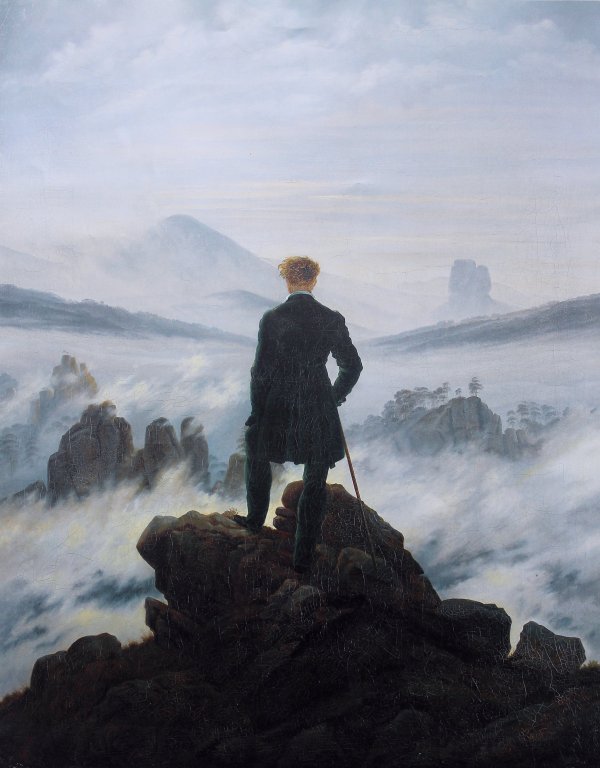

For over twenty years, this site and its predecessors have advanced the idea that heavy metal bears much in common thematically with the Romantic movement in literature, arts and music. Multiple parallels exist between what metal idealizes, and what the Romantics did.

Consider one of the better summaries of Romantic philosophy available:

Romanticism can be seen as a rejection of the precepts of order, calm, harmony, balance, idealization, and rationality that typified Classicism in general and late 18th-century Neoclassicism in particular. It was also to some extent a reaction against the Enlightenment and against 18th-century rationalism and physical materialism in general. Romanticism emphasized the individual, the subjective, the irrational, the imaginative, the personal, the spontaneous, the emotional, the visionary, and the transcendental.

Among the characteristic attitudes of Romanticism were the following: a deepened appreciation of the beauties of nature; a general exaltation of emotion over reason and of the senses over intellect; a turning in upon the self and a heightened examination of human personality and its moods and mental potentialities; a preoccupation with the genius, the hero, and the exceptional figure in general, and a focus on his passions and inner struggles; a new view of the artist as a supremely individual creator, whose creative spirit is more important than strict adherence to formal rules and traditional procedures; an emphasis upon imagination as a gateway to transcendent experience and spiritual truth; an obsessive interest in folk culture, national and ethnic cultural origins, and the medieval era; and a predilection for the exotic, the remote, the mysterious, the weird, the occult, the monstrous, the diseased, and even the satanic.

Let us put those attributes in simplified form:

