In the night, one can hear many noises. Some sound scary, and others signal scary events. For example, the roar of an animal is disturbing, but to someone alone in a house a stealthy footfall or the click of a lock is scarier. Similarly in art, the context of a sound defines its significance, and what makes music frightening is the meaning it encodes.

Among all forms of art, what makes heavy metal unique is that it embraces disturbing sounds which are not ugly but which portend disturbing patterns found in reality. Heavy metal is the music of the apocalypse, and whether warning it off or cheering it on or both, achieves this heaviness through the context it conveys.

What makes heavy metal heavy?

Both fantastic and literal, heavy metal explores the ideas our society will not endorse. It is not protest music, whining “it should not be” into a secondhand microphone, but a war-like genre which describes destruction with the joy of a painter who could use it as a color in a new epic landscape. Metal is about the experience of life, but it disciplines that with a clear sense of reality and consequence, as is appropriate for “heavy” conversation. Where society hides from fear and allies itself with the threat of the consequences of fears, metal allies itself with death to dispense fear.

Both fantastic and literal, heavy metal explores the ideas our society will not endorse. It is not protest music, whining “it should not be” into a secondhand microphone, but a war-like genre which describes destruction with the joy of a painter who could use it as a color in a new epic landscape. Metal is about the experience of life, but it disciplines that with a clear sense of reality and consequence, as is appropriate for “heavy” conversation. Where society hides from fear and allies itself with the threat of the consequences of fears, metal allies itself with death to dispense fear.

When metal first arrived, new fans began to understand what made Black Sabbath “heavy”: the patterns which revealed the thinking behind such noises, putting context to the fear they instilled. Thundering distorted riffs were not new; Blue Cheer had done that. Neither was aggression; Iggy Pop had done that. But Black Sabbath, inspired by horror movie soundtracks, came up with a new style of music that used melodic phrases played in power chords, and by targetting the weighty topics that social conversation did not admit, creating a terrifying form of art.

Rock music had grown through the 1960s from simple boyfriend-girlfriend pop to apocalyptic rock like the Doors or King Crimson in the same way the Beatles rejected their sugarpop roots to become morbid and political. Whenever given a chance, the music reverted to a simple, tolerant, peaceful hedonism that hid its escapism and narcissism. The future members of Black Sabbath, upon seeing a horror movie and wondering if people would ever pay to have that experience in rock music, created the antithesis to distracting escapism: a descent into the complex and violent world of reality.

Its heaviness migrated into a different style of composition: other bands wrote songs around open chords which were strummed in a repeated pattern, and then modulated, while Black Sabbath used moveable power chords to make phrases into riffs and it was the change in those phrases that communicated a difference in outlook. It was more like classical music, where harmony is so well-studied that it is used as a device toward “narrative,” through-composed pieces where the change in motifs and their accompaniment conveys a string of moods that like a mythology or a fable convey the idea of a journey from one point to another.

With this development, they gave meaning to the sound. Its context of topics gave its heaviness form, but musically it was heavy as well, using thundering chords that stripped out traditional harmony and made the riff instead, like the nihilistic voice of an angry god, speak the truth that completed the poetry of contrast in each song. By throwing away form, and the form of socialization which “peace” and “love” implied, Black Sabbath brought danger back into a stagnant modern life — specifically, the danger that in all the attempts to stay away from the darkness, we as a civilization had missed an essential truth.

What does metal believe?

As an art form, metal has continuously developed visions of a human apocalypse lingering in the absence of our willingness to face reality. Reality is, as the saying goes, not entirely pleasant, and so is less popular than simple partial truths called “symbols,” which create an illusion of completeness by super-simplifying reality. Morality is not scientifically accurate but it is more comforting to our minds to have two options instead of nearly infinite ones.

During its maturation, metal wavered in and out of the public illusion, called “consensual reality,” which is the alternate reality of values most people use to navigate their lives. Consensual reality includes the symbols people want to believe in and, reinforced by preference-enabling activities like democracy and consumerism, makes itself “real” by the fact that most people believe it to be true. This public illusion takes many forms and metal has not been immune, but is strongest when it kicks aside the illusion and goes for the kind of heavy contexts that always made good ambiguous truth.

During its maturation, metal wavered in and out of the public illusion, called “consensual reality,” which is the alternate reality of values most people use to navigate their lives. Consensual reality includes the symbols people want to believe in and, reinforced by preference-enabling activities like democracy and consumerism, makes itself “real” by the fact that most people believe it to be true. This public illusion takes many forms and metal has not been immune, but is strongest when it kicks aside the illusion and goes for the kind of heavy contexts that always made good ambiguous truth.

One view of metal is as a reality mediator showing the darkness underlying our pleasant illusions, and that in doing so, it is not deconstructive but attempts to make clarity of life by finding beauty in the dark and heavy as well as the light. As a holistic approach, this outlook negates both dualistic worlds (heaven, hell) and secular morality in favor of a scientific, historical and abstract design-oriented perspective on life. This then returns us to the idea of metal as orthodoxy, or a genre in which there is a clear direction and those who deviate from it are parasitizing on the popularity of the genre while weakening it with ideas that oppose it.

The terms “sell out” and “poseur” arose in the 1970s to refer to those of this intention, most specifically the bands like Def Leppard who turned their heavy metal roots into radio trash that was essentially rock music with power chords. A poseur was someone dishonest who adopted the most rigorous pose, or identity-affirming lifestyle and opinions, of a genre but was like all hipsters using it for his or her own benefit and believed none of it. These terms persist to this day.

Any ideology is necessarily orthodox, in that if it does not assert a right way and wrong way of doing things, it is not an ideology at all but an ethic of convenience much like the opinionless, directionless motions of rock music or its deferential humanistic political counterpart. Rock stands for a big party and everyone having it their way; this is a meta-orthodoxy that opposes all orthodoxy.

Metal on the other hand is orthodox and opposes meta-orthodoxy because an orthodoxy of no orthodoxy is a lack of direction. Directionless self-assertion does not address the apocalyptic or religious aspects necessary to unite human thinking toward survival in an apocalyptic time. To clarify reality, metal music embraces nihilism and worships power and beauty, because these things connect us to a reality that will forever seem flawed to us because it is full of horror, doubt, fear and death. However, the metal outlook shows us the wisdom of these things and makes living with them seem “fun,” where rock music and other anti-orthodoxies retreat into human activities and social realities, pushing reality itself far away.

