As part of our exploration of the ideas behind the metal, we take frequent peeks into the world of academia, where a number of metal academics are writing, teaching and evangelizing heavy metal as a cultural and artistic force. This is one mechanism for metal to rise above mere “product” status and be understood as a phenomenon with something to contribute to our understanding and society at large.

Today we chat with metal professor John Sewell, author of “Doing it For The Dudes”: A Comparative Ethnographic Study of Performative Masculinity in Heavy Metal and Hardcore Subcultures and the University of West Georgia’s resident metal analyst. We’re grateful to him for sparing us the time to chat about the meaning behind metal, and what it is that makes this genre quite difficult to pin down.

How did you become an academic? Was this something that you aspired to your whole life?

The academic thing kind of happened by accident. I wanted to be a musician — and I kind of was. For around 20 years I played in bands while supporting myself as a pizza delivery guy and, after finishing my BS in Journalism in 1997, a freelance writer for alternative newspapers. Most of my bands did OK, meaning that I toured a good bit, played on several independent releases, and had a little bit of regional notoriety. But I (finally) had my midlife crisis and accepted that music wasn’t going to happen for me. I enrolled in a Master’s program in Journalism, mainly because I didn’t know what else to do with myself at the time. And then it got interesting.

Do you identify as a metalhead? Or maybe I should ask: is there a pattern of metal music listening in your past?

I have always listened to metal, but I consider myself more of a punk rocker who loves metal than a metalhead per se. In the early 80s I discovered Venom and Motorhead, and then the metal/hardcore crossover thing. I especially loved Black Flag, who had a definite metal influence on their later albums. I listened to a lot of metal in the 80s and 90s, but it was kind of an addendum to the punk and hardcore music I really loved. During that period the metal bands were really macho and seemed too focused on getting mainstream success, which turned me off. But metal has always been an important part of my musical menu.

In 2006 I moved to Atlanta to be in Georgia State University’s Ph.D. program in Public Communication. I’ve always gone to a lot of shows, and Atlanta’s metal scene is huge, and there are tons of excellent bands right now. So I ended up going to a lot of metal shows and really digging it. By this time, metal, hardcore and punk had kind of morphed into this big ugly thing that I loved. I found myself being able to relate to the metal crowd better. The metal shows gave that unified-yet-dangerous feeling I used to get at punk and hardcore shows. Seeing these bands live made it click for me. Metal is best appreciated at shows. I’d see these crazy-ass, discordant bands I’d go home and listen to the music on my own. The noisy, extreme stuff started sounding more like music to me.

What do you find interesting about metal, both (a) individually and (b) as a research topic?

Metal is interesting because it’s never going to go away. Metal has the most ardent fans of any rock music subgenre. What’s really interesting is that metal has become more underground instead of being absorbed into the mainstream. In this way, metal subculture has had kind of a backwards progression. Diehard metal fans know their music isn’t going to get wildly popular and their scene isn’t going to be coopted per se. The bands just get more extreme and the scene gets more alienated from the mainstream. It’s perfect.

Metal is interesting as a research topic because there’s all this crazy stuff going on. Metal is not just music, it’s a collective identity. And this identity has a lot of implications about power, race, class, gender and sexuality. There’s this perception in the mainstream that metal is kind of dumb — that it’s this “trash” culture. And metalheads almost embrace this proud pariah thing. Being a metalhead might have negative impact on social mobility, but metalheads really couldn’t care less.

Your research indicates that black metal finds importance in “transgression.” What is transgression?

I’m a little bit wary of this question because I don’t want to establish some static definition. What seems transgressive for one person might seem like conformity to another. Kahn-Harris does a great job of addressing this with his concepts of transgressive and mundane subcultural capital.

Anyway, I think of transgression as purposeful refusal and/or inversion — finding beauty in ugliness, power through alienation or embracing the queer, for example.

You say that, “Black metal’s self-maintaining categorical imperative produces a constituency strictly demarcated and alienated from the mainstream” and suggest that black metal’s subcultural rules serve to further separate its members from mainstream society. Why do you think this behavior has evolved, and has it succeeded in what it was an attempt to do?

Black metal is interesting because its progenitors (well, the few surviving ones, that is) keep rewriting their histories to fit grand artistic and ideological schemes. From the onset, the early black metal guys like Dead, Euronymous and Varg Vikernes probably just wanted to make the wildest, heaviest music possible. They were kids who were playing around with dangerous stuff.

The crazy stuff like murders and church-burnings, well, that seems like adolescent one-upmanship to me — kind of a contest to see who could be the most hard and evil. But the murders and church-burnings were the grist for the hysteria, and the hysteria drew worldwide attention to what was before a sub-underground phenomenon that may well have otherwise frittered out.

