on the information it communicated, but ultimately recapitulated the punk tendency toward disorder and thus became assimilated by punk styles or the art-rock tendencies to which punk migrated. This style differs from the rest of metal in that it attempts to break down or deconstruct attention to a single point of focus, rather than enwrapping multiple points of focus into a single narrative, but resembles early thrash and grindcore in its construction and the arc of its evolution.

- Impaled Nazarene

- Havohej

- Ildjarn

Epic

Descended from the devotees of Bathory Blood, Fire, Death, this style aims to create a mini-opera out of albums made with grand concept, “symphonic” instrumentation or added layers of keyboards and synthesized voices, and song structures which emphasize aggression rushing into vast and spacious processionals resembling the coronades of classical music. Often like its forebear Richard Wagner this style focuses on a fusion of folk tales, nationalism and mythology.

- Emperor

- Bathory

- Graveland

Folk

Arising later in the metal canon but within the 1990s, this style took folk forms and hybridized them with metal. In this instance, folk refers more to the European music tradition of songs passed along in local areas over the generations, and less to the rock-infused variant of American country which derives influences from Anglo-Germanic folk music adapted to the simplest cyclic form possible.

- Enslaved

- Empyrium

- Skyforger

Neoclassical

Deriving many of its influences from the late-period synthpop like Dead Can Dance that fused ambient/industrial with world music, rock and classical influences, neoclassical influences in metal attempt to resurrect classical song structure and spirit in metal music. In heavy metal genres, it tended to manifest in borrowings from classic melody used in lead guitar solos; in death metal, it manifested in structure that emulated the grandeur, power and breadth of classical music. Some bands, such as Massacra, described themselves as “neo-classical death metal” while others alluded to this influence only in interviews.

II. Metal as Concept

- Metal is a form of composition rather than a specific music theory unique to metal but also found in classical music.

- Metal bases its beliefs around the concept of _vir_, or aggressively doing right without reference to individual preferences.

- Metal culture is not counter-culture, but a rejection of it and mainstream establishment culture alike.

- Metal theory involves a number of techniques used to make sonic texture and narrative composition.

2.1 Theory

“All music is the same.” – Paul Ledney (Profanatica, Havohej, Incantation, Revenant, Contravisti)

Heavy metal music uses the same music theory that propels all Western music: the diatonic scale and its harmony, the same rhythmic divisions and calibration, and the same instrumentation. Rock music arose from polyglot influences; heavy metal injected Modernist classical via horror movie soundtracks and then in the next generation stripped down composition to the barest elements and then built it up again into a language of its own. Thus much like rock exists within Western music, metal exists within rock, but by dint of its entirely different approach and outlook constitutes a separate genre.

What distinguishes metal is its use of riffs as motifs or phrases. These allow metal musicians to unite two highly contrasting points through an intermediate journey composed of dialogue between riffs in (usually) the same key. Through internal dialogue, these riffs negotiate a balance such that the song arrives at conclusions different from its starting point and can repeat its main themes in a new context established by the changing shape of the riff. As a result, metal song structures vary more than those of any other popular genre and contort themselves to the unique needs of each song. However, since metal is still a form of popular music, this variation occurs as an addition to the dominant verse-chorus structure, much as metal is an augmentation to culture as opposed to a counter-reactive, revolutionary force.

Through this method heavy metal inherits the technique of modernist classical composers like Anton Bruckner and Richard Wagner, who used both leitmotifs and the prismatic technique of repeating themes after variation to increase intensity of mood, fused with the technique of hardcore punk musicians that stripped aside the conventions of rock to write in keyless chromatic phrases. It inherits its song structure from the progressive rock like King Crimson or Jethro Tull that was part of its founding inspiration, but wraps it around these phrasal compositions inspired byhorror movie soundtracks that were derived directly from modern classical. Using the instrumentation of rock, metal is able to channel its more traditional heritage and, like its founders Black Sabbath, oppose the dominant illusions of a time where pleasant mental escapism pretends it is combating a dominant undercurrent of decay based in human evasion of reality. Metal is not just “not rock”; it is anti-rock.

In this sense, heavy metal may be the first “informational” genre of music in that its riffs act more as a pattern language or design pattern to signal the intent of each motif than they serve in the rock music role of filling harmonic space to accompany a vocal which defines the melodic progress of the song. These motifs emerge from a sense of mimesis, or imitation of what exists in reality, but in the case of metal this imitation seems to be not of physical objects but logical objects. Metal is about information; information forms a level that unites thought, matter and energy by putting them in the same arrangements and thus having the same informational outcome. Thus a dream can metaphorically resemble reality, and the objects in reality can be re-shaped by the actions of the dreamer corresponding to events in the dream, and even the cycling of energy can be changed by an alteration in form of physical objects based on their abstract design or thought-based properties. This Platonic similarity explains much of the evocative power of metal: its riffs resemble sensations of reality if not reality itself, much like how horror movies speak through metaphor about the horrors of life itself.