As a result, metal is sandwiched between protest music of the anarchic left and the wisdom of the conservative ancients, forming itself through fantasy into a vision of a more realistic and more enjoyable vision of life. Rock music is a product of the wealth and convenience of a modern time that allows us to have inconsequential lifestyles and opinions, while metal is a revolution against that outlook, a seemingly deconstructive art form that in actuality opposes deconstruction.

We can trace these ideas through consistent beliefs found across metal generations:

- Beauty in darkness. It is not ugly, pounding music but music which discovers beauty in distortion, in anger and terror, in violence and foreboding dark restless relativistic power chords. The point is not to deconstruct, but to go through deconstruction and find meaning. This is evident in the works of Black Sabbath and every metal band since, and is what distinguishes “real” metal from hard rock.

- Worship of power. Unlike pacifying rock music and jazz and “new music” classical, metal music adores powerful, vast and broad simple strokes; it loves the majesty of nature and its crushing final word. It does not have love songs. Instead, its love is directed to forces of nature, including physical forces like storms and intense human experience like war or loss, as if trying to find meaning in these.

- Worship of nature. Linked to metal’s adoration of power is its appreciation for the function, including its “red in tooth and claw” aspects, of the natural world. Where most are repulsed by the idea that combat exists between animals in which one is victor, and one is prey, metal idolizes it. It finds beauty in ruins, in destruction, and in death, as if praising the cycle of life they engender again.

- Independent thinking. Metal does not buy into the individualism of a modern time where the only goal is material pleasure of the self (materialism) and keeping others away by granting them the same (humanism). It prefers the independent thinking that looks for higher values in life, mountains to climb and challenges to be met. Where punk music enmeshed itself in a callow “I wanna do what I wanna do,” metal saw this as part of the same gesture of rock music and discarded it.

These are expressed artistically by the following:

- Dark, morbid themes that clashed with the “love will save us” hippie mentality. These are explained by Black Sabbath as being derived from the horror movies of the day, a genre which features a union between technology and the occult (zombies, werewolves) producing a force humans cannot oppose. Normal technologies and methods cannot defeat it. They struggle against this force but their emotional instability causes them to sabotage one another, and often the dark force wins. Examples from this genre: Mothra, Dawn of the Dead, Alien, The Exorcist, The Shining, War of the Worlds.

- Songs written from short cyclic phrases called riffs, which unlike rock riffs used moveable chords of inspecific harmonic bonding, making the melody and rhythm of the phrase more important than key or voicing. Metal bands tend to use more riffs per song, and not in the traditional cycle of verse-chorus, in a way quite similar to progressive bands like King Crimson and Yes, both of whom used aggressive distortion.

- A focus on the holism of the human effort as determined by our moral state as individuals in a way that can only be described as “religious.” Metal, in addition to sounding eerily like angry Bach-scripted church music, has a similar focus to dogmatic transcendentalism Christianity: what is our future as human beings, and how does how we shape our personalities effect it?

- Bass-enhanced overdriven guitar sound, or distortion, which encloses the primary instrument used in making heavy metal. In rock, guitars and drums come together to emphasize a vocal melodic line; in metal, guitars lead a melodic line for which vocals are a complement and drums a timekeeper, enclosing it in a regularity to give listeners context. The guitar is the loudest single instrument heard and the one that invokes changes in song.

These beliefs and musical techniques reinforce each other. Using distortion and loud music, yet finding beauty in it. Using longer narrative phrases so as to tell a story, creating a holistic view in which emotion emerges, instead of citing pre-configured emotions like rock music does. A darkness and melancholy exhibited in lyrics and imagery, corresponding to aggressive music, expressing a desire to seize all of reality, good and bad together, and make something better of it.

Heavy Metal as Romanticism

We have seen ideas similar to these before in the form of a genre that, once birthed, refused to die, even as history moved on. In fact, it has re-emerged throughout the modern time because it was the step before this new type of rationalism,

Although metal borrows from both classical and Romantic periods of classical music, its most intense similarity is to the Romantic period in literature, which in its later years diverged into Gothic horror and transcendental idealism. Much as embryological theory tells us that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny, or that a fetus goes through the same stages of evolution as its species did to arrive at its current state, metal theory shows us that metal — as a revolt against what rock music stood for, e.g. distraction — forms an embryo which rediscovers its musical past. In this sense, metal is starting with classical and venturing through late Romanticism toward modernism.

Although metal borrows from both classical and Romantic periods of classical music, its most intense similarity is to the Romantic period in literature, which in its later years diverged into Gothic horror and transcendental idealism. Much as embryological theory tells us that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny, or that a fetus goes through the same stages of evolution as its species did to arrive at its current state, metal theory shows us that metal — as a revolt against what rock music stood for, e.g. distraction — forms an embryo which rediscovers its musical past. In this sense, metal is starting with classical and venturing through late Romanticism toward modernism.

According to the experts, Romanticism in literature and music has several tenets:

Romanticism was a response to neo-classicism, which was the most recent form of the surge in rationalism brought about by The Age of Enlightenment. Where the Enlightenment rationale brought individual rights, focus on personal emotion, and a linear logical process by which one could dissect the world and find an absolute response to it, Romanticism both inherited that tradition and began dissolving it. It is for this reason that we can find Romanticist themes abundant, in everything from Star Wars to presidential speeches: the conflict of rationalism-versus-Romanticism has never been resolved.

Unlike modern individualism, Romanticist individualism meant using yourself as the justification for your own wants, instead of trying to find some external justification. As Nietzsche phrased it, “I prefer” and “I find beauty in” are more important than all the equations, statistical summaries, studies cited and popular votes in the world; Romanticism (of which Nietzsche was an ambiguous defender but spiritual comrade) rejects the idea of externalized truths and knowing, and instead prefers a sense of unity between the individual’s aesthetics and a “mythic imagination” which lets them see possibilities in the world using holistic logic, instead of the linear (single-factor) logic used by rationalists.13

The world is too much with us; late and soon,

Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers;

Little we see in Nature that is ours;

We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!

This Sea that bares her bosom to the moon,

The winds that will be howling at all hours,

And are up-gathered now like sleeping flowers,

For this, for everything, we are out of tune;

It moves us not.–Great God! I’d rather be

A Pagan suckled in a creed outworn;

So might I, standing on this pleasant lea,

Have glimpses that would make me less forlorn;

Have sight of Proteus rising from the sea;

Or hear old Triton blow his wreathed horn.

