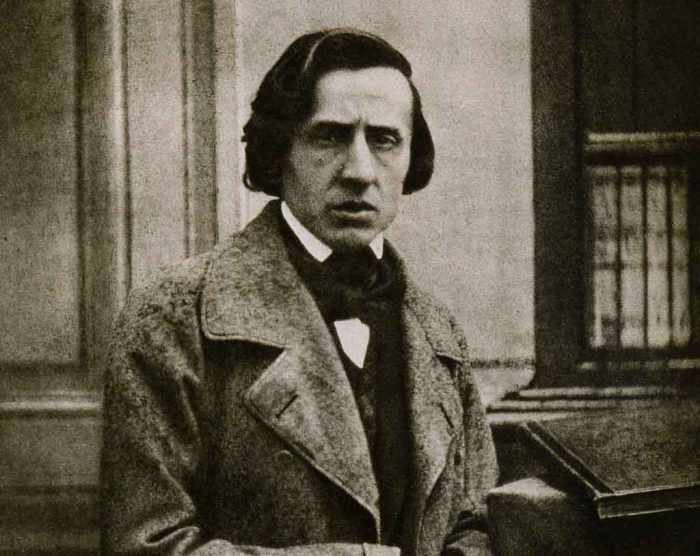

Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849) was a Polish composer and virtuoso pianist who lived out most of his brief but stellar career in Paris, where he died of tuberculosis at the age of 39.

Chopin mixed with the musical elite of his day, developing friendships with top composers and performers, particularly with the Hungarian virtuoso and proto-Hessian, Franz Liszt. He was not keen on public performance, a fact reflected in the intimate atmosphere of his music. However, he was a very successful piano teacher, and managed to earn comfortable wages by giving lessons to the Parisian elite and their children. His health was always bad, and his short life was troubled, but it was also intensely productive, and his body of work remains some of the most emotionally compelling and technically demanding music of the Western classical canon.

Though Chopin’s technical ability and fluency in classicist forms is undeniable, the most enduring element of his work is the profound musical intuition from which its construction seems to arise. Perfectly capable as he is of constructing a fine piece within traditional forms, his best work seems to occur when he listens closely to his own material, and allows it to naturalistically develop and suggest its own structure.

Chopin wrote most of his works for his own instrument, the piano, intending them for performance mostly by himself, usually in front of a few friends. The organic origin of these works shows in their fluid structure and their patient development; the changes that come at exactly the time where they will make the most emotional impact, not necessarily where they would theoretically make the most structural sense or be most immediately pleasing. This characteristic brings him close to underground metal, music in which there is both no divide between composer and performer and, ideally, little concern for audience expectations, but where emphasis is instead placed on genuine, valuable and intense expression.

A great example of Chopin’s emotional intensity, technical ability and structural ingenuity is his second piano sonata, in b flat minor. Although most of the piece’s movements are written broadly within conventional forms, the first being the expected sonata form and the next two being large ternary forms, Chopin manages to create the sensation that this large scale architecture arose naturally from the material, instead of being imposed on it.

We often find in the work of Romantic composers, even in the some of Chopin’s lesser works, a conscious attempt to hide underlying classical forms through over-extended or jarring transitional passages. This sonata has no need for such tricks: the thematic material and the relationships between it are so strong that the flow is seamless throughout. The material itself is of a mostly lyrical and impassioned nature, the axis for most of the themes being melodic. It is thus that the howling arpeggios of the fourth movement come as an intense shock, especially after the famous “Funeral March” of the third movement (which Candlemass covered on Nightfall). Even more rattling is the movement’s swift and violent conclusion. Though seemingly pointless, placing this little movement here is a stroke of narrative genius; it lets the listener know the piece is irrevocably over, and yet it feels unsatisfactory, it leaves one with a melancholy longing. The technique is similar, although the effect is altogether different, to the one used in Burzum Det som en gang var, also a piece organized in four main sections, whose last riff comes rather unexpectedly and then simply fades off into the distance.

There is another very important element that links Chopin’s music to underground metal: his great ability to be impressively creative within self-imposed limitations. The most evident of these restrictions is of course instrumental, as he chose to write most of his music for the solo piano. Obtaining strong results from a limited instrumental palette is of course a very familiar concept to a fan of underground metal. His spectacular waltzes and mazurkas also show him extending a limited rhythmic format to powerful expressive and structural heights, without ever abandoning it entirely. It is in these smaller pieces that Chopin’s tendency to generate structure from content is at its most alive.

A piece with seemingly unexceptional or bland material, such as the Prelude No.4 in E minor, is turned by clever and patient development into a masterpiece, whose economic simplicity only serves to emphasize the power of each event, however minor it may seem. The piece revolves around the thwarting of tonal expectations, a simple enough technique out of which Chopin carves a funereal dirge of both enormous emotional impact and absolute structural perfection. Chopin transforms formal and instrumental restrictions into challenges, forcing himself to find creative avenues around structural problems. This may be one explanation behind why practically all of Chopin’s best pieces are driven by strong melodies; he leaves himself no place to hide.