- Naturalism

- Anti-rationalism

- Introspection

- Elitism

- Anti-formalism

- Transcendentalism

- Nationalism

- Occultism

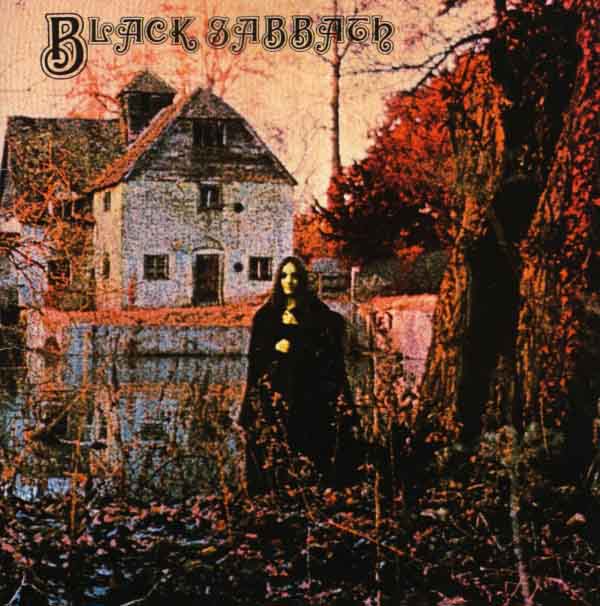

At this point, the argument makes itself, because metal frequently exhibits all of these. Naturalism manifests itself along with introspection, or a reliance on the beast within over the reasoning that becomes external when codified. Anti-rationalism and anti-formalism become a similar crossover, with a distrust of justification, rules, laws, public morals and arbitrary versions of abstract theory. Elitism is apparent both in metal’s innate hierarchy, manifested in both its quest for the hardest and heaviest music possible, and the tiered layers of importance signaled through what band is on a metalhead’s t-shirt. Occultism has been with metal from its early days, both through the horror movie and religion-inspired metaphysical explorations of Black Sabbath and the creation of epic, Tolkien-style spiritual mythology from Slayer through black metal.

Finally, we come to nationalism, which proves a troubling subject because of the ghost of Adolf Hitler which seems to loom large over all modern endeavors. While the National Socialists were nationalists (nationalism + socialism = national socialism), they were not alone in this, nor was their interpretation universal. Most saw nationalism as a glorification of national culture and a reason to turn away foreigners and not genocide them, although the numerous black and death metal lyrics about mass killing and WWII confuse the issue. Clearly Slayer were not pro-Nazi as their pejorative lyrics to “Angel of Death” illustrate, and while much of black metal — Burzum, Darkthrone, Graveland, and Emperor among others — endorsed outright national socialism, most bands took a more traditional nationalist path through pride in their identity and by reflex action, the rejection of anything which would dilute it. As the multicultural states of the West roil themselves yet again with ethnic unrest, we have to wonder if the “middle path” of Immortal, Mayhem, Enslaved and Storm might not have been a better one.

Yet nationalism is only one part of the bigger picture, although an inseparable one. People who favor a surface reading of history tend to opine that nationalism only occurred with the Enlightenment, confusing the formation of nation-states with the existence of nations, which are in fact the opposite of nation-states. A nation-state defines itself politically; a nation, both ethnically and culturally. Where the Nazis believed they could define a nation via a state with an exclusive ethnic delineation — although they had no problem admitting those who were mixed, and consequently 150,000 soldiers of mixed-Jewish heritage fought for Hitler — the Romantic-era nationalists tended to be more like Elias Lönnrot in focusing on a positive method of unification by strengthening culture against the dual onslaught of the Enlightement and the Industrial Revolution. In black metal, the form of elitism known as misanthropy crosses over with this nationalism, which seems it could be summarized as preserving the best of an ethnic group and killing off the cultureless, valueless, soft-handed beta cuck city dwellers who litter the countryside when on vacation and do nothing of value in their cubicle jobs.

The important point about Romanticism as noted above is that it rejected the Enlightenment. That dogma held that the human being itself was the highest good; Romanticism held that specific human beings, denoted by their ability to have specific thought process and mental abilities, was the highest form. Where the Enlightenment mandated a mob, the Romanticists demanded a hierarchy of realists (introspection leads to “know thyself” and thus a better understanding of reality itself). This puts Romanticism in perpetual clash with the dominant paradigm of our time, even if it is also popular with silly people who want to pretend to be deep for a few years from high school until their second job. We might distinguish between actual Romanticism and theater department Romanticism, or even “#yolo Romanticism,” which comprises the latter category.

Where do we see Romanticism in metal? First and foremost, in topic: metal bands tend to visualize life as a conflict between a thoughtless herd and a few realists who bring the heavy reality. It also shows up in the lyrics frequently, although not as clearly as in Romantic poetry. But let us begin our exploration of Romanticism with one of those classics, albeit a very popular one:

The world is too much with us; late and soon,

Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers;

Little we see in Nature that is ours;

We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!

This Sea that bares her bosom to the moon,

The winds that will be howling at all hours,

And are up-gathered now like sleeping flowers,

For this, for everything, we are out of tune;

It moves us not.–Great God! I’d rather be

A Pagan suckled in a creed outworn;

So might I, standing on this pleasant lea,

Have glimpses that would make me less forlorn;

Have sight of Proteus rising from the sea;

Or hear old Triton blow his wreathed horn.

