Old school horror books often focused on plotlines where an inner psychological trauma became manifested in a physical evil. Metaphorically, this plot generates a lot of appeal because it mimics the worst of the human condition: neurotic and blinded to our own inner corruption, we humans have a tendency to act out our psychological dysfunction on the world. The horror story takes this only one step further by mythologizing it, and putting abstract dysfunction into a visual form so we can recognize it, unlike when it remains within us.

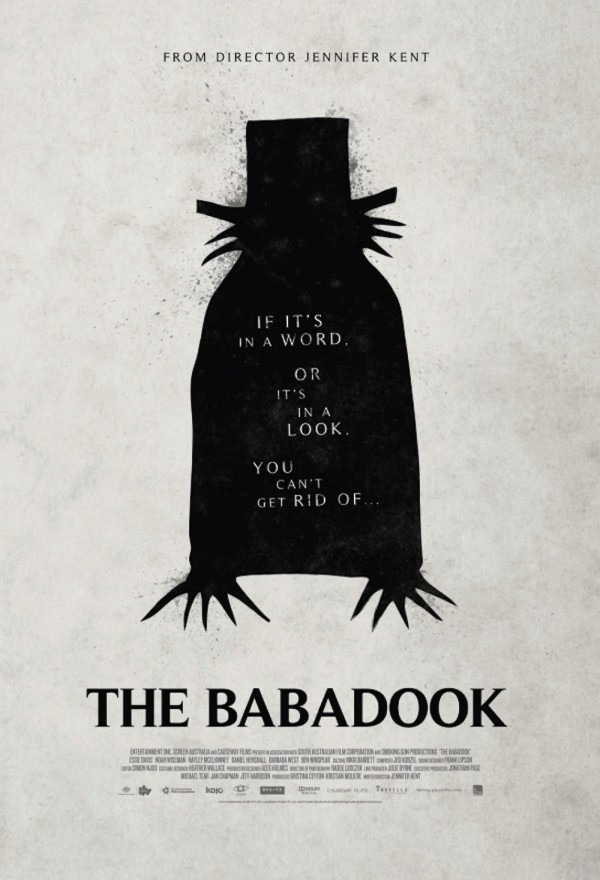

The Babadook takes on this plot family — comparable to riff archetype in metal — and makes of it a movie that is one-half tedium and one-half incoherence. It holds up the metaphor reasonably well, but loses sight of its purpose early on, and like many movies with female directors, concentrates on “atmosphere” to the point of making the audience lose sympathy for the characters. Although it brings itself full circle without pandering to the easy options for plot conclusion, such as character insanity or dream, its failure to make sense of the challenge to the main character, Amelia, renders the storyline into gibberish at the end.

The setup is simple: Amelia has a son, Samuel, who was born on the day her husband died. The husband, Oskar, was killed in a car crash on a rainy night as he drove Amelia to the hospital to birth Samuel. Seven years later, she still becomes morbid and withdrawn as the day that Samuel was born approaches. The child, on the other hand, never has a guilt-free birthday party. Working the standard pointless modern job, and struggling with her own inability to snap out of her reverie, Amelia struggles with the more profound problem of Samuel, who acts like a child with severe emotional problems. As the movie goes on, both Amelia and Samuel essentially retreat or are exiled from the world as their increasingly bizarre and dangerous behavior threatens others.

During the midst of this, Samuel finds a pop-up book that tells the story of a creature called the Babadook. The book is written in annoying sing-song rhyme, but it makes its point that is essential to the metaphor of the story: the more you deny the presence of the Babadook, the more he takes over you. The obvious analogy to grief itself, and the inability to escape or unwillingness to give up prolonged mourning, shows us the weakness in Amelia that allows evil to enter… or escape. In some of the most tired plot devices in horror, the book keeps re-appearing after being destroyed or hidden, adding new lines to the rhyme as life falls apart for Amelia and Samuel.