The Nocturnes are the obvious place to start with the music of Chopin, and for good reason. My personal recommendation would be Claudio Arrau’s 1978 set. Though not all the Preludes are equally good, the whole set is definitely worth a listen, and Martha Argerich’s 1977 DG recording is one of the finest options out there, and it also contains a marvelous rendition of the second Piano Sonata. Also of note are Dinu Lipatti’s disc of Waltzes for EMI and Krystian Zimmerman’s 1988 DG disc of Ballades and miscellanea. Outside the world of solo piano Chopin shines less, even his piano concertos suffer from a poor understanding of the orchestra. This can only serve as further proof that Chopin’s genius lay in his musical intuition, through which he allowed pieces to develop themselves organically in order to reach greater heights of expression, as opposed to merely accommodating themselves to an abstract formal plan. The kinship between Chopin’s fiercely expressive, instrumentally virtuosic and structurally organic style with underground metal is a clear one, and all Hessians are strongly advised to acquaint themselves with the Polish master.

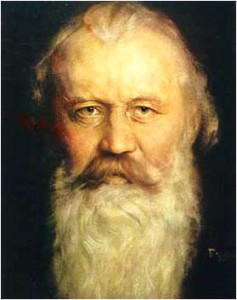

10 Comments Born in Hamburg, Germany in 1833, Brahms exhibited virtuosic abilities as a child. Much of his childhood was spent playing around the local scene including dance clubs (by his own account, “brothels”). As a result, some have concluded that Brahms suffered sexual trauma as a child, but there’s no evidence.

Born in Hamburg, Germany in 1833, Brahms exhibited virtuosic abilities as a child. Much of his childhood was spent playing around the local scene including dance clubs (by his own account, “brothels”). As a result, some have concluded that Brahms suffered sexual trauma as a child, but there’s no evidence. The Death Melodies Series (DMS) continues with Russian Romanticist composer Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky.

The Death Melodies Series (DMS) continues with Russian Romanticist composer Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky.

Quite possibly the most well known composer to ever walk this planet, Ludwig van Beethoven’s music has inspired the world for two centuries. Beethoven ushered in the Romanticist Period after he was under the guidance of Joseph Haydn in which he studied and performed works by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. His Mozartean mastery furthered his reputation as a performer and when Beethoven sought to compose, he started out with heavy influences from his Classical Period contemporaries.

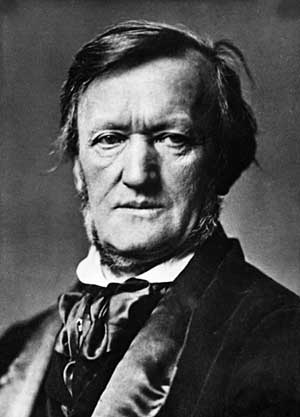

Quite possibly the most well known composer to ever walk this planet, Ludwig van Beethoven’s music has inspired the world for two centuries. Beethoven ushered in the Romanticist Period after he was under the guidance of Joseph Haydn in which he studied and performed works by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. His Mozartean mastery furthered his reputation as a performer and when Beethoven sought to compose, he started out with heavy influences from his Classical Period contemporaries. The Death Melodies Series (DMS) continues with modernist Richard Wagner.

The Death Melodies Series (DMS) continues with modernist Richard Wagner.

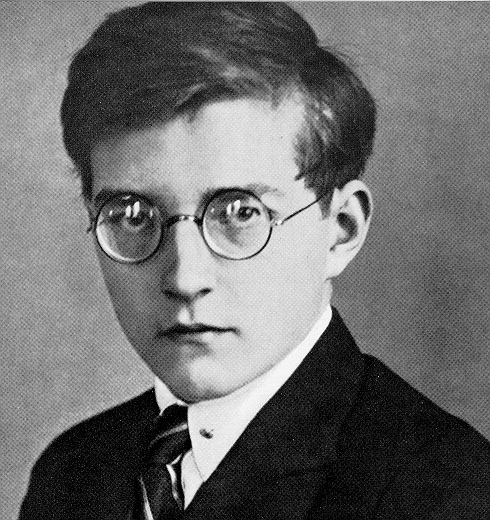

Rachmaninov was born in Russia in 1873 and died in 1943. After the Russian Revolution, he spent most of his time in the US and Europe. He’s known as a late Romanticist while Modern styling was becoming prominent. He’s widely considered a virtuoso on piano, which his piano concertos have become standard in classical music performance.

Rachmaninov was born in Russia in 1873 and died in 1943. After the Russian Revolution, he spent most of his time in the US and Europe. He’s known as a late Romanticist while Modern styling was becoming prominent. He’s widely considered a virtuoso on piano, which his piano concertos have become standard in classical music performance. The Death Melodies Series (DMS) continues with more Baroque.

The Death Melodies Series (DMS) continues with more Baroque. Le Tableau De L’Operation De La Taille (in 17th Century French)

Le Tableau De L’Operation De La Taille (in 17th Century French) The Death Metal Underground (DMU) is proud to present the Death Melodies Series (DMS).

The Death Metal Underground (DMU) is proud to present the Death Melodies Series (DMS).