Article by David Rosales

As another year ends and a new one begins, many “best of” lists pop up here and there, among them our own here at DMU. While others may be eager to know about what is ever new, we are more interested in what stands the test of time. Today we will look at some albums that were highlighted here as the foremost products of the year 2013, which was a year of renewal, great comebacks, startling discoveries and a general wellspring of inspiration. In the opinion of this writer, 2013 has been the best year for metal in the 21st century.

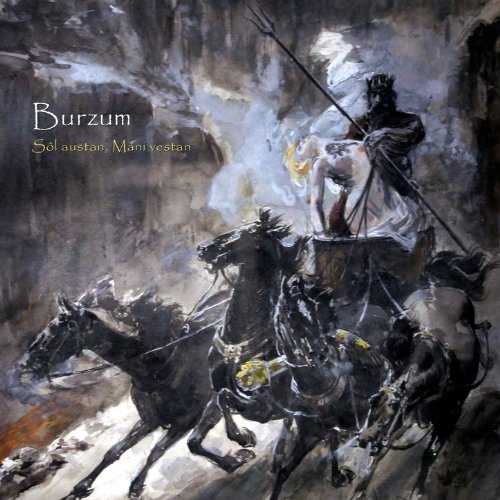

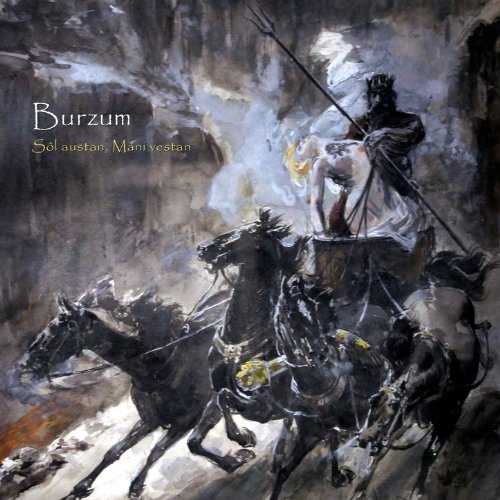

To start off, we shall pay respects to long-lasting acts with a black metal background, namely Graveland, Summoning and Burzum. While the last has left the metal camp for good, its approach and spirit is still very much enriched by the essence of the deepest metal infused with transcendental values. Summoning is still doing their thing, ever evolving, trying a different permutation of their unique style. Fudali’s project has become the warrior at the frontlines of the strongest nationalism grounded in music that uplifts the heart with an authentic battle feeling (as opposed to those other bands playing funny-jumpy rock and acting all “dangerous”).

Sôl austan, Mâni vestan is an ambient affair that uses short loops which revolve around clear themes in each track. The approach is a little formulaic, thereby limiting the experience with a feeling of repetition. However, as with many good works of art, this self-imposed canalization serves to speed the result in a direction. As with a lot of Burzum’s work, this is a concept album that must be listened to as a whole. When this is followed and one stops looking for novelty and instead concentrates on the details that bring variation within the familiar landscape, the somewhat arduous experience brings great rewards once the summit is reached and the journey is taken more than once.

Something similar can be said of the slightly pop-minded Old Mornings Dawn. This effort by Summoning certainly lacks the density of their masterpiece, Dol Guldur, but is no less effective, although perhaps shallow. But what isn’t shallow when compared to that masterpiece? As with every Summoning album, Old Mornings Dawn has a very separate personality, and in this case, it is one of heroism, light, regeneration and hope. Something that will never leave the band’s trademark sound is the deep feeling of melancholy and longing for ruins.

Graveland materializes in Thunderbolts of the Gods one of their most warlike efforts to date in a smooth trajectory that has gone from rough-pagan to long-winded and epic to heroic war music. What raises this offering above others in Fudali’s current trend is the awesome bringing forth of destructive energies mustered in the imposing drumwork. Gone are the clumsy rhythms of Cold Winter Blades and the redneckish tone of the (nonetheless great) album Following the Voice of Blood. This is the technically polished and spirit-infused summit of this face of Graveland.

One of the most deserving releases of 2013 was Black Sabbath’s 13. More expectations could not have been placed on anyone else. Yet the godfathers of metal delivered like the monarchs they are: with original style, enviable grace, magnificent strength and latent power. Along with the last three albums just mentioned, this album shows itself timeless in the present metal landscape. It encompasses all that it is metal, and brings it back to its origin. This is an absolute grower which will age like the finest wine and is, in my opinion, the album of the year of 2013.