– The World is Too Much With Us, William Wordsworth (1789)

Once upon a time, in some out of the way corner of that universe which is dispersed into numberless twinkling solar systems, there was a star upon which clever beasts invented knowing. That was the most arrogant and mendacious minute of “world history,” but nevertheless, it was only a minute. After nature had drawn a few breaths, the star cooled and congealed, and the clever beasts had to die. One might invent such a fable, and yet he still would not have adequately illustrated how miserable, how shadowy and transient, how aimless and arbitrary the human intellect looks within nature. There were eternities during which it did not exist.

And when it is all over with the human intellect, nothing will have happened. For this intellect has no additional mission which would lead it beyond human life. Rather, it is human, and only its possessor and begetter takes it so solemnly-as though the world’s axis turned within it. But if we could communicate with the gnat, we would learn that he likewise flies through the air with the same solemnity, that he feels the flying center of the universe within himself. There is nothing so reprehensible and unimportant in nature that it would not immediately swell up like a balloon at the slightest puff of this power of knowing.

– On Truth and Lies in a Nonmoral Sense, Friedrich Nietzsche (1873)

Heavy metal inherits this conflict because in order to be “heavy,” it must tackle the dark issues everyone fears. What makes these issues dark is that our normal methods cannot defeat them. We then must ask what we exclude from our methods, and we see that any anti-social information — that which might offend someone, or mention death, or suggest that morality is an imposed and artificial condition — is excluded from our methods. As a result, heavy metal becomes a kind of peering behind the curtain of an externally-imposed reality, and in seeing the horrors within, finding a new desire for both warlike apocalyptic intensity and a beauty discovered in darkness.

Romanticism re-occurs because it is generally seen as the only idea which can oppose modernism, which is like neo-classicism but even more insistent upon rationalism and the hybrid between individualism and groupthink that is utilitarianism. Metal, as a genre exploring Romanticism with a masculine and warlike approach, most closely approximates the philosophies of Nietzsche and other post-Romantic writers who wanted to escape the bureaucratic approach to society and restore a sense of adventure.

Metal is fantasy that can be applied to reality, neatly briding the two categories of art as entertainment/mimesis and art as politics. It is not protest music, nor is it the kind of wallpaper-like distracting pleasant activity that we see on most television shows. Instead, it is a manifestation of the Faustian desire for forbidden knowledge. From classical literature and music, it borrows a rigid sense of structure and a desire for resurrection, Tolkien-esque, of the ancient times of honor, blood, warfare and magic. From Romantic literature and music, it takes its major themes, including the sense of an individual trapped in a moribund society reaching out and the idea that when the individual escapes society to nature, reality can be seen for the first time. The most similar Romanticists to metal lyrics are probably the following:

If we had to summarize metal as an artistic movement, it would be fair to say it has more in common with European Romantic art than the popular music and boutique art of our present era. Like the Romantics, it sought a transcendence in accepting the world’s inequality and horror and using it as a relative opposite against which to project challenges; it wants to bring back the fighting spirit of an ancient time, and give us independent thinking and goals instead of buying us off with the humanist-materialist tripe that the mainstream media proclaims — dogma which, interestingly, has failed to solve a single widespread problem of humanity.

Even more interesting is that the genre of horror movies, an intersection of proto-science fiction and occult lore, was born of the Romantic movement. Mary Shelley, who wrote Frankenstein, was the wife of Percy Shelley, a Romantic poet. Bram Stoker’s Dracula came from the Gothic fringe of the Romantic movement as well. One of the greatest descriptions of Satan ever, Paradise Lost by John Milton, was also a Romantic work.

“I believe in tragedies…

I believe in desecration…”

The Sun No Longer Rises, Immortal (1993)

Like its Romantic forebears, metal music desires transcendence: finding the beauty in darkness by accepting the physical struggle that is life, and instead of trying to run away from that struggle into personal material comfort, accepting it as something that gives significance to our existences. Metal music desires to overcome our fear of death and of nature, and by accepting them, to show us a new world of meaning. In this, it is both a continuation of Romanticism and an evolution of it to a more coherent state.

How did this change for underground metal?

Appearing in the early 1980s, underground metal arose from a hybrid between crustcore/hardcore (Discharge) and the structuralist, neo-classical heavy metal of the previous generation (Judas Priest, Black Sabbath). It took the Romantic themes of earlier metal and made them more extreme. If underground metal has one unifying concept, it is the one emphasized by Hellhammer, “Only death is real.”

After heavy metal blew out by getting absorbed into its own popularity, and then speed metal copped out by softening its stance and sound to be more popular, underground metal roared away with pure nihilism: facing life as it is without a thought that anyone or thing in the universe cares if we collectively or individually survive. This was orthodoxy retaliating against anti-orthodoxy, which always takes the form of individuals preferring to avoid reality and so passive revenging themselves against those disciplined enough to want, in the time-honoured method of survival common to all creatures, to adapt to reality. In overcoming the anti-orthodoxy of individualism, underground metal became the first popular music genre ready to face ego-death.

The question, of course, could be asked: Why did you ever try narcotics? Why did you continue using it long enough to become an addict? You become a narcotics addict because you do not have strong motivations in any other direction. Junk wins by default.

– William S. Burroughs, Junky

Ego-death is a concept that psychedelics and zen monks alike discovered. In it, the person realizes they are one part of a giant system, and stop seeing the world through themselves. They see themselves in the world, but they see the bigger process first. Ego-death tends to lead to a transcendent state where one sees all of consciousness as a continuum, and becomes less afraid of d-y-i-n-g. Ego-death forces us to see life through a filter that is super-realistic, or dedicated to bringing people into a moment of realization that what they are touching and doing is real and they need to grasp command of their own minds to survive. It opposes panic and illusion, moral and social judgment (“knowing” from Nietzsche above), fear and pleasant unrealistic thoughts.

Not coincidentally, “only death is real” resembles topics from Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad and Paradise Lost by John Milton. In both, as in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, the protagonist is thrust into a delusional, dysfunctional, chaotic world that he alone can see is wrecked, and takes a long journey in which she or he can see that the nothingness is very real and pervades everything, and that our denial of this emptiness of life makes a greater emptiness, or a hollow illusion that cannot satisfy us. As we try to live in this illusion, we see reality peeking through, and so become neurotic.

