DeathMetal.org continues its exploration of radio with a podcast of death metal, dark ambient and fragments of literature. This format allows all of us to see the music we enjoy in the context of the ideas which inspired it.

DeathMetal.org continues its exploration of radio with a podcast of death metal, dark ambient and fragments of literature. This format allows all of us to see the music we enjoy in the context of the ideas which inspired it.

Clandestine DJ Rob Jones brings you the esoteric undercurrents of doom metal, death metal and black metal in a show that also exports its philosophical examinations of life, existence and nothingness.

This niche radio show exists to glorify the best of metal, with an emphasis on newer material but not a limitation of it, which means that you will often hear new possibilities in the past as well as the present.

If you miss the days when death metal was a Wild West that kept itself weird, paranoid and uncivilized, you will appreciate this detour outside of acceptable society into the thoughts most people fear in the small hours of the night.

The playlist for this week’s show is:

- Slayer – Necrophiliac

- Cruciamentum – Rites to the Abduction of Essence

- Extracts from Hugh Selwyn Mauberley by Ezra Pound (read by the poet)

- Blaspherian – Invoking Abomination

- Stravinsky – Symphony of Psalms, first movement

Without a doubt the Internet has been the great communications revolution of our time, changing the shape and the pace of commerce and culture alike.

For metal, the internet has primarily meant a far wider audience-reach, enabling the growth of the larger labels and festivals into massive unit-shifters, and allowing even the feeblest of bedroom bands to find five minutes of someone’s attention.

High speed downloading has made metal music across the board more heavily pirated than ever, yet simultaneously given the whole genre far more exposure than before.

Perhaps most significantly, the ability it gives individuals to both broadcast and share content has allowed forgotten bands – who, for the quality of their work, should have been classics – to reach audiences and acclaim they previously missed out on.

The internet, like society itself, however is not one great monolithic thing, but simply a series of networks, meeting points and exchanges, always changing and adapting piecemeal to developments in both technology and culture, and in-turn shaping the society it forms part of.

Where in the early years of the internet small localized networks allowed for basic communication and facilitated real world interaction, the present-day internet has through its size, speed and centralization become like an immersive parallel world, spawning its own cultural and even linguistic tropes; substituting in many ways for tangible real world interaction.

Three years ago Wired magazine actually pronounced the death of the world wide web, noting that after hitting a peak around the year 2000 the number of sites we visit and ways that we access them has become narrower and narrower. Sites like Facebook, Google and Wikipedia have an increasingly dominant share of global traffic, in the process marginalizing independent sites and narrowing both the kinds of information we receive and how we consume it. This is not necessarily a straight battle between the evil-empire corporations and the idyllic small world everyman (in the way that some activists like to portray politics in general), but a trade off between different advantages and disadvantages.

Fewer sites means greater efficiency and organisation with which content can be managed and shared, and also ups the standard for site design, development and security. The downside is that it enforces a steady uniformity on both the way in which things are communicated and on the prominence they are able to take. No one thing any longer can particular amount to more than the same little square box of information that makes up any search engine result or item on a social network feed, and everything comes and goes as quickly as anything else does in the same continuous stream.

Also, perhaps counter-intuitively, it puts an increasing amount of power in the hands of ‘the community’ in the most amorphous and anonymous sense. Facebook for example, beyond a few specific algorithms, is far too big for those that run it to police the content everyone posts on it, so it relies on its users to flag antisocial content and determine what should be shut down. Obviously such a system is hypothetically open to exploitation from particular groups, but above all it enforces a status quo line of thinking on what is to be considered legitimate or acceptable information.

So the internet as it currently exists has helped put limits on both what we say and how we say it.

Metal music before the growth of the internet had been a largely underground cultural phenomena: specifically spurning group-think methods of quality-control and organizing more along Darwinian/Nietzschean lines, wherein the strength and boldness of the music determined its ascension to and effectively perpetual status.

