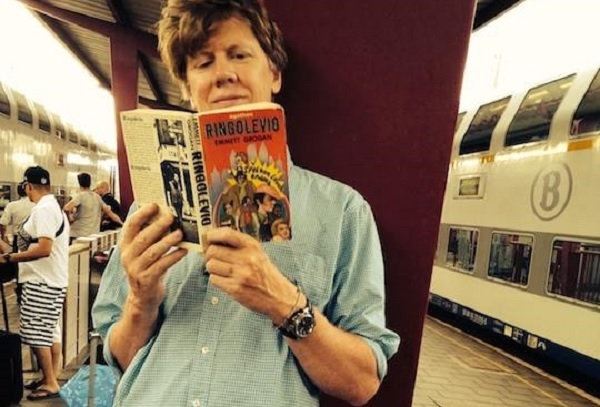

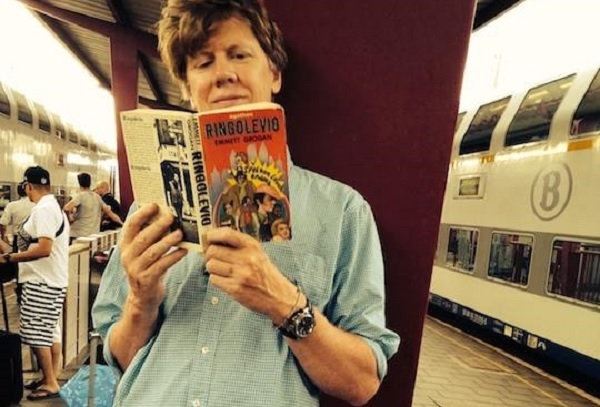

Most people believe that “trolling” happens on the internet and that trolls are a group like organized crime. Instead trolling is a method and trolls are any who troll, such as when Sonic Youth guitarist Thurston Moore trolled black metal fans recently.

Having been around media and rock fans alike — two groups heavily invested in the pretense of self-styled self-image — Moore spotted a good mark for a brutal troll when he saw one. Thus with an offhanded comment, he lit the rage-fires of ten thousand fedora-blessed basements.

Black Metal is music made by pussies of the lowest order, and we felt it was necessary to investigate this aberrant anti-music behavior. We feel like the sound and attitude of black metal is a loss of self, life, light and desire in a way where it becomes so negative that a whole new bliss arrives where we become super pussy.

The guitarist elaborated later:

Black metal, it doesn’t even consider itself music. In fact, it doesn’t want to be confused with any kind of music because it’s something else entirely. It’s a voided concept from its start [laughs]. It’s all about complete disintegration of existence. It’s a music that uses the elements of rock instrumentation but it’s so anti-everything that, for me, it doesn’t matter what you say about it because it doesn’t exist. I figured I would just write something ridiculous about it. And boy, did black-metal devotees get really upset by it. You’re not supposed to be alive, so why are you getting upset?

We know that his first statement is a troll because it was the only statement included in the press release, and more importantly, it makes us of a dual meaning in the term “pussy” to wind up the angry denizens of vans down by the river. Moore has been around the alternative rock scene too long to be anything but scrupulously politically correct, so it is dubious he would ever use the term “pussy” in a sexist manner, but that does not prohibit him from playing off the common usage of the term in the metal community to mean (roughly) wimp or weenie.

It seems to me that Moore is having a bit of fun with the term and is distilling it back to its more Victorian usage where it refers to housecats as distinctive from street cats. Meaning that black metal fans are sleek, well-fed, pampered and most likely neutered. Domesticated. Not a threat to anything, probably not even mice, despite the face paint.

Black metal deserves this attack in 2014. From 1989-1994, the genre thrived amidst murder, politically incorrect statements and church arsons, but also some really excellent music. Since that time, much like modern Western civilization, black metal has been cruising on the wealth of the past. With a few exceptions like Demoncy, Beherit and Sammath black metal has fallen so far short of its historical peak that it resembles a collapsed civilization. Among the ruins of an ancient past of greatness, the remnants of a broken social experiment play and achieve nothing of any importance, but when challenged in a pub, they are quick to remind us all that they were Romans, once.

The usual crowd of poseur wannabes at the FMP and NWN forums have been cruising on the reputation of black metal for two decades now. They act like the worst street toughs ever and remind us that not only were they Romans, but once they burned churches and murdered people. However, they are most likely to come home from their jobs as Facebook consultants and hang around their loft apartments drinking craft beer and arguing over the minutiae of which indistinguishably bland “black metal” band has more “atmosphere” than the others, when in fact all post-1994 black metal sounds the same because none of it is written about anything. It is all variants on an aesthetic, and nothing more. The guts of it are gone; it has abolished itself.

Black metal was born as a reaction — both to and against death metal, which was experiencing a rare period of commercial success in the early ’90s — and thus, it had a rigid definition before it even had a body….Euronymous’s Helvete was to Norwegian black metal what MacDougal Street was to the ’60s Greenwich Village folk scene, and his views were considered gospel. Death metal was “trendy” and “fun,” said Euronymous; well, black metal rejected trends and fun…For Euronymous, the primary essential element for music to be defined as “black metal” was Satanism. “If a band cultivates and worships Satan, it’s black metal,” he said. “What’s important is that it’s Satanic; that’s what makes it black metal.”

Moore keyed into this pointlessness. When a genre can easily merge with indie rock and heroin and form a “supergroup” like Twilight, and when droning nobodies like Deafheaven and Wolves in the Throne Room are accepted as normal parts of the genre, it is dead and buried. It has lost its sense of “genre,” or having artistic purpose, and now is just another shade of wallpaper in which we can drape the usual thoughtless rock music so that it can be sold to a new generation of domesticated rebels.

Black metal had relevance when it was a movement of artists who felt Western civilization had gone down a bad path and had a suggestion of how to reform it: remove its morality of protecting the individual, which translated into protecting the vast herd of anonymous people who fear that someone might wake up and discover that all of society built on morality is a shame. It rejected all that was “good,” and embraced all that was functional yet “bad,” building on 300 years of Romanticism which encouraged the same. As an artistic movement, it had purpose, which meant that not everyone could participate. As soon as they could, the Hot Topic generation seized hold of this music and turned it into a neutered, tame and compliant version of itself so that it would not offend their personal pretense or make them actually controversial, although they gladly accepted the appearance of the same.

As guitarist for Sonic Youth, Moore knows this well. He made his career by dressing up the dissonant protest rock of the 1960s in the veil of distortion inspired by the Ramones, and essentially carries on every trait of the most-played out decade of music ever in a new form. Like a salesman, he finds a way to make you buy the same ugly vacuum cleaner in a new color because now it has a gizmo that winds up the cord faster. But he also knows music, and he is right to bash black metal. It is a pussycat, fat and perched on a luxuriant sofa, which hisses and holds out a trembling claw as we approach, reminding us that it was a tiger, once.

h/t I.O. Kirkwood / Metal Descent

70 CommentsTags: Black Metal, poseurs, thurston moore, trolls