In 2013, Profanatica finally achieved amazing distinction with Thy Kingdom Cum, which can be considered the fully developed potential of what Ledney presented in the thoroughly enjoyable Dethrone the Son of God under the Havohej moniker. To say this is the natural outcome of Profanatica’s past work is as true as it is misleading in its implications. This is not just a continuation of what the band was doing before, but a deliberate step, a clear decision in the clear change in texture quality that means the world in such minimalist music where a simple shift in technique or modal approach defines most of the character of the music.

Cóndor’s Nadia was probably the hidden pearl of the year. Never mind the metaphor of the “diamond in the rough”, there is nothing rough about this. It is polished, but it is hidden. The shy face of this beautiful lady is covered by a veil that turns away the unworthy, the profane! This is immortal metal artwork which to uninitiated eyes and ears seems but like the simple, perhaps even amateur, collection of Sabbathian cliches and tremolo excuses of an unexperienced band. The knowledgeable and contemplating metal thinker recognizes the Platonic forms under the disfigured shapes.

Imprecation’s Satanae Tenebris Infinita and Blood Dawn by Warmaster draw our attention to the strong presence of a more humble but profoundly (though not obviously) memorable album and EP. These will stand the chance of time, but will not necessarily remain strong in the mind of a listener in a way that he feels compelled to come back to them often.

Dark Gods, Seven Billion Slaves by VON seemed more enticing at the time. It’s definitely a solid release, but it is however a very thinly populated album with more airtime than content. Whatever content it has is also not particularly engaging. The enjoyability of this one is a much more subjective affair and like a soundtrack is more dependent on extra-musical input from the listener’s imagination.

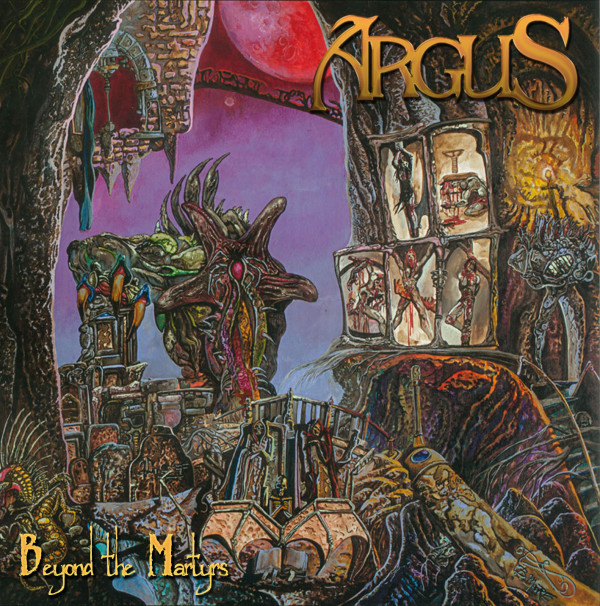

As delightful as the three heavy metal albums Argus Beyond The Martyrs, Blitzkrieg Back From Hell and Satan are, the intrinsic qualities of their selected subgenres makes them a difficult candidate for long-lasting and profound impact. That is not to say they have no lasting value. If anything, these are albums one can come back a thousand times and perhaps they will not grow that much, but they will never truly grow old.

Autopsy’s Headless Ritual is one of the strongest yet most understated albums of the year. The extremely rough character of the music may contribute to how it carelessly it can be left behind. Fans of brutal music will find it little different from the rest and will quickly forget it. Fans of wider expressions and deeper thoughts will pass it by with little interest. Such is the tragedy of this very respectable album.

A few stragglers in this group; Master’s The Witchhunt, Centurian’s Contra Rationem, Derogatory’s Above All Else, and Rudra’s RTA proved to be more impact and potential than manifest presence. These will remain fun and quaint for a very occasional listen, perhaps even a sort of throwback feeling, but lacking the long-lasting impact of others in this list.

A special mention is deserved by Into the Pantheon, the essential synthesis of Empyrium, being their most revealing, powerful and clear release. While not outwardly metal, this live recording everything that is to be metal at the level of character and spirit. As such it is the perfect closing note for this recapitulation and reevaluation of past selections.

27 CommentsTags: argus, autopsy, best of, Black Metal, black sabbath, burzum, condor, death metal, empyrium, graveland, imprecation, master, profanatica, re-review, subjective, Summoning, underground metal, von