Like many other modern films, The Babadook features characters who are chronically sleep-deprived. This bit of realism resonates with audiences, so many of the newer generation of psychological horror films adopt it. Here it is worn to death and repeated to the point of tedium during the first half of the film. At the midpoint of the film, everyone changes roles. Samuel, the useless and destructive child, suddenly becomes responsible. Amelia suddenly spaces out and becomes useless. Unfortunately for all viewers of this film, the remaining “suspense” repeats the same three techniques very slowly so we understand the atmosphere, and as a result avoids sheer tedium but replaces it with predictability and storyline nonsense as characters undergo brain damage in order to allow the plot to stay together. That and gratuitous (and mostly ineffectual) pet death are supposed to shock us into dropping our iPhones into our arugula salad and calling our husband who are working late at their corporate jobs, in hysterics at how “shocking” it all is. Except that it is not. It is babble.

This film could have been great because the metaphor resonates with us all in this time of intense victimhood. For it to do that, however, it would have to overcome its favorable view of victimhood and get serious about its own metaphor, producing a creature that is believable which mimics grief in its ability to consume people, instead of just making them go crazy and act completely against common sense, which makes it impossible for the audience to identify with them. The plot needed a careful structuring to show the reason for the projection of grief into this creature, and then needed some kind of plot device that defeats the evil. It has neither of these. It hides behind sloppy screenwriting which it justifies with the idea that it enhances the mystery or atmosphere, but it does neither. This script is incomplete and what was there did not stretch for the full length of the film.

The Babadook falls short of not only its own potential, but the standard it would need to meet for the experienced suspense-horror audience, but could easily have achieved greatness. The acting — especially by Essie Davis as Amelia — is very well-executed. Cinematography does not strike an excessive note, nor does it stand out as particularly excellent, but it rises far above mediocre. The problem of the storyline dooms this film. “Atmosphere” serves as a cop-out for what really needed to be done: to tell the story of grief and self-pity with an unblinking eye, and by showing us that psychology as a metaphorical monster, revealing what must be done to defeat that crippling choice and sensation in ourselves.

11 CommentsTags: daniel henshall, essie davis, Horror, horror film, jennifer kent, noah wiseman, suspense

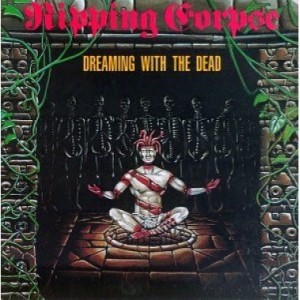

Chris Reifert is on top form as a vocalist. His ability to evoke majestic visions of dismemberment and perversion seem to contain a greater dynamic than usual, as to suggest that nearly fifteen years of prolonged absence has only allowed his strengths to re-accumulate.

Chris Reifert is on top form as a vocalist. His ability to evoke majestic visions of dismemberment and perversion seem to contain a greater dynamic than usual, as to suggest that nearly fifteen years of prolonged absence has only allowed his strengths to re-accumulate.

Although the adverse effect of retaining such past influences would be that some later songs still structure themselves around anthemic choruses – a burden that most of Ripping Corpse’s contemporaries had already evolved far beyond – the band manages to employ enough compexity in their compositions to keep up with the demands of their vision. The sound of the guitars may be construed as being weak or mixed poorly, but this lighter texture lends itself well to the progression of riffs from measured punctuations of rhythm to insane variations by way of fucked up artificial harmonics and blastbeaten tremolo sequences. Tempo blurs the lines of what is considered primitive, though the act may be embellished with the jewels of modern society or justified in the name of some ideology. As layers of humanity are removed from the conscious mind, lead guitars erratically and uncontrollably rip through passages and bring a microcosmic level of culmination within a song, like the fleeting screams of demons being exorcised from a long tortured soul.

Although the adverse effect of retaining such past influences would be that some later songs still structure themselves around anthemic choruses – a burden that most of Ripping Corpse’s contemporaries had already evolved far beyond – the band manages to employ enough compexity in their compositions to keep up with the demands of their vision. The sound of the guitars may be construed as being weak or mixed poorly, but this lighter texture lends itself well to the progression of riffs from measured punctuations of rhythm to insane variations by way of fucked up artificial harmonics and blastbeaten tremolo sequences. Tempo blurs the lines of what is considered primitive, though the act may be embellished with the jewels of modern society or justified in the name of some ideology. As layers of humanity are removed from the conscious mind, lead guitars erratically and uncontrollably rip through passages and bring a microcosmic level of culmination within a song, like the fleeting screams of demons being exorcised from a long tortured soul.