The intensely ritualized vocabulary of metal riffs resembles other types of design where repeated patterns are used in similar fashions; the difference is that in metal this language of patterns is used toward fantastic and not functional ends. Architect Christopher Alexander, who designated the term “pattern language” to describe how similar needs produced similar architectures and how those in turn effected the layout of whole communities, explained the importance of pattern languages and their use in producing spaces for humans to live in:

When I first constructed the pattern language, it was based on certain generative schemes that exist in traditional cultures. These generative schemes are sets of instructions which, if carried out sequentially, will allow a person or persons to create a coherent artifact, beautifully and simply. The number of steps vary: there may be as few as a half-dozen steps, or as many as twenty or fifty. When the generative scheme is carried out, the results are always different, because the generative scheme always generates structure that starts with the existing context, and creates things which relate directly and specifically to that context. Thus the beautiful organic variety which was commonplace in traditional society, could exist because these generative schemes were used by thousands of different people, and allowed people to create houses, or rooms or windows, unique to their circumstances.

Each pattern is a three-part rule, which expresses a relation between a certain context, a problem, and a solution. As an element in the world, each pattern is a relationship between a certain context, a certain system of forces which occurs repeatedly in that context, and a certain spatial configuration which allows these forces to resolve themselves. As an element of language, a pattern is an instruction, which shows how this spatial configuration can be used, over and over again, to resolve the given system of forces, wherever the context makes it relevant.

This sense of a pattern language producing design patterns specific to a certain function and adaptive to context resembles the descriptions of another great thinker. The Greek philosopher Plato wrote of divine forms which explained the patterns behind everyday objects and the reasoning for their existence. He viewed these forms as a truer representation of reality than a focus on the tangible and immediate material example of any given object. His description of these forms is as follows:

[There are] men passing along the wall carrying above their heads all sorts of vessels, and statues and figures of animals…which appear over the wall. Some of them are talking, others silent…[The prisoners] see only their own shadows, or the shadows of one another, which the fire throws on the opposite wall of the cave…And if they were able to converse with one another, would they not suppose that they were naming what was actually before them? And suppose further that the prison had an echo which came from the other side, would they not be sure to fancy when one of the passers-by spoke that the voice which they heard came from the passing shadow? To them…the truth would be literally nothing but the shadows of the images.

In this metaphor, Plato describes what forms are by describing what they are not. In the context of metal, the forms of riffs are not strictly mimetic; they do not imitate, for example, a chair. They imitate the mental experience of someone perceiving an object in an event or process and the resulting unity between that thought and the experience. The narrative riff style encourages the expression of a process through a story, such as how a person came to a realization, and the interlocking prismatic riff constructions emphasize this condition of change restoring order but amplifying its context and thus meaning. In this sense, metal reveals the underlying content to objects and experience as is relevant to the narrator. This fits with the metal idea — derived from Romanticism — of the lone individual trusting an “inner self” where truth and lie can be discerned and meaning can be found. The metal habit of knitting together riffs to tell an evolving story exemplifies this idea.

The narrative construction of heavy metal — especially underground metal, in which the genre found full expression after three generations — joins it with an elite fraternity of other genres in which song structure is specific to context. In particular, classical music, cosmic ambient bands and progressive rock tend to use this structuring scheme. It enables them to both experiment within a rule-based system where a language is shared with the audience and thus can be used by reference to incorporate a wide variety of ideas, and also to adapt their music as specifically as possible to its topic. This creates a certain “poetry” of the song where the lyrics explain what occurs and lead changes in guitar which determine the directional change of the song. In classical music, the song forms that developed over centuries reflected the generative patterns required for certain types of context, which in art means “content” and “topic.”

Metal creates an extremely naturalistic form of information music as a result. Its songs, like structures found in nature, use simple ideas expanded upon by their interaction over time so that through the internal dialogue of riffs, a journey unfolds and reveals the intent behind the content as framed by the artists. Much like in a poem, where the meaning is not “spelled out” but must be decrypted by the mind of the reader who compares it to past experience and uses analysis to unconver its relevance and metaphor, metal songs resemble subconscious ideas or even the shapes of memories and experiences in our minds. Like abstract art, the unconscious metaphor indicates a similarity and creates a connection between listener and topic.

A physicist, conceiving systems of differential equations, would call their mathematical movements a “flow.” Flow was a Platonic idea, assuming the change in systems reflected some reality independent of the particular instant. Libchaber embraced Plato’s sense that hidden forms fill the universe. ‘But you know they do! You have seen leaves. When you look at all the leaves, aren’t you struck by the fact that the number of shapes is limited?’

Narrative construction empowers each song to have a unique “shape,” much as riffs have shapes based on the phrase they repeat and the different tonal directions it takes. Heavy metal creates a type of mental symbol in each song such that it evokes a sense not just of the immediate but of the timeless archetypes of human life. Lyrics underscore this by avoiding the personal and sensual that rock music favors, and instead looking at life through a lens of mythology, history and fantasy. If a source of modern myth exists, it might be found in heavy metal, where not only words and images but also the shape of riff and song like sigils encode a type of not universal but particular experience that resonates with all who have undergone it and amplifies context from the immediate to the eternal. In this heavy metal also resembles Greek tragedy and other types of drama in which music plays a central role.