Suppose that you’re a dying society (“the human race was dying out / no one left to scream and shout” – the Doors) and that you decide to give it one last hurrah. To try honesty instead of manipulation.

Suppose that you’re a dying society (“the human race was dying out / no one left to scream and shout” – the Doors) and that you decide to give it one last hurrah. To try honesty instead of manipulation.

You might come up with punk music. It strips out everything that reeks of manipulation. The good production, gone; the complex chords, gone; any pretense of musicianship, out the window.

But then people realize that you’re going about it backward. You can’t change your methods to change your goal. You have to change your goal. That means you’re thinking about composing music in a new way, not just how you’re going to play differently with something rather familiar.

This lets loose the dogs of war.

No longer is music carved from a known pattern; the song is the pattern, and it obeys no rule other than its content. Face value is made secondary to internal value. Like it is in human, whether we have souls or not.

This is what Discharge did to the world of punk — and later, to metal:

Musically, punk’s first wave hadn’t been all that far removed from regular rock’n’roll. “God Save the Queen,” with its hummable melody and simplistic chord changes, is clearly a relation, albeit distant, of Chuck Berry and the Rolling Stones. The difference is in the attitude, in Johnny Rotten’s adenoidal snarl.

Discharge’s revamped version of punk bore little resemblance to anything that had come before. It was faster, harsher, and often almost entirely lacking in melody. The riffs were generally three-chord affairs, but they were played at warp speed, accompanied by a rumbling bass and a merciless, galloping drumbeat. The songs rarely topped the two-minute mark. As Garry Maloney, who drummed on some of the band’s best recordings, explained to a ‘zine called Trakmarx, “We just embraced speed—the concept—not the drug—took it to its logical limit.”

Away went the blues scale, playing in uniform musical measures, and having pop song format work for you. Instead, the new vision was the lawless chromatic scale, a lack of key and thus of soaring bridge and chorus, or even any fixed song format. It was repetition made into its own undoing, a type of ambient music made from noise.

Rock ‘n’ roll died with Discharge. Others, like Amebix and The Exploited, followed. On US shores the Cro-Mags and thrash (DRI, COC, Cryptic Slaughter, Dead Horse, Fearless Iranians From Hell) further put metal into punk. With metal’s phrasal riffs and punk’s lack of structure, music got closer to ancient times.

Suddenly, the melody determined the song, and since the songs were topical, the melody was determined by the idea. Like ancient Greek dramas, where the chorus sang poetry as the story was acted out on stage, the new punk-metal hybrid entered the world of motifs and mimetic meaning, where art imitates life to tell the story of a journey or adventure and how it changed those who sallied forth.

The end of the second song, nearly eight minutes in, elicited a weak cheer, a few claps, and a robust chant of “D.R.I.”—a local thrash band on the rise, which had played earlier that night.

This was the new legion, thrash and underground metal (death metal and black metal), and it ushered in a new era. Where music was plain-spoken like punk, but mythological like metal. Where it took metal’s criticism of human behavior and used that to explain punk’s extreme political dissidence. Where people started looking at what they’d die for instead of what they’d live for.

Since that time, metal and punk have both gone through many generations. None have gotten very far from those originals who broke free however. They had to destroy before they could create and, when the dust of destruction and subsequent self-destruction finally settles, creation will begin anew.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3DmSbqmJaig

3 CommentsTags: Ambient, Black Metal, death metal, discharge, Hardcore, punk

In the early 1980s, punks had a wary attitude toward metal because they saw it as commercializing their music. As I finally get around to hearing Integrity’s Those Who Fear Tomorrow, I see their point, although it’s not an important one.

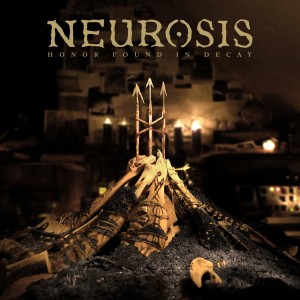

In the early 1980s, punks had a wary attitude toward metal because they saw it as commercializing their music. As I finally get around to hearing Integrity’s Those Who Fear Tomorrow, I see their point, although it’s not an important one. Neurosis got a bad rap among metalheads because most of us got introduced to this innovative band at the peak of their career, when metal journalists and radio were pushing the metalcore trend and wanted us to consider Neurosis part of that movement.

Neurosis got a bad rap among metalheads because most of us got introduced to this innovative band at the peak of their career, when metal journalists and radio were pushing the metalcore trend and wanted us to consider Neurosis part of that movement.

On first listen some would easily assume that this release were a mere product of nostalgia of underground metal of the 1980′s, at least indicated so by the production and indication that are present here. However this is death/speed/black metal firmly rooted in the underground

On first listen some would easily assume that this release were a mere product of nostalgia of underground metal of the 1980′s, at least indicated so by the production and indication that are present here. However this is death/speed/black metal firmly rooted in the underground  Coming from the anarcho-punk school of musical and ideological tradition, and finally releasing this, their debut full length in 1985, Amebix had already released a series of excellent EP’s in the early half of the decade. The unique character of their music was a sound that fused the violent hardcore punk of Discharge with the circulative, repetitious song structures that were a staple of post-punk acts such as Killing Joke and Public Image Ltd. Escaping the social-activist themes that were a staple of hardcore, and transcending the melancholia and fatalism that was a common theme of post-punk, Amebix took on board the musical apparatus of both substyles and turned towards a contemplative, naturalistic direction that subverted the generalisation of how we associate themes with forms. Inspiration comes additionally from the NWOBHM of early Motorhead and Judas Priest in the crunching, percussive guitar playing that made itself a staple of speed metal and subsequently death metal. Drums batter clearly as if to stadium anthems, and boom with an echo one would clearly associate with said decade. Droning riffs make an appearance and have a harmonic depth to them that evoke the archaic and the dystopian much like Burzum and Godflesh simultaneously would do in their most prominent work. Whereas the metal subgenres of the 1980′s slowly influenced one anothers musical language, Amebix single handedly introduced new themes and formats that would become the structural basis of future acts to come, and alongside their compilation album No Sanctuary, this important work deserves it’s applause.

Coming from the anarcho-punk school of musical and ideological tradition, and finally releasing this, their debut full length in 1985, Amebix had already released a series of excellent EP’s in the early half of the decade. The unique character of their music was a sound that fused the violent hardcore punk of Discharge with the circulative, repetitious song structures that were a staple of post-punk acts such as Killing Joke and Public Image Ltd. Escaping the social-activist themes that were a staple of hardcore, and transcending the melancholia and fatalism that was a common theme of post-punk, Amebix took on board the musical apparatus of both substyles and turned towards a contemplative, naturalistic direction that subverted the generalisation of how we associate themes with forms. Inspiration comes additionally from the NWOBHM of early Motorhead and Judas Priest in the crunching, percussive guitar playing that made itself a staple of speed metal and subsequently death metal. Drums batter clearly as if to stadium anthems, and boom with an echo one would clearly associate with said decade. Droning riffs make an appearance and have a harmonic depth to them that evoke the archaic and the dystopian much like Burzum and Godflesh simultaneously would do in their most prominent work. Whereas the metal subgenres of the 1980′s slowly influenced one anothers musical language, Amebix single handedly introduced new themes and formats that would become the structural basis of future acts to come, and alongside their compilation album No Sanctuary, this important work deserves it’s applause.