– The World is Too Much With Us, William Wordsworth (1789)

From that we venture to a rather Romantic composition by Black Sabbath which seems out of place considering the stereotype of metal lyrics. Its poetic imagery is nearly pastoral, but still incorporates at least some of the rage of nature (“red sun” & cockerels cry”).

Red sun rising in the sky

Sleeping village, cockerels cry

Soft breeze blowing in the trees

Peace of mind, feel at ease

– Black Sabbath, “Sleeping Village,” Black Sabbath (1970)

Then, for a mixed Enlightenment/Romanticism approach, there is this rather defiant piece by Metallica which takes teenage resentment of incompetent adulthood and a one-size-fits-all egalitarian and utilitarian society and channels that anger into a statement of defiance based in the individual, but reasoning from objective problems with society at large:

Rape my mind and destroy my feelings

Don’t tell my what to do

I don’t care now, ’cause I’m on my side

And I can see through you

Feed my brain with your so called standards

Who says that I ain’t right

Break away from your common fashion

See through your blurry sightOut of my own, out to be free

One with my mind, they just can’t see

No need to hear things that they say

Life is for my own to live my own way

– Metallica, “Escape,” Ride the Lightning (1984)

Slayer took this general approach and converted it into a mythology that was as much Christian — avoidance of Satan, and fascination with the mythos of The Fall — as it was occult, incorporating elements of both alongside some defiant egotism. In this piece, the individual declares himself the opposition of all that is approved of (symbolized by “God” and “lie”) and takes on a mystical, spectral and vengeful presence:

Screams and nightmares

Of a life I want

Can’t see living this lie no

A world I haunt

You’ve lost all control of my

Heart and soul

Satan holds my future

Watch it unfoldI am the Antichrist

It’s what I was meant to be

Your God left me behind

And set my soul to be free

– Slayer, “The Antichrist,” Show No Mercy (1983)

Perhaps the most evocative lyric to my mind, and recalling scenes from another southern writer, William Faulkner, the Texas thrash band Dirty Rotten Imbeciles (DRI) wrote this paean to resistance to modern society on the basis of its ugliness and numbness. Again, the utilitarian — a culmination of Enlightenment thought — shows itself to be the enemy of the individual, but the individual points to larger things of importance (nature, beauty) as the reason for his enmity:

They block out the landscape with giant signs

Covered with pretty girls and catchy lines

Put up fences and cement the ground

To dull my senses, keep the flowers down

– Dirty Rotten Imbeciles (D.R.I.), “Give My Taxes,” Dealing With It (1985)

Finally, we come to a more stylized statement of the Slayer/DRI approach, in which the individual has like Friedrich Nietzsche rejected the definition of “good” used by the dying civilization. Instead, he is the enemy of humankind for having “(mis)understood” “this romantic place.” The usage of “romantic” here clearly refers to Romantic, and not lowercase-r romantic as in the rather icky novels with Thomas Kinkade covers. Much like Zarathustra, this individual rejects love (“hateful”) and civilization itself (“savages”) with a form of evil that originates in nature versus human delusion. Its call to destroy the excess of society and replace it with woods evokes the elitism and misanthropy of black metal, in that it sees most humans as “talking monkeys with car keys” (Kam Lee, Massacre).

Hateful savages, strong black minds

Out of the forest, kill the human kind

Burn the settlements and grow the woods

Until this romantic place is understood!

– Absurd, “Green Heart,” Raubritter/Grimmige Volksmusik (2007)

Perhaps this subject will receive future study instead of the rather politically-inclined pieces about race and gender in metal, neither of which seem to matter to metalheads except at the level of the political. Men and women of all races and creeds happily mix at metal shows, completely disagreeing with each other but, because they see civilization as failed, realizing they are not defending a social order but maintaining their own separate ones. This Romantic view sees the modern state as a parasite and modern society as a corrupt bourgeois entity dedicated to its own pleasure and wealth at the expense of shared good things like woods and truth. With that outlook, almost every metalhead can agree at least.