Not coincidentally, “only death is real” resembles topics from Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad and Paradise Lost by John Milton. In both, as in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, the protagonist is thrust into a delusional, dysfunctional, chaotic world that he alone can see is wrecked, and takes a long journey in which she or he can see that the nothingness is very real and pervades everything, and that our denial of this emptiness of life makes a greater emptiness, or a hollow illusion that cannot satisfy us. As we try to live in this illusion, we see reality peeking through, and so become neurotic.

The characters in these books overcome their situations only by throwing away the rule book, avoiding what other people tell them is the truth, and acting on their animal intuition. Conrad’s protagonist Marlowe begins the book impotent and ends it with a powerful tool, like a sword or fire, to explain why what he sees is as impotent as he once was. It’s like an adolescent story, but for humanity, growing out of its moral illusion and seeing reality as a pragmatic task. In Paradise Lost, Satan is appealing but has made an error in opposing the order of nature/God, yet still he has to make this decision, to explore the world in a Promethean sense of fearlessness and self-command. His undoing is too much self and not enough command.

Underground metal recognized this duality of human thought. Official knowing was bad news; unguided knowing was chaotic and destructive; therefore, a new type of knowledge had to be created, and this knowledge was nihilistic literalism as found in hardcore punk merged with the fantasy and epic worldview of heavy metal. The political nature of punk had made it easy for foolish people to slap anarchy stickers on their rockabilly guitars and start repeating the same old stuff, like the aged activists who whine “why can’t they just see” when life has passed them by.

Underground metal was not political or social, but philosophical: it viewed the world from outside human eyes, seeing it like a large scientific experiment in which history was the result, and based its knowledge on the abrupt interruption to human illusion created by death. When we see that wisdom, we recognize that we are tiny and inconsequential, and that adapting to life is more important than the moral, social, media and political worlds made of human agreement to have a symbol stand for something.

“Only Death is Real” conveyed ego-death: no matter how big you think you are or how important, death is more real than your visions, so you must accept nothingness. To accept nothingness is to cast aside the unhealthy parts of the ego and to give it context, so that the ego is a motivic force but only one of many on a planet. To see only death as real is to wonder what else can be real. The answer is right past the end of our noses: the world is real, and it’s a continuum that renews itself, so it’s worth working for. If you like life, you work to make it better. If you hate life, you deny the reality of the world and you go further inward into the self and its desires, which has never worked for making anyone happy no matter how stupid.

We are social creatures, and it is as mathematically logical why that is so as the collaboration between parts of a computer program. We are all of the same thing, and we want to take our part in this thing, which includes nature and our fellow humans, and if we like being alive, we want to do what’s best not just for ourselves or for humanity but for the whole thing. What a stream of interesting thoughts “Only Death is Real” can unleash, in part because our society does everything it can to deny the reality of death.

The archetypal death metal bands — Hellhammer, Bathory, Slayer — all used occult imagery much as Blake, Milton and Goethe did. With that in mind, we can re-interpret Slayer’s Satanic imagery as more than being opposition to Christianity. For one, they do not seem to oppose Christianity. If anything, lyrics like “South of Heaven” or “The Final Command” illustrate, like Black Sabbath’s “War Pigs” before them, a world in the grips of evil based in power based on an illusion. In Slayer’s complex theology, Christianity is Satanic because like political strength and industry it is a false outward power when inward the person is underconfident and weak. Christianity however is seen as often accurate, in that the apocalypse does come from selfishness, and Christian morality (“bastard sons beget your cunting daughters”) is the best way to live, but a way that makes no sense in a world addicted to the power of illusion.

As in Milton, Slayer’s Satan is a rebel against a singular order encroaching upon the world, a necessary force like magnetism that opposes any such centralization. In Slayer and Milton’s view, to have any single power controlling the universe is to bring the universe toward sameness, something thermodynamicists call “entropy,” or a state when any direction yields the same results as any other because of the uniformity of the universe. Milton was edging toward a transcendental view of God as being a property of the universe, and not an ego or personality such as that overbearing one against which Satan revolts, himself a victim of his own excessive egoism.

I feel there is some hideous new force loose in the world like a creeping sickness, spreading, blighting. Remoter parts of the world seem better now, because they are less touched by it. Control, bureaucracy, regimentation, these are merely symptoms of a deeper sickness that no political or economic program can touch. What is the sickness itself?

– William S. Burroughs

In the Milton-Slayer worldview, “God” encompasses both bad and good, because together these create a reality in which we can strive for better things. Similarly, in Conrad, the tokens of good and profit are chased in such a way that they create an illusion sustained by greed, in which the only heroes are amoralists like Mr. Kurtz who use brutality and combat effectively, but are conflicted over the underlying reasoning for their goal, namely the need to produce income through ivory when greater challenges await. In the worldview these artists offer, profit motive and morality are a going-inward into the protective mantle of fear, and morality is something we impose on the world to avoid the heroic challenge of leaving that inward sanctum and achieving goals that are not justified by physical survival (morality) or material comfort (profit).

When we look at metal with these opened eyes, the sound and imagery and lyrics are far less random. Distortion is a finding of beauty in darkness, a clarity emerging not when one looks at individual grains of sound but when one hears the blurry whole and deducts from it both pure tone and the harmony of randomness to that clarity; distortion forces us to take a view from above, and see the whole picture in order to understand what occurs at any moment. It is also a metaphor for our inability to ever fully perceive the universe, telling us that if we look at the center of the distortion we will find what is occurring, even if we cannot see it perfectly. The gritty, chaotic sound of distortion defies our logical containers that look for purity and instead finds a reality that although hazy is as clear as it if were pure.

When we look at metal with these opened eyes, the sound and imagery and lyrics are far less random. Distortion is a finding of beauty in darkness, a clarity emerging not when one looks at individual grains of sound but when one hears the blurry whole and deducts from it both pure tone and the harmony of randomness to that clarity; distortion forces us to take a view from above, and see the whole picture in order to understand what occurs at any moment. It is also a metaphor for our inability to ever fully perceive the universe, telling us that if we look at the center of the distortion we will find what is occurring, even if we cannot see it perfectly. The gritty, chaotic sound of distortion defies our logical containers that look for purity and instead finds a reality that although hazy is as clear as it if were pure.