The growth of the internet has therefore sometimes jarringly co-existed with metal. Early hessian websites like the Dark Legions Archive and the BNR Metal Pages set the tone for metal on the internet as it had existed in the real world up until then: an enthusiast-centered mixture of devotion, and unsparing praise for bands and albums whose quality made them deserving. Newer and essentially more democratic net developments however harbor a conflict between those who represent the old ways, and those used to the confused standards, egalitarian platitudes and big media saturation that characterize metal in its later years.

- Birth A.D. – Shortbus Society

- Primordial – The Black Hundred

The democratization facilitated by the internet hasn’t so far created a widespread resurgence in quality. The re-exposure of forgotten musical gems and past scenes has not so much led to a revival of the spirit that went with those bands, as much as it has contributed to the stagnating plurality of lifestyle options and consumerist flavors offered by our crumbling utopia. For example, the growth of retro-thrash, complete with authentic caps, sneakers, d-beats, nuclear-themed artwork and Anthrax-style vocals – or the retro Swedish style bands, all playing roughly the same bouncy down-tuned death metal through a boss hm2. Outwardly they ape the sound of the genuine article, but beneath the surface offer little of substance, never really aspiring to do more than just reproduce the appearance of those older experiences. Fundamentally this is no different than the obvious and easily called-out hipster cult – that fetishizes the random ephemera of past fads for the sole aim of shallow self-aggrandizement. The retro-thrashers and their like are metal’s own version of hipsters – products of the dead end civilization, endlessly and emptily regurgitating its own past for lack of any meaningful inner direction.

In this respect, the internet has only heightened the dopamine-addicted individualism of the consumer society and absorbed metal into that; allowing more of us to wall ourselves off inside our own heads – where we can play out whatever inconsequential fantasy we feel like and make affectations of action and authenticity without actually living it.

For those who know how to use it – and are cautious enough to keep its negative effects at arm’s length – the internet can be an invaluable resource for both sharing ideas and educating oneself. Metal on the internet need not be any different. Enough great music, previously under the radar, can (and has) come to light because of the internet to justify its utility. And, provided you are smart about it, it can also be an effective promotional tool for quality metal and for higher standards; as long as, above all else, you are careful not to get sucked into treating it as the ego feedback loop that most people use it for.

DOWNLOAD

3 CommentsTags: podcast

The International Journal for Community Music has issued a call for papers seeking research on “the heavy-metal community (and its communities) and the spaces and practices that shape heavy metal music as community music.”

The International Journal for Community Music has issued a call for papers seeking research on “the heavy-metal community (and its communities) and the spaces and practices that shape heavy metal music as community music.” DeathMetal.org continues its exploration of radio with a podcast of death metal, dark ambient and fragments of literature. This format allows all of us to see the music we enjoy in the context of the ideas which inspired it.

DeathMetal.org continues its exploration of radio with a podcast of death metal, dark ambient and fragments of literature. This format allows all of us to see the music we enjoy in the context of the ideas which inspired it.

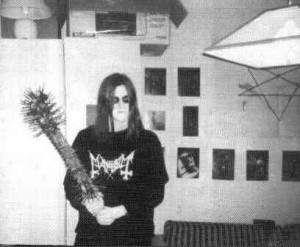

Burzum composer Varg Vikernes has posted a “goodbye” to his old self as a metal composer and in a sentimental posting, announced his retirement from metal and his intent to pursue ambient music alone.

Burzum composer Varg Vikernes has posted a “goodbye” to his old self as a metal composer and in a sentimental posting, announced his retirement from metal and his intent to pursue ambient music alone. The semi-reclusive Varg Vikernes, sole composer of

The semi-reclusive Varg Vikernes, sole composer of

Why is metal riff-crazy? These twisted little quasi-melodies of sliding power chords, notes and harmonics are tiny puzzles for our brains. Now science hints at why metal loves them.

Why is metal riff-crazy? These twisted little quasi-melodies of sliding power chords, notes and harmonics are tiny puzzles for our brains. Now science hints at why metal loves them.