21 CommentsTags: Black Metal, death metal, Heavy Metal, proto-metal, Romanticism, Speed Metal, talking monkeys with car keys, the enlightenment, Thrash

As if poisonous arachnoids had woven a sticky web around a hermit of the desolate Pampas, the multitude of savage Angelcorpsean riffs blasts from Desecration Rites’ rehearsal room with hardly any control or structure for the confounded listener to immerse in. The Argentinian blackened death duo did not have the time to execute all matters properly here because of unfortunate circumstances, and it shows in the deprecated, spastic rhythm of machine, the hysterical frequency and bouts of unclean guitar work all over the place. If something is keeping these dogs of sequences under leash, it is the deep, rumbling voice of Wolf intoning Faustian misery from the bottomless depths of darkness, occasionally unwinding power lines of similar effect to Craig Pillard’s majestic demon voice in the eternally classic Onward to Golgotha. For the modern death metal fan expecting a digitized, synthetic robot surgery there is probably no more horrific sight than this deluge of an album, but internally it is far more hypnotic, intricate and deadly than one could hope for. Just listen to the freezing pseudo-Nordic moments of “Death Sentence to an Agonizing World” or the ethereal, solar and jarring interlude of “Carnal Dictum” and you might just get a slight moment of hope in the future generations after all.

As if poisonous arachnoids had woven a sticky web around a hermit of the desolate Pampas, the multitude of savage Angelcorpsean riffs blasts from Desecration Rites’ rehearsal room with hardly any control or structure for the confounded listener to immerse in. The Argentinian blackened death duo did not have the time to execute all matters properly here because of unfortunate circumstances, and it shows in the deprecated, spastic rhythm of machine, the hysterical frequency and bouts of unclean guitar work all over the place. If something is keeping these dogs of sequences under leash, it is the deep, rumbling voice of Wolf intoning Faustian misery from the bottomless depths of darkness, occasionally unwinding power lines of similar effect to Craig Pillard’s majestic demon voice in the eternally classic Onward to Golgotha. For the modern death metal fan expecting a digitized, synthetic robot surgery there is probably no more horrific sight than this deluge of an album, but internally it is far more hypnotic, intricate and deadly than one could hope for. Just listen to the freezing pseudo-Nordic moments of “Death Sentence to an Agonizing World” or the ethereal, solar and jarring interlude of “Carnal Dictum” and you might just get a slight moment of hope in the future generations after all. This British debutant lets loose the heathen wolves of war with a triumphant fanfare akin to Vlad Tepes’ famous Wladimir’s March before leading us to a journey of mountainous black metal landscapes, Graveland-esque meditations, ancient English fire-lit caves and Zoroastrian philosophy. The same sort of extended pagan tremolo epics (18 minutes of length at worst) that made countrymen Forefather and Wodensthrone veritable trials to sit through are pretty close at hand here, but the sparkling energy of youth helps a lot; there is a wildness and intrigue that contributes variation in sense even when there is none in content. Much of the logic of the songs seems to be emotionally stringing disparate sequences into a journey or a fictional narrative, which is essentially never a bad choice but some of the material here could be cut off to be brutally honest. Sound quality is the pseudo-spatial vacuum of too much reverb common for demo-level bands, but the instruments are clearly audible and the mid-rangeness is efficaceous. Unmoving and halfhearted chants and throwaway happy riffs are the blight of heathen metal, but Lord Revenant possesses sufficient pathos to allude to traces of occult evil and memories of ancient war at the same time; while this effort is not enough to coin him as a master of British metal, it would be a disappointment to hear these same songs performed by a more professional, disinterested voice in the future, or see him disappear without a trace after such a promising start.

