Arthur Schopenhauer once wrote that there were three kinds of authors: those who write without thinking, those who think as they write, and those who write only because they have thought something and wish to pass it along.

Arthur Schopenhauer once wrote that there were three kinds of authors: those who write without thinking, those who think as they write, and those who write only because they have thought something and wish to pass it along.

Similarly, it is not hard to produce a decent heavy metal album. You cannot do it without thinking, but if you think while you go, you can stitch those riffs together and make a plausible effort that will delight the squealing masses.

But to produce an excellent heavy metal album is a great challenge. It’s also difficult to discuss, since if you ask 100 hessians for their list of excellent metal albums, you may well get 101 different answers. Still, all of us acknowledge that some albums rise above the rest.

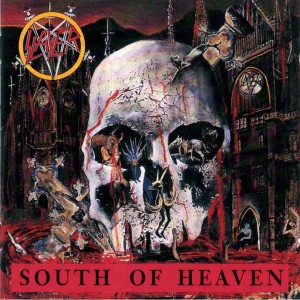

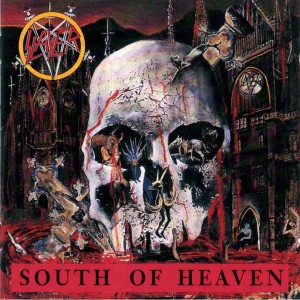

South of Heaven is to my mind such an album because it hits on all levels. Crushing riffs: check. Intense abstract structures: check. Overall feeling of darkness, power, evil, foreboding and all the things forbidden in daylight society: check. But also: a pure enigmatic sublime sense of purpose, of an order beneath the skin of things, resulting in a mind-blowing expansion of perspective? That, too.

Slayer knew they’d hit the ball out of the park with Reign in Blood. That album single-handedly defined what the next generations of metal would shoot for. It also defined for many of us the high-water mark for metal, aesthetically. Any album that wanted to be metal should shoot for the same intensity of “Angel of Death” or “Raining Blood.” It forever raised the bar in terms of technique and overall impact. Music could never back down from that peak.

However, the fertile minds in Slayer did not want to imitate themselves and repeat the past. Instead, they wanted to find out what came next. The answer was to add depth to the intensity: to add melody — the holy grail of metal has since been how to make something with the intensity of Reign in Blood but the melodic power of Don’t Break the Oath — and flesh out the sound, to use more variation in tempo, to add depth of subject matter and to make an album that was more mystical than mechanical.

Only two years later, South of Heaven did exactly that. Many fans thought they wanted Reign in Blood: The Sequel (Return to the Angel of Death) but found out that actually, they liked the change. Where Reign in Blood was an unrelenting assault by enraged demons, South of Heaven was the dark forces who infiltrated your neighborhood at night, and in the morning looked just like everyone else. It was an album that found horror lurking behind normalcy, twisted sadistic power games behind politics, and the sense of a society not off course just in politics, economics, etc. but having gone down a bad path. Having sold it soul to Satan, in other words.

The depth of despair and foreboding terror found in this album was probably more than most of us could handle at the time. 1988 was after all the peak of the Cold War, shortly before the other side collapsed, but Slayer wasn’t talking about the Cold War. For them, the problem was deeper; it was within, and it resulted from our acceptance of some kind of illusion as a force of good, when really it concealed the lurking face of evil. This gave the album a depth and terror that none have touched since. It is wholly unsettling.

Musically, advancements came aplenty. Slayer detached themselves from the rock formula entirely, using chromatic riffs to great effectiveness and relegating key changes to a mode of layering riffs. Although it was simpler and more repetitive, South of Heaven was also more hypnotic as it merged subliminal rhythms with melodies that sounded like fragments of the past. The result was more like atmospheric or ambient music, and it swallowed up the listener and brought them into an entirely different world.

South of Heaven was also the last “mythological” album from Slayer. Following the example of Black Sabbath’s “War Pigs,” Slayer’s previous lyrics found metaphysical and occult reasons for humanity’s failures, but never let us off the hook. Bad decisions beget bad results in the Slayer worldview, and those who are happiest with it are the forces of evil who mislead us and enjoy our folly, as in “Satan laughing spreads his wings” or even “Satan laughs as you eternally rot.” The lyrics to “South of Heaven” could have come from the book of Revelations, with their portrayal of a culture and society given to lusts and wickedness, collapsing from within. (Three years later, Bathory made the Wagnerian counterpoint to this with “Twilight of the Gods.” Read the two lyrics together — it’s quite influential.)

Most of all, South of Heaven was a step forward as momentous as Reign in Blood for all future metal. We can create raw intensity, it said, but we need also to find heaviness in the implications of things. In the actions we take and their certain results. In the results of a lack of attention to even simple things, like where we throw our trash and how honest we are with each other. That is a message so profoundly subversive and all-encompassing that it is terrifying. Basically, you are never off the hook; you are always on watch, because your future depends on it.

Slayer awoke in many of us a sense beyond the immediate. We were accustomed to songs that told us about personal struggles, desires and goals. But what about looking at life through the lens of history? Or even the qualitative implications of our acts? Like Romantic poetry, Slayer was a looking glass into the ancient ruins of Greece and Rome, onto the battlefields of Verdun and Stalingrad, and even more, into our own souls. Reign in Blood broke popular music free from its sense of being “protest music” or “individualistic” and showed us a wider world. South of Heaven showed us we are the decisionmakers of this world, and without our constant attention, it will burn like hell itself.

I remember from back in the day how many of my friends were afraid of South of Heaven. The first two Slayer albums could be fun; Reign in Blood was just pure intensity; South of Heaven was awake at 3 a.m. and existentially confused, fearing death and insignificance, Nietzschean “fear and trembling” style music. It unnerved me then and it does still today, but I believe every note of it is an accurate reflection of reality, and of the charge to us to make right decisions instead of convenient ones. And now with Slayer gone, we have to compel ourselves to walk this path — alone.

13 CommentsTags: goat, slayer, south of heaven