Here we are over 20 years later and the progenitors (Hunt-Hendrix terms this bunch “hyperborean black metal”) are still, more or less the archetypes in terms of sound, self-presentation and at least to a degree ideology. I think USBM has backpedaled on the Norse/Aryan/Nazi stuff, which is bullshit anyway. But that ideology of transgression/refusal remains a linchpin of black metal. In this way black metal (like all other long-running subcultures) is a thing that cannot be: Can a collectivity of rebels really rebel? And if black metal’s categorical imperative is the annihilation of the self, why has it stayed around so long? “Success,” as the annihilation of the self, would have impelled an end to the subculture. And black metal is not going away.

I think the difference here (and the reason for the persistence of black metal subculture) is that we are talking about artistic and symbolic transgression — not transgression in the lived world per se. Dead and (especially) Varg Vikernes, among others, crossed the boundaries between symbolic transgression and transgression in the lived world, and ended up dead or in jail as a result. There’s not so much idiotic behavior associated with black metal today, or at least it’s not as idiotic. And so it goes.

The filmmakers of the black metal documentary “Until the Light Takes Us” refer to their film as a study in the decay of meaning. Does meaning decay? Is there any way to stop it from doing so? Does this correspond at all to the in-group behaviors you have observed?

It’s been a few years since I’ve seen the movie, and I think I should go back and watch it again. I only saw it once on cable, and I was probably playing guitar, eating dinner and working a crossword puzzle at the same time. When I saw it I thought it was pretentious and slow.

This is a tough question because I don’t know exactly what the filmmakers meant by “decay of meaning,” and I don’t know whether this decay of meaning was what they really intended to convey in the film — or if that was just a hifalutin concept to tack on in an interview.

Anyway, I don’t think meaning decays as much as it evolves. Meaning is polysemic. Meaning is relative. I think it’s most productive to look at black metal music and subculture as discourse. Meanings, within discourse, are not static.

A better way to understand black metal might be as an evolution of myth instead of as a decay of meaning. Black metal is in its way ideological, and thus subject to semiotics. Black metal subculture is — like it or not — a collective phenomenon. And subculture is the terrain upon which shared meanings are contested and policed. In black metal (or any subculture), meanings evolve through interaction. “Decay of meaning” sounds more badass, and thus more black metal. But I don’t think meaning is decaying in black metal. Meaning is actually fertile in black metal — especially the meaning of myth. And the collective negotiation of meaning in black metal is where the action is.

Further in this paper — this is Pure Fucking Armageddon — you say “Black metal atomizes the ‘I,'” — forgive me if this is redundant, but are you sure that black metal did this? Are some people so constructed that their spiritual, social, philosophical and mental needs are incompatible with our current civilization?

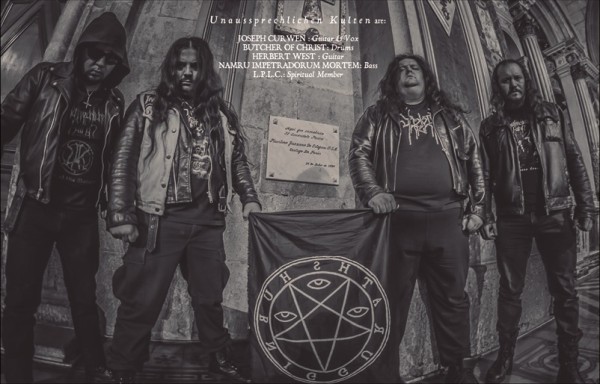

Black metal at least symbolically atomizes the “I.” And this brings us to another of black metal’s many paradoxes. Black metal’s refusal/transgression is in its way individualistic, but the identity of the individual in black metal is oftentimes atomized — or at least obfuscated. I mean, look at the interchangeability of people with corpsepaint! Look at how similar (and similarly unreadable) the band logos are! And when Joe Smith changes his name to Sardonicus, well, Joe Smith is symbolically annihilated.

Sure, some people’s spiritual, social, philosophical and mental needs are incompatible with our current civilization. This is nothing new. Subcultures are collectivities that exist within the greater culture — and these collectivities, even black metal, operate as havens for the proud pariahs. Black metal indeed fulfills spiritual and philosophical needs for the alienated — and it also offers an identity and a sense of belonging. So in some ways people actually find identity through the conduit of black metal. It’s strange.

Do you think there’s a point to academically chronicling black metal past the 1993-1994 watershed era? Is the music today even from the same genre?

This is another yes and no answer. Today’s black metal is far evolved from what Mayhem and Emperor did way back when. Personally, I don’t think the music of any of those bands associated with murders and church-burnings was that good, anyway.

Every subgenre of rock music undergoes continual redefinition. For example, today’s hardcore is nothing like what hardcore was in 1982. Today’s psychobilly is not the same as the psychobilly of 1990. And of course the same goes for black metal.