The “riff salad” of metal bands is a way of establishing that music is not a cyclic loop of verse-chorus, resembling our going inward to the world of our own thoughts and preferences, but a journey in which our inward struggle parallels our outward struggle (much like the jihads of Islam: the lesser Jihad is the war against ignorance/infidels, and the greater Jihad is the war for spiritual clarity in oneself). Metal is art because it does not preach a political solution, but shows us the reasons for it. When that sort of higher thinking fails, metal relapses to liking noise and hedonism but little else.

It is one thing to preach, as if politically, against the ego. It is another thing to show a path beyond the ego. “Only Death is Real,” like nihilism itself, is a way of dispensing with “belief” in order to begin the journey to discover what is real and what is supra-real. The supra-real is that dimension where heroism and creativity lie, where one has accepted the feared attributes of life (d-y-i-n-g, disease, sodomy) and has transcended them by seeing what is not material/tangible yet is also important. It is this journey that metal music, classical music, and all great art describes. It is starting from nothing, like Satan exiled from Heaven, and getting over resentment of life and fear of death to see the beauty in darkness and to return to life with a desire to make it better. It is a recognition of the inherent distortion of our perception, and tuning our ears and minds to see past that faltering.

When only death is real, the ego dies for a moment and we see the world as a whole, and can get out of the prison of our limited perspective and re-bond to the life that produced us and produces all we value. It is a hedonic state higher than hedonism, to love life and want to make it better through better design. This is where death metal broke from heavy metal, and it is where all thinking that rewards strong souls begins.

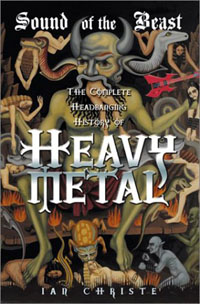

The Evolution of Black Metal

Death metal brought images of impending doom and a fascination with the macabre into a dark world. It built upon what speed metal and grindcore had already established: an apocalyptic epic where the only future was decay. Death metal incorporated the righteous integrity of speed metal and the nihilism of punk into a musical onslaught warning of destruction. It fit into Kurt Vonnegut’s famous metaphor for art: that artists are to society what canaries were to the coalminers who brought them into the depths of the mine as warnings. When the song of the canary turned weak or stopped, it meant that suffocating coal gas was flooding the mine.

Death metal is an extension of the complexity of speed metal, partially arising from the attitude of that genre that any large problem can be solved by reason. Speed metal and thrash believed in rationality, and preached insanity as a negative characteristic. Death metal became the science of understanding insanity and breakdown, not preaching against it as speed metal often did but explicating it in epic songs and vivid imagery. Black metal, as a response to the failure of death metal to avoid the crowd, was an embrace of all things destructive to human illusion: natural selection, warfare, predation, violence, cruelty and tyranny.

Black metal restored romantic side of metal as its primary vehicle; its emotion is more obvious as that is its obsession. A death metal band would never argue destruction of the world, calling it irrational, where a black metal band would call for destruction of all life on emotional grounds. Black metal’s sadness comes from its emotional entrapment in a mechanistic world, and for that reason it rebels against order, whether in Heaven, on Earth, or in Death Metal. Black metal is in many ways a return to the mission metal left when exploring the scientific mindset of the technological age (as computers revolutionized life in the eighties, quantitative rationalism experienced a resurgance of influence).

If we look at metal’s history, we can see how this conflict brewed. Black Sabbath retaliated against the hippie music of their time as unrealistic and distracting. The following generation of metal turned it into more of a party for alienated kids, which punk retaliated against by returning the focus to all the negative aspects of reality. The next generation of metal, speed metal, picked up the punk outlook but channeled it into the heroic stories of past heavy metal, creating a less lamentatory and more assertive, masculine “we can fix this” outlook. When speed metal collapsed into its own popularity, death metal returned with pure nihilism balanced by a structuralism that suggested life was understandable but denied by the individual. Grindcore rose simultaneously with death metal and restored the punk/hippie attitude of tolerance toward the individual. Black metal retaliated against this just as Black Sabbath condemned the hippies of their day by brushing aside morality for an awareness of horror and our impotence against the real threats in this world; it rejected all protest rock and literal music for a spiritual conditioning which embraced struggle, darkness, melancholy and other Romantic traits.

If we look at metal’s history, we can see how this conflict brewed. Black Sabbath retaliated against the hippie music of their time as unrealistic and distracting. The following generation of metal turned it into more of a party for alienated kids, which punk retaliated against by returning the focus to all the negative aspects of reality. The next generation of metal, speed metal, picked up the punk outlook but channeled it into the heroic stories of past heavy metal, creating a less lamentatory and more assertive, masculine “we can fix this” outlook. When speed metal collapsed into its own popularity, death metal returned with pure nihilism balanced by a structuralism that suggested life was understandable but denied by the individual. Grindcore rose simultaneously with death metal and restored the punk/hippie attitude of tolerance toward the individual. Black metal retaliated against this just as Black Sabbath condemned the hippies of their day by brushing aside morality for an awareness of horror and our impotence against the real threats in this world; it rejected all protest rock and literal music for a spiritual conditioning which embraced struggle, darkness, melancholy and other Romantic traits.

Black metal grew exponentially since its emergence as a distinct musical style in the early 1990s; previous “black metal,” from Venom through Hellhammer, had been a variant on the dominant style of the time and often indistinguishable from death metal. Like a new civilization, it grew from a small group of innovators who were disgusted by the “jogging suit” mentality: people who were essentially products of a modern time, who blindly bleated its ideas, figuring out how to play death metal and becoming popular in the genre by making their music more like what audiences accustomed to rock music expected. In essence, the crowd had infested death metal as it had speed metal before that, and black metal was a response to this.

Recognizing that no matter how they dressed up the music as something “new,” appearances could be cloned, black metal musicians decided to go where the crowd could not follow: they would write music that expressed a grandeur of nature and feral amorality, hearkening more to the values of Samurai or European knights than to the disposable ideals of modern time. Since such a topic requires music that infuses the listener with a sense of awe and beauty in the cycle of destruction and creation that renders our world, they could no longer rely on “three chords and the truth,” but had to actually put the truth in the music, and write more poetic and complex songs.