This British debutant lets loose the heathen wolves of war with a triumphant fanfare akin to Vlad Tepes’ famous Wladimir’s March before leading us to a journey of mountainous black metal landscapes, Graveland-esque meditations, ancient English fire-lit caves and Zoroastrian philosophy. The same sort of extended pagan tremolo epics (18 minutes of length at worst) that made countrymen Forefather and Wodensthrone veritable trials to sit through are pretty close at hand here, but the sparkling energy of youth helps a lot; there is a wildness and intrigue that contributes variation in sense even when there is none in content. Much of the logic of the songs seems to be emotionally stringing disparate sequences into a journey or a fictional narrative, which is essentially never a bad choice but some of the material here could be cut off to be brutally honest. Sound quality is the pseudo-spatial vacuum of too much reverb common for demo-level bands, but the instruments are clearly audible and the mid-rangeness is efficaceous. Unmoving and halfhearted chants and throwaway happy riffs are the blight of heathen metal, but Lord Revenant possesses sufficient pathos to allude to traces of occult evil and memories of ancient war at the same time; while this effort is not enough to coin him as a master of British metal, it would be a disappointment to hear these same songs performed by a more professional, disinterested voice in the future, or see him disappear without a trace after such a promising start. More than one and a half hours of harsh, pummelling death metal is neither a mean feat to compose nor to listen. As if Wagner, Brahms or even Stravinskij decided in the otherworld that these wimpy rock/metal kids have had it too easy and possessed various souls to spend hundreds of nights writing progressive Romantic/Faustian death metal partitures, 20+ minute pieces such as the title track or “On the Throne’s Heavenward” lumber and crush with such interminable weight that it is hard to not feel like attacked by a divine hammer from above as designed by Gustave Doré. You can forget about them mosh parts, since this is material about as brainy as anything by Atheist, with slow-moving adagios and creeping crescendos more familiar from Brian Eno’s ambient music or Esoteric’s hypno-doom than anything in satanic metal realm. Vocals are sparse and it feels like about a half of the album is purely instrumental and this creates a strange calm suspension which might even feel uncomfortable; but compared to The Chasm’s mastery of technique, it still does feel like an essential emotional counterpoint or rhythmic pulse bestowing element is missing, and when the cruel vocals suddenly rip the air, it might even be perceived as a disturbance to the solemn atmosphere. Nevertheless, it is probable that they are going for exactly this synthesis of the intellectual and the primal; the emotional and the physical. So fortress-like, rational, calm and measured that it is hard to connect its spirituality with its death metal origins (even the previous Into Oblivion release), it is certainly an important statement while the cumbersome nature and certain academicism in construction (perhaps “filler” in metal language, the problem of the previous album as well) makes it a bit of an unlikely candidate for casual listening. Anyone interested in the future of Death Metal cannot afford to miss it, though.

More than one and a half hours of harsh, pummelling death metal is neither a mean feat to compose nor to listen. As if Wagner, Brahms or even Stravinskij decided in the otherworld that these wimpy rock/metal kids have had it too easy and possessed various souls to spend hundreds of nights writing progressive Romantic/Faustian death metal partitures, 20+ minute pieces such as the title track or “On the Throne’s Heavenward” lumber and crush with such interminable weight that it is hard to not feel like attacked by a divine hammer from above as designed by Gustave Doré. You can forget about them mosh parts, since this is material about as brainy as anything by Atheist, with slow-moving adagios and creeping crescendos more familiar from Brian Eno’s ambient music or Esoteric’s hypno-doom than anything in satanic metal realm. Vocals are sparse and it feels like about a half of the album is purely instrumental and this creates a strange calm suspension which might even feel uncomfortable; but compared to The Chasm’s mastery of technique, it still does feel like an essential emotional counterpoint or rhythmic pulse bestowing element is missing, and when the cruel vocals suddenly rip the air, it might even be perceived as a disturbance to the solemn atmosphere. Nevertheless, it is probable that they are going for exactly this synthesis of the intellectual and the primal; the emotional and the physical. So fortress-like, rational, calm and measured that it is hard to connect its spirituality with its death metal origins (even the previous Into Oblivion release), it is certainly an important statement while the cumbersome nature and certain academicism in construction (perhaps “filler” in metal language, the problem of the previous album as well) makes it a bit of an unlikely candidate for casual listening. Anyone interested in the future of Death Metal cannot afford to miss it, though. Heirs to the bludgeoning power of Escabios and other ancient compatriots, this recent Argentinian sect wastes no time with progressive anthems, intros nor filler in this concise EP of Autopsy influenced memoirs of early 90’s scathing death metal savagery. If the band has capacity for a challenging composition or a range of emotion, it’s all but hidden in this conflict of vulgar and intense demo taped riffs that could originate on any scummy cassette dug up from your older brother’s cardboard box vaults. Even most crustcore bands could hardly resist the temptation to fill the gaps out with something more liberal, but I am glad Bloodfiend do not resort to any loose pauses in their old school attack. The band is not yet quite there in the top ranks of death metal resurgence, but possess more than their share of contagious energy that will make for a good live experience and raise hopes for a more dynamic album.

