As author of The Heavy Metal FAQ, I have wrestled with the question of how to define metal over the years. Since it uses the same techniques as any other form of music, but used in different proportions and combinations, I have always focused on the idea that unites these uses which makes metal so obviously distinct from rock, punk and other forms of music.

To this I’d like to add another idea: metal is not literal. That is, metal tends to view the world through a symbolic or mythological lens. It does so to reflect our inward sensations about what is going on, plus a historical viewpoint which requires a more high-level view. The details don’t matter as much as the form, in metal, and we pay attention to the form and then put it in a folk-wisdom format.

Archetypal examples of this can be found in classic metal like “War Pigs” (Black Sabbath), “Hardening of the Arteries” (Slayer), “Painkiller” (Judas Priest) and “My Journey to the Stars” (Burzum). In these songs, mythological forces clash to reveal a truth of everyday life. They inform us about our time and put us into a symbolic and emotional framework with it in which we want to fight it out, fix it, struggle and win.

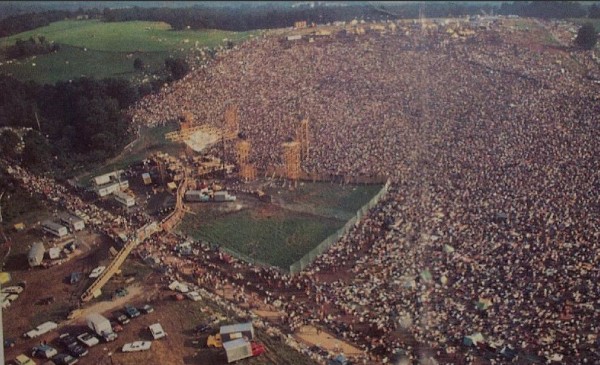

In contrast, most music is either sensuality-based or protest music. Sensuality-based music is exemplified by stuff like Shakira. Protest music really exploded in the 1960s, but reformed itself with punk, which took a more abstract and yet earthy view. Where the 60s bands sang about politics, punks sang about everyday life and the insanity of existence. This finally culminated in thrash, which used hints of metal’s mythology to make the personal into the universal, as in “Give My Taxes Back” (DRI), “M.A.D.” (Cryptic Slaughter), “Minds are Controlled” (COC) and “Man Unkind” (DRI).

Metal does go wrong sometimes and get literal. The worst of these are the ego-based songs, as in Pantera, or the songs about being metal and going to shows and the like, which are generally just dumb. It is not surprising that these are not favorites of the genre because they drop away from that 30,000-foot view and instead become more personal drama like the rest of our society, which explains why its institutions don’t function and its ideas are corrupt.

Interestingly, other genres are not literal either. Progressive rock was famous for songs about weird adventures in fantasy worlds that had striking parallels to our own (compare to JRR Tolkien and CS Lewis). Classical music tends toward fantastic descriptions from literature and history. These are genres of the weighty and impersonal, not the direct and immediate and personal. They have a different scope and internal language.

Jazz is the outlier. When sung, it tends toward protest and sensual lyrics. When instrumental, the sound of it suggests a combination of the two: a kind of secular (no meaning greater than the material and immediate) version of imagination, but applied to literal experience, such that it forms a kind of texture without a unifying core. It communicates the loneliness of modern isolation and a retreat into the personal complexity of the mind.

Where metal stands out among modern genres is that it still embraces this viewpoint, or at least did until the nu/mod-metal started appearing. Part of what makes such a viewpoint necessary is that metal, despite being about killer riffs, is not about the riff. It’s about many riffs stitched together to make an experience so that when the killer riff comes out, it has a meaning in context that makes it heavy. No song is heavy from just one riff. It’s heavy because when you get to that super-heavy riff, everything else has set it up to resonate.

This in part explains the audience of metal. Mythology, historical significance and topics of philosophy do not inspire the honor students, who are busy working on their careers (and the obedience-profitability nexus that these entail), or the average student, who is busy in a world of his/her own pleasures and delights. They do however appeal to the outliers, the dreamers and dissidents, who might find class boring because they find society boring and purposeless, and instead turn toward fantasy and a bigger, more abstract realism to express themselves.

13 CommentsTags: classical music, Hardcore Punk, Heavy Metal, jazz, literality, mythic imagination, Mythology, progressive rock, protest rock, punk, punk rock, rock 'n' roll