Recognizing that no matter how they dressed up the music as something “new,” appearances could be cloned, black metal musicians decided to go where the crowd could not follow: they would write music that expressed a grandeur of nature and feral amorality, hearkening more to the values of Samurai or European knights than to the disposable ideals of modern time. Since such a topic requires music that infuses the listener with a sense of awe and beauty in the cycle of destruction and creation that renders our world, they could no longer rely on “three chords and the truth,” but had to actually put the truth in the music, and write more poetic and complex songs.

The small civilization within civilization that was black metal was united more by ideals than by aesthetic or musical tenets, although all of its music by aiming to express the same kind of idea had similarities, mainly in its use of poetic complexity and truth within the music (and not necessarily the lyrics; you listen to black metal, and because of its intense artistry, find truth there). Because we are surrounded by infinite voices repeating the same few ideas in many different forms, here are the basic ideas of black metal that are distinct from the mass:

- Nature as a supreme, rational and all-pervasive order. Natural selection and an embrace of struggle took the center stage through celebration of predation and death. Even more, black metal celebrated the nature “within,” or our inner feral nihilism that made a mockery of morality.

- Anti-Christianity/Crowdism. Crowdism is the idea that respecting the will of individuals is more important than finding a realistic idea. It is a form of backward logic where we see the individual as the cause, and not the effect, of all that is around us and so convince ourselves that a human social consensual reality can override nature. Crowdism is secular Christian morality.

- Introspection. The only meaning comes from what the individual can interpret; there are no boundaries between individuals and the world (nature) as whole, but individual perception is limited to natural abilities and learning from experience. This is the opposite of the “if it feels good, do it” rhetoric of hippie rock.

- Morbidity. Viewed as an essential giver of meaning. Where most view death paranoiacally, and see it as a great entropy removing all value, black metal musicians viewed it as something giving meaning to life.

- Organicism. Like Romantic poets, black metal musicians tended to place more faith in organic growth than imposed social order. A sense of differentiation from the herd, hatred toward the incompetent and delusional, pride in unique ethnic origins and a celebration of older culture makes this a huge part of the genre.

To any student of European history or art, these values are not new; they are traditional to all Romantic forms of art, whether literature or visual art or symphonies, and were upheld by artists as disparate as William Wordsworth, Anton Bruckner, John Keats, Ludwig van Beethoven, Richard Wagner, Lord Byron and William Shakespeare. For all of these artists, nature was a higher form of order than the rules of civilization, and civilization had become decadent by praising its own “equal” order more than the “unequal” order of nature. Many philosophers, including the celebrated F.W. Nietzsche and Arthur Schopenhauer, explicated these sentiments in their own work. Black metal’s ideology is nothing new.

What was new was an expression of these ideas in popular music, because rock music and blues and all of the associated disposable art has always been a manifestation of the crowd revolt mentality: simple music so that everyone in a room could get it, diametrically opposed to the grand works of classical music which were too complex and emotionally involved for a crowd to appreciate (or even to have the attention span to endure). Rock music focuses on one emotion per song, bangs it out in riff and chorus, and makes it very simple by using a relatively fixed number of scales and chord progressions. Rock music is the perfect product because it’s easy to make, is appreciated by customers of all ages and not limited by intelligence, and is inoffensive on a certain level in that it has nothing to say that will disturb. The basic message of rock music is to include everyone equally, to appreciate them for being alive and not for their inherent traits, and to come together on simple human values and not higher ideals; rock is inclusivity. Black metal is not.

Much like when watching Lord of the Rings, Braveheart or Apocalypse Now one has a sense of an ancient warlike order, when listening to black metal one sensed a realistic and amoral entity underneath the Romanticized skin of the music. This eternal form of the human spirit grows from the naturalism of black metal as well through its belief in a karmic cycle based on natural selection. At the lowest level, humans are little more than animals. If they exert a form of natural selection upon themselves, and attempt to rise above that level, those who survive will be apt for it; if they do this for several levels, they eventually rise to a state of having a higher intelligence, degree of physical strength and beauty, and moral character (“nobility”: the ability to see what is correct for the natural order of society as a whole, and not to get distracted by personal or emotional issues). At the very top are those who are fit to lead by the nature of having a transcendent consciousness; it is thought that these much higher IQ than most modern people and were far less fearful, neurotic and self-obsessed. This, too, derived from Romanticism.

Underground metal goes mainstream

Underground metal reigned in part through its mystique. Hated by almost everyone, in and out of jail, preaching ideas which were anathema to both heads of state and hippies in the gutter, underground metal seemed a fragile and rare thing. This mystique faded as the economy shifted again, as it had done in the early 1980s allowing a rush of “indie” bands, and distribution contracts loosened up in the late 1990s.

Where once there had been “import” racks for CDs from abroad, and it was hard to find music, starting in 1997, underground metal became available in mall stores and through Amazon.com. Its identity as a separate entity became difficult to maintain, and the process of assimilation began. In response, metalheads attempted to rally around an identity as “different,” but in doing so, they focused on external aspects (distortion, imagery, indie status) instead of what did make the music distinct: it saw hope for the future in ideas outside of the same accepted dogma all the mainstream newspapers, television and radio sell to us because it is a popular product. If the truth is difficult and therefore unpopular, metal rebelled against popularity as a selection matrix, and from that developed a range of thought which made it a genre distinct from all others.

Where once there had been “import” racks for CDs from abroad, and it was hard to find music, starting in 1997, underground metal became available in mall stores and through Amazon.com. Its identity as a separate entity became difficult to maintain, and the process of assimilation began. In response, metalheads attempted to rally around an identity as “different,” but in doing so, they focused on external aspects (distortion, imagery, indie status) instead of what did make the music distinct: it saw hope for the future in ideas outside of the same accepted dogma all the mainstream newspapers, television and radio sell to us because it is a popular product. If the truth is difficult and therefore unpopular, metal rebelled against popularity as a selection matrix, and from that developed a range of thought which made it a genre distinct from all others.

Far from being alone in this, underground metal has fallen into a general trend of independent art producers seceding from reality. “Literature” has collapsed into a few thousand tiny magazines read by no one but MFA candidates in creative writing, and “visual art” has become a network of small galleries selling cute expensive paintings to uninformed patrons. Even classical music has gotten in on the decline, with “new music” — micro-symphonies of human voices, squeaking dissonant noise, and other trendy types of sound — appreciated by a diehard cult following who need a raison d’etre outside of their civil service jobs.

These genres used to speak an independent voice, but now they repeat lockstep the strange formulation of modern liberal democracy — a “neo-conservative” viewpoint which both champions civil rights and “social issues,” but also affirms the need for a strong economy and constant warfare against evil enemies. Political theorists might try to make sense of it, but it is more direct to understand it this way: popularity sells.

“One could argue that American fiction has ghettoized itself by insisting on a self-reifying view (humanist/materialist?) in which all answers are known, the political binary is carved in stone, we all have swallowed whole certain orthodoxies, and the purpose of the fiction is just to reinforce these. At the heart of this lies a selfish agenda, that has (one could arge) really ceased seeing the world as a unity, and has begun aggressively internalizing certain capitalist dogmas that say: Of course you are the most important thing, of course you exist separate from the rest of the world.”

– George Saunders, The Believer Book of Writers Talking to Writers

In this situation we find a repeated structure from metal itself, and even, larger society. Metal music goes through cycles where a new idea comes about, is looked down upon by others, and then fully expresses itself, at which point it is cloned to death by the same people who were speaking badly about it earlier (by this I mean new subgenres, not recombinations of existing genres like – eh – “nu-metal”). If you look at it as a conflict between people of able character, and those who are by nature followers, what you see is that the able create; the followers imitate, and in so doing, drown it and condemn what was created to being of the same mediocrity it helped to escape.

Indeed, the death metal of today more musically resembles rock than that of ten years ago; same with black metal. They have been assimilated, but from within the metal genre, by people whose character is so low that their highest values are to esteem what is valued by the larger society, and thus to reproduce it in the appearance of something which is not larger society, assuming that by controlling appearance, they control content. They are wrong, and they drag down everything they touch. It is this way with the creation of music, the promotion of music, and the choice of who runs hubs; most run them for the popularity, and don’t mind if there’s a whole bunch of support for moronic rock music thrown into the mix. In fact, they encourage it, as by appealing to everyone, they feel like Christ on the cross, being both a victim and a conqueror by the sheer fact of being needed.

This conflict repeats itself in all human endeavors: one group starts a process that creates benefit, and then others surge in and, not understanding the struggle of creation, parasitize it and destroy it. We can see this in the tendency of sequels to intelligent movies being junk; in the revolutions of the masses against the elites that leave nations with lower average IQs and third world levels of dysfunction; in the killing of Socrates by democratic Athens; in the denial of reality that lets Americans run up record debt, or our species to deplete fish stocks, pollute the ocean with floating plastics, and poison our open waterways with enough chemicals to turn amphibians hermaphroditic. The eternal human struggle for clarity of reality, versus withdrawing into our own perspectives and becoming oblivious, is repeated in metal and its struggle to resist assimilation.

The ‘heat-death’ of the universe is when the universe has reached a state of maximum entropy. This happens when all available energy (such as from a hot source) has moved to places of less energy (such as a colder source). Once this has happened, no more work can be extracted from the universe. Since heat ceases to flow, no more work can be acquired from heat transfer. This same kind of equilibrium state will also happen with all other forms of energy (mechanical, electrical, etc.). Since no more work can be extracted from the universe at that point, it is effectively dead, especially for the purposes of humankind.

— Andreas Birkedal-Hansen, M.A., Physics Grad Student, UC Berkeley12

With human beings, our tendency to act for ourselves alone — individualism, or selfishness — divides up our civilization and encourages entropy. Metal, as a perspective beyond the individual and the ego-drama that rock bands promote through love songs and peace dogma, encourages us instead to get over ourselves, transcend our egos, and look at reality for the potential beauty within it. In this, we enact a familiar drama to any post-agrarian-civilization art, which is that of the lone individual versus the crowd. The individual wants to do what is right, but the crowd wants him to be selfish like them, so that together they do not challenge each other and no one can ever be wrong, or face conflict, or be lonely. But in the end, the crowd always makes itself miserable because its vice is essentially cowardice. Metal reintroduces some clarity through a simple formulation: either one goes inward, and tries to know reality through oneself, or one looks outward and tries to know oneself through external opinions, and as a result, loses oneself in the crowd and its lowest common denominator inclinations, namely fear, selfishness and narcissism.

Assimilation of metal

Whether this larger conflict will be resolved is not yet certain – definitely, however, metal is a reaction against it. When people sang hippie songs, Black Sabbath brought in dark reality, and woke many out of the stupor that assumed extending democratic liberties to all humans would solve far deeper-rooted problems. As rock music headed toward an effete protest against Reagan in the 1980s, metal retaliated by condemning left and right for their ignorance of basic human dissatisfaction and the threat of nuclear warfare. Finally, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, death metal and black metal arose to remind us that we are mortal, and that there are greater values than that which society can bestow, such as nature, the upholding of tradition, and pride in our national origins.

The clones have closed in fast on those, since they are indirectly the greatest threat to clone culture to ever arise in metal. For this reason among others, it’s worth upholding in them what gave people hope: the belief that someday the war of clones versus leaders, masses versus elites, would come to an end. Some keep trying to dumb it down into a political trend that gives us a partial truth and tries to make it represent all of reality, effectively blinding us to the big picture so we can focus on a vicarious struggle:

More than three decades after Black Sabbath conjured images of the dark arts, heavy metal is growing up. The genre is increasingly incorporating social and political messages into its dense power chords.

“Metal is expanding and evolving and becoming more diverse,” said Canadian anthropologist and filmmaker Sam Dunn, who directed “Metal: A Headbanger’s Journey,” released on DVD this summer. “It’s at a much more vibrant state than it was even five or 10 years ago.”

“It’s becoming global and it’s becoming a tool for social and political commentary,” Dunn said. “It takes on a greater meaning in countries where people have had to struggle to survive. It takes on a much stronger political tone.”

Metal music in the 1980s was often homophobic and “very white,” she said, but current bands tend to be socially conscious and suspicious of political power. There’s also more women in the audience — and fronting the bands.

The lyrics on Lamb of God’s two most recent albums have been expressly political, and the politics lean heavily to the left.

Napalm Death’s Greenway is considering work as a political activist when his metal days are over, but he doesn’t think metal will ever completely stray from hedonistic and supernatural themes.

MSN

It is not surprising that mainstream media misunderstands underground metal. After all, they virtually forced its creation, since any band darker or heavier than Metallica received no recognition; the media wanted to sell us metal as party-lovin’, loud and crazy rock music. And so while the underground bloomed in 1985 to 1996, they praised stadium heavy metal and hard rock bands. During the current time, they embrace as “metal” music that is mostly emo hardcore: metalcore and nu-metal.

To an observer of the recent black metal scene, it’s tempting to get bitter. The newest style and trend appears to be “black hardcore,” or bands putting together two three-note riffs in a standard song format in recombinant order, and even the most ambitious bands are succumbing to this influence. Reminiscent of when hardcore punk music bloated itself into entropy and collapsed because no one could tell any two bands apart, this is like gangrene creeping up the legs and finally into the bloodstream of the genre.

To an observer of the recent black metal scene, it’s tempting to get bitter. The newest style and trend appears to be “black hardcore,” or bands putting together two three-note riffs in a standard song format in recombinant order, and even the most ambitious bands are succumbing to this influence. Reminiscent of when hardcore punk music bloated itself into entropy and collapsed because no one could tell any two bands apart, this is like gangrene creeping up the legs and finally into the bloodstream of the genre.

When the genre is healthiest, the winds of coming winter oppose all new bands with brutal hardship, so only the most determined make it to the stage of releasing an album. This encourages others who have talent and brains to take a stab. If a lone artist looks at a genre, and sees a thousand albums of which two are good, the conclusion will be that the genre is fattened and the fans thus unable to tell the difference between good music and bad.

If the genre seen has a handful of albums, most of which are excellent, it is instead a compelling argument for further exploration. This is how genres rise and fall, and is why hardcore punk and death metal both eventually fattened themselves into insignificance to the point that now, once you’ve heard one band, you’ve heard them all. So for the health of the genre, it’s better that fewer albums of a higher quality are released.

Ideals of assimilated metal:

- Everyone must get it. It must be simple, not challenging, and most of all not have any poetic essence to its soul, as most fans can’t get that and thus will not buy it.

- Appearance over structure. It must have a unique appearance, but say the same old things philosophically and use familiar musical ideas so that even the dumbest fans can understand it and buy it. Even more, it must be upheld as dogma truth that adding a flute or screeching spotted owl to the same old music somehow makes it “unique” and worth owning.

- Form doesn’t apply to content. In other words, appearance is more important than structure, which is the form that moulds itself to the content, in the same way a story about a rescue at sea has a different flow and arrangement than a story about contemplating death in the bathtub.

- Simplistic emotions are important. Forget the depth of “Inno A Satana”; blindly praise Satan with roaring, consistent anger, because that way every fan, even the ones with Down’s Syndrome, can get what it’s about and get into it. Start a big singular emotion party, and make it simple so everyone can buy the CD and come along.

- Everyone can participate. Black metal clones are not specific to a certain land or belief system, as they are essentially musically the same and are designed so that even a retarded outer space alien could “get it” and start tapping its feet and wearing Darkthrone-brand jogging suits immediately. Nationalism, even elitism, eugenics or belief in anything at all is out; what’s in is having some music that sounds angry, is written like punk rock, and can be appreciated by everyone so they can buy the CDs or praise the “underground” scene queens who created it.

The average black metal fan today has not heard the formative works of the genre: Immortal, Emperor, Burzum, Gorgoroth, Enslaved, Darkthrone, Beherit and Varathron when they were making essential, complex, beautiful music. All they’ve heard are the newcomers, both of the blatantly commercial Cradle of Filth variety, and the scene whore “loud, fast and antisocial” type of band. The newcomers are uniformly worthless, as they express nothing that rock music does not, and by giving it an extreme aesthetic, allow their fans to convince themselves that they are “part of” some movement against the dominant trend of society, even though much like Democrats and Republicans in America agree on the same core values, newcomer “black metal” repeats the same empty rhetoric that rock music has been feeding us for fifty years. Newcomer black metal is black metal only in the world of appearance; in terms of musical and artistic structure, it’s closer to punk rock or even Dave Matthews Band. It’s rock music.

Agents of Assimilation: The Hipster

Ever since the Allies bombed the Axis into submission, Western civilization has had a succession of counter-culture movements that have energetically challenged the status quo. Each successive decade of the post-war era has seen it smash social standards, riot and fight to revolutionize every aspect of music, art, government and civil society.

But after punk was plasticized and hip hop lost its impetus for social change, all of the formerly dominant streams of “counter-culture” have merged together. Now, one mutating, trans-Atlantic melting pot of styles, tastes and behavior has come to define the generally indefinable idea of the “Hipster.”

An artificial appropriation of different styles from different eras, the hipster represents the end of Western civilization — a culture lost in the superficiality of its past and unable to create any new meaning. Not only is it unsustainable, it is suicidal. While previous youth movements have challenged the dysfunction and decadence of their elders, today we have the “hipster” — a youth subculture that mirrors the doomed shallowness of mainstream society.

Ad Busters — Hipsters: The Dead End of Western Civilization

Adbusters doesn’t mention this, but there’s a simple pattern:

Normal, healthy people pick music they want to listen to.

Hipsters pick music to make themselves look good.

A hipster is defined by this reversed cause/effect, and this is why they parallel our society: like people looking for political handouts, they are justifying themselves to others instead of acting as they know is right.

In metal, the hipster is the person always trying to be different, to pick music that is brainy or “authentic” (simple), the person spreading trends and fads. Instead of being an authentic fan who picks the music he or she thinks is best, the hipster is using the music as adornment to conceal their ordinariness.

In metal, the hipster is the person always trying to be different, to pick music that is brainy or “authentic” (simple), the person spreading trends and fads. Instead of being an authentic fan who picks the music he or she thinks is best, the hipster is using the music as adornment to conceal their ordinariness.

What’s the damage, you ask? Hipsters bloat genres with people who don’t understand them and, in the ensuing confusion, pick the lowest common denominator. So heavy metal returns to rock, death metal returns to heavy metal, folk becomes punk, and so on.

Healthy societies work from cause to effect. We need an empire, so we build it (cause) and then it appears (effect). Dying societies work from effect to cause. We want an empire, so we create the appearance of an empire (effect) and hope it will show up (cause). This is why old black metallers fear trends, hipsters, fads and mass media like the plague: they promote this unhealthy psychology.

In the postmortem over humanity’s failure, our new reptilian overlords will discuss this