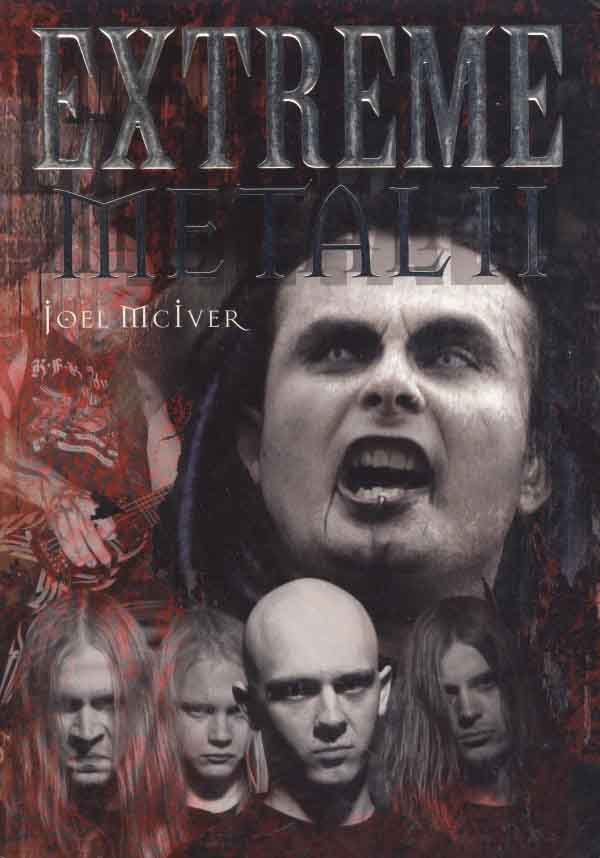

For a short book that you can finish in an afternoon, Extreme Metal by Joel McIver packs a great density of information of unusual breadth into this deceptively simple volume. Comprised of brief introductions and then combination profile, history and review of the major works of each band, this book applies a flexible strategy to information and dishes out more on the more important bands but refuses to leave out essential minor ones.

McIver released two versions of this book: an original (2000) and this update (2005). With each edition, the book gains more factual information and the writing kicks it up a notch. I first read Extreme Metal I shortly after it came out in a bookstore and noted how some of the writing was boxy and distant, but how (thankfully) it did not drop into the hipster habit of insider lingo and extensive pointless imagery. In Extreme Metal II, McIver writes according to the journalistic standards of the broader media and skips over the conventions of music journalism and especially metal journalism which are less stringent. If there is an Extreme Metal III, the language will be even more streamlined and relaxed.

A good book on metal includes not only information but interpretations; all books filter by what their authors think is important, and one of the strengths of Extreme Metal is its ability to zoom in on not just the larger bands but a number of smaller ones that contributed to the growth of the genre. With each of these bands, McIver presents the information as relevant to a metal fan interested in learning the genre but also in hearing the best of its music. After an introduction by Mille Petrozza of Kreator, Extreme Metal launches into a brief history and afterward is essentially band profiles in alphabetical order. McIver includes all of the big names that one must include especially in any book that wishes to have commercial success, but devotes a fair amount of time to focus on the underground and the odd details that complete its story. He displays a canny instinct for rooting out the important, even if obscure, and relating it to the progress of the genre as a whole.

Written in a conversational but professional style, the book unloads a large amount of information with a low amount of stress and reads much like an extended magazine article covering the growth of the extreme metal genres. Depending on what sub-genres a listener enjoys, parts of the book will be skimmed, much as some Hessians glaze over whenever anything related to nu-metal emerges. McIver displays the instincts of a metal listener and refuses to sugar-coat his opinions, but does not drift into the trendy internet sweetness-and-acid diatribes that afflict those who rage at the excesses of the underground. Instead, the book assumes that its readers are open-minded enough to listen to any good heavy metal and tries to dig out the best of it, even if those standards need to expand when nu-metal or metalcore float by.

Massacra

Massacra was a French ‘neo-classical death metal’ band and was formed in 1986. Three demos landed them a deal with Shark Records from Germany and later, the major label Phonogram. However, the band was put on hold in 1997 when a founding member, Fred Duval, died of skin cancer at only 29. Some members of the band formed an industrial band, Zero Tolerance, and released an album on the Active label.

Recommended Album: Final Holocaust (Shark, 1990)

Among the truckloads of paper published since Lords of Chaos convinced the industry that money could be made in books about underground metal, Extreme Metal distinguishes itself by being open-minded and yet straight to the point. Most books pass over perceived minor bands like Massacra, Autumn Leaves and Onslaught, but this book fits them into context and explains their relevance in a way that is both enjoyable and informative. While major bands like Metallica will always get more coverage, here McIver works to tie his write-ups of those bands in with traits of other bands who both helped make that success happen and carried it forward.

McIver has gone on to write other books including a best-seller about Metallica, a biography of Max Cavalera of Sepultura, retrospectives of Motorhead and Black Sabbath, a band history of Cannibal Corpse and most recently, a book about alternative band Rage Against the Machine. He demonstrates comfort at every level of above-ground and underground bands, but his instinct as a fan makes him a writer worth reading as he tears through metal, sorting the entropy from the growth. While one can write about underground metal to any depth, Extreme Metal strikes the right balance of information and expediency and produces an excellent first step for any fan or researcher looking into these sub-genres of heavy metal.

1 CommentTags: books, extreme metal, joel mciver, metal books, omnibus press