Heirs to the bludgeoning power of Escabios and other ancient compatriots, this recent Argentinian sect wastes no time with progressive anthems, intros nor filler in this concise EP of Autopsy influenced memoirs of early 90’s scathing death metal savagery. If the band has capacity for a challenging composition or a range of emotion, it’s all but hidden in this conflict of vulgar and intense demo taped riffs that could originate on any scummy cassette dug up from your older brother’s cardboard box vaults. Even most crustcore bands could hardly resist the temptation to fill the gaps out with something more liberal, but I am glad Bloodfiend do not resort to any loose pauses in their old school attack. The band is not yet quite there in the top ranks of death metal resurgence, but possess more than their share of contagious energy that will make for a good live experience and raise hopes for a more dynamic album. Brutal death metal cliches abound but also tasteful dashes of improvisational riff integration as California youth Exylum strike from the bottomless depths with a manifest of fragmented ideas like old Cannibal Corpse, Finnish death metal and newer black metal in a blender. Weird effected voices cackle, pinch harmonics abound, chugging is all but industrial metal, drumming provides a solid backbone and the ululation of the lead guitar harmonic reaches a hysterical plane of existence when the band lets go of identity expectations and go ballistic as in the end of “Worshiping the Flesh Eating Flies”. The worst thing on this demo is the tendency to fill space with something simple and stupid like the endless low tuned one note rhythmic hammering towards the end of the title track. When the band is in a more chaotic mode, as in the older recording “Ritual Crucifixion”, the confusion serves to imbue the composition with more blood and action.

Brutal death metal cliches abound but also tasteful dashes of improvisational riff integration as California youth Exylum strike from the bottomless depths with a manifest of fragmented ideas like old Cannibal Corpse, Finnish death metal and newer black metal in a blender. Weird effected voices cackle, pinch harmonics abound, chugging is all but industrial metal, drumming provides a solid backbone and the ululation of the lead guitar harmonic reaches a hysterical plane of existence when the band lets go of identity expectations and go ballistic as in the end of “Worshiping the Flesh Eating Flies”. The worst thing on this demo is the tendency to fill space with something simple and stupid like the endless low tuned one note rhythmic hammering towards the end of the title track. When the band is in a more chaotic mode, as in the older recording “Ritual Crucifixion”, the confusion serves to imbue the composition with more blood and action. As persistence is the key to cosmic victory, it’s gratifying to see that this recent Californian cluster is not giving up in their quest to build a maiming death metal experience which was approached with streamlined Bolt Thrower and Cannibal Corpse tendencies in their last year’s EP. First threatening edges noted by the listener here are their improved musicianship with plenty of rhythmically aware palm-muting and tremolo NY style rhythm guitar riffs interlocking like the paths of ferocious large insects on flight while in the new drummer Kendric DiStefano they have a redeemer from the abhorrent pit of drum machine grind, even though his style tends to approach the robotic at times. The moments where this EP shines is when the brutal backbone operates at the behest of melody conjured by the leads of Mike Flory and Daniel Austi, such as the gripping mid-section of “Exit Wounds” and the Nile-ish mad arab string conjuration in “Litany of Blood”. I’m still reluctant to call this a total winner because there’s a lot of random chugging around as in generic bands from Six Feet Under to Hypocrisy, but there are also subtle technical flourishes such as the lightly arpeggiated bridge in “War Machine” that still keeps me liking this band and following its movements.

As persistence is the key to cosmic victory, it’s gratifying to see that this recent Californian cluster is not giving up in their quest to build a maiming death metal experience which was approached with streamlined Bolt Thrower and Cannibal Corpse tendencies in their last year’s EP. First threatening edges noted by the listener here are their improved musicianship with plenty of rhythmically aware palm-muting and tremolo NY style rhythm guitar riffs interlocking like the paths of ferocious large insects on flight while in the new drummer Kendric DiStefano they have a redeemer from the abhorrent pit of drum machine grind, even though his style tends to approach the robotic at times. The moments where this EP shines is when the brutal backbone operates at the behest of melody conjured by the leads of Mike Flory and Daniel Austi, such as the gripping mid-section of “Exit Wounds” and the Nile-ish mad arab string conjuration in “Litany of Blood”. I’m still reluctant to call this a total winner because there’s a lot of random chugging around as in generic bands from Six Feet Under to Hypocrisy, but there are also subtle technical flourishes such as the lightly arpeggiated bridge in “War Machine” that still keeps me liking this band and following its movements.