Genre classification seems a necessary evil, though. The meanings of genre and accompanying subculture classifications evolve semiotically, and today’s meanings are never exactly yesterday’s or last year’s meanings. Scholars from the symbolic interactionist camp would probably have a lot to say about this. I think that genres and subcultures should be conceptualized as continuums with permeable, ever-evolving boundaries.

Today’s music and today’s scene is not the same as, aargh, “back in the day,” but the archetypes of hyperborean black metal are still hugely influential.

You say that maintaining boundaries is a key function of subcultures. Why is this?

This questions brings me back to Kenneth Burke’s idea that identification is an act of negation. By identifying as one thing, we negate the other. By saying what we are, we are also necessarily saying what we are not. To have an insider group, you must also have an externalized other. Maintaining difference (or some might say faux individuality) is a categorical imperative of any subculture.

You also mention that the kind of acts that succeed in a subculture environment are those which set the individual apart from the herd, and include criticism of the subculture itself. Wouldn’t that make a subculture self-consuming? Are any of them post-individualist?

Subcultures are kind of things that cannot be — or at least they become things that cannot be as they balkanize. This is to say that yes, subcultures are in a way self-consuming and/or self-negating. Such subcultural self-negation is especially prevalent in rock music subcultures. For example, there are scads of scrawny male musicians with that dyed black comb-over haircut who play guitar-driven, post-pop/punk songs about longing and heartbreak and insist that they are “not emo,” when they are exactly that.

More often than not, music subcultures that purport to be individualistic are in fact post-individualistic in that the act of joining the subculture actually negates one’s individuality in a process of conforming to the norms of expression, behavior and self-presentation of that enclave.

And then there’s the black metal bunch, of which some participants claim to be post-individualist. For these folks, black metal negates the “I.” Still, this negation of the “I,” of obliterating Joe Smith’s identity in the process of becoming Sardonicus, paradoxically provides a means to set oneself apart — even sometimes operating as a portal to small scale rock stardom. Many black metal musicians decry fame and popularity — unless and until the potential for said popularity becomes a possibility, that is.

You mention another thinker (Butler) who says that black metal is comprised, to an extend unmet by other forms of music, of references to “the enduring, the abiding, and the transcendent.” Why do you think black metal values these things? Can you think of any other philosophies or belief systems that value similar ideals?

When I was a kid, KISS was my favorite band. After one of their shows, I was talking about the experience with one of my friends. He was saying that a KISS concert was like a religious revival in that it was a cathartic, theatrical experience where a group of people worked themselves into a collective frenzy, led by a charismatic leader. That was a pretty perceptive analysis for a 12 year old. It blew my mind at the time, but I knew it was true.

While black metal (as Butler contends) indeed references “the enduring, the abiding, and the transcendent” most overtly, I think it is a bit of a stretch to say that black metal is in fact more spiritually transformative than other genres. I’m sure that fans of jazz, classical music and techno, for example, would all tell you that their preferred form of music operates as a portal to other realms of consciousness — much in the same way that black metal (or football, for that matter) does for its adherents. Any form of music, any form of ritual, surely, offers an entrée into the realm of the ecstatic — for someone.

In this way, all music (black metal included) operates as a portal to the numen, the ur-mind. I daresay that all philosophies or belief systems value similar ideals. They just have different ways of getting there. Loud music is my way of getting there.

In your paper Pure Fucking Armageddon, you repeatedly refer to the black metaller as the “sin eater, a pariah who finds spiritual illumination through the excess for which he is damned.” Do you see a parallel in this to the writings of William Blake, who notably said, “The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom.” Is there some reason that all us post-moderns are trying to break through mundanity, trying to get back to the real underneath the surreal “real,” as if we trusted the “subtext” more than the “text” in our modern existence?

I’ve heard that Blake quote several times, but I’ve never actually read his work.

I also find the use of the term “real” somewhat problematic here — mainly because I’m intimidated by “real” in a Lacanian sense. I could keep reading Lacan for the rest of my life and never be exactly sure that I got it.

Anyway, I think that all forms of ritual and creative expression have always sought to break through the mundane to some degree. Baudrillard, Bakhtin, Huxley, Nietzsche and Marcuse (among countless others) have theorized this forever.

So, in a postmodern sense, one could capably argue that genres such as black metal seek to shatter the hyperreal (see Baudrillard) in an attempt to “get real,” as it were. And what could be more “real,” more shattering, more pre-cognitive, more pre and post symbolic than death itself?

In Doin’ it for the Dudes, you define heavy metal as being centered around “power.” What is this power, and why is heavy metal obsessed with it? How does this correspond to heavy metal’s fascination with all things dark and evil?

There is nothing about heavy metal that isn’t contradictory in some way, it seems. There is a lot about heavy metal that I’m uncomfortable with. There is a lot about heavy metal that is downright dumb. But the wrongness and the dumbness of heavy metal is, for me, part of its allure.

There are few, if any subtleties in heavy metal. The “power” of heavy metal is blunt force. The shows are as loud and physically punishing as possible for fans and performers alike. A metal show is something to be endured as much (or more) than enjoyed. Lyrically, metal is about war, the occult, torture, dismemberment, totalitarianism and death.

Ultimately, heavy metal is masculine power, performed by and for males.

You write about how heavy metal is hypermasculinized, yet doesn’t challenge conventional genre roles. Do you see a parallel between those two?

I’m not sure I understand this question. Why would hypermasculinity challenge conventional masculinity? I see hypermasculinity as the amplification of conventional (hegemonic, heterosexist) masculinity.

What I have found through my work is that the performative (hyper)masculinity of heavy metal bolsters the hegemonic masculinity of the culture at large in a way that, nevertheless, is not empowering for heavy metal males in an extra-subcultural sense. Heavy metal masculinity is double-edged masculinity.

Heavy metal links the performativity of masculinity with the performativity of working classness. This is to say that heavy metal males, quite often from middle or upper-class backgrounds, enact archetypes of working class masculinity. These symbolic enactments of working class masculinity by metalhead males function to render a disempowered heavy metal male subject. In other words, by participating in a proud pariah subculture that is considered by many to be “white trash” or “low” culture, heavy metal males become “white trash” or “low” culture.

Of course, it would be wrong to paint the heavy metal experience for males in a single, broad stroke. Heavy metal males also experience their subcultural participation as empowerment. They don’t care what society at large thinks of them. And if they experience participation in metal subculture as empowerment, then, for them it is empowerment. After all, however we experience something is, for us, reality.

By enacting a mutated, caveman-style masculinity that is so over the top it’s almost satirical, heavy metal males support hegemonic masculinity — which is a hierarchy of males in a heterosexist hierarchy. The male power exerted in heavy metal’s male hierarchy does not translate as power in the masculinist hierarchies of the greater culture, however. You’ll rarely see heavy metal males becoming senators or corporate CEOs.

So, in a nutshell I’m saying that heavy metal dudes, in the process of becoming heavy metal dudes, join an outsider enclave and are relegated to the fringes of society. And they celebrate this. They don’t care what people think about them, their music and their subculture.

What have been the consequences of your heavy metal research? Has it led to you being thrown out of fancy restaurants and ostracized by your peers? Or are people opening up to this art form?

I rarely go to fancy restaurants and have yet to have been thrown out of one for my metal scholarship.

That said, I do sometimes get the impression that some (by no means all) of my peers in academia think that heavy metal is not something that is really valid and that, in turn, metal studies is not a valid pursuit, either. Some folks think the academic study of metal is about as worthwhile as the academic study of professional wrestling, for example. (There are many parallels between metal and professional wrestling, by the way. And I think professional wrestling is a worthy topic for academic study as well.) I’m guessing this all somehow comes back to the distinction of “high” and “low” art.

If metal became acceptable for the mainstream, that would mean the genre had been rendered toothless. If metal didn’t offend somebody, well, it wouldn’t be metal anymore. Metal (and therefore metal studies) will probably remain to a degree relegated to the low art ghetto, and that’s just fine.

Where has your research taken you since the two papers, Pure Fucking Armageddon and Doin’ it for the Dudes, that launched your career as a heavy metal academic?

As you know, academic publishing is a painfully slow process. I submitted a couple of articles based on chapters of Doing it for The Dudes to academic journals and am waiting for the reviews. I expect that I will have at least one metal studies article published this year. I am attending the Heavy Metal Music and the Communal Experience conference in Puerto Rico this spring. I hope to make some important contacts at that event.

I don’t limit my research work to metal studies, however. All of my work somehow merges cultural studies and critical theory traditions to examine the interplay of gender, race, class and sexuality in constructed group identities. I have written an article examining the evolution of the term “queer” using Ernesto Laclau’s logic of equivalence that will be published this October. It’s a provocative piece, I think. I’m proud of that one and looking forward to seeing how that is received.

My metal studies work would be useful for anyone studying how gender is enacted as a collective identity. Likewise, my gender studies work might be useful for someone who is studying metal.

What do you think a study of heavy metal has to offer the wider society around us?

Studying heavy metal allows scholars the opportunity to examine the interconnectedness of (here we go again) gender, race, class and sexuality in a particular art form/subculture. So the study of heavy metal offers clues — on a micro level — as to how gender, race, class, sexuality and (yes) power are deployed in the whole of society.

If you are an academic with related interests to Mr. Sewell’s, he welcomes communications via email at johns@westga.edu.

16 CommentsTags: alienation, atomization, Black Metal, interview, john sewell, metal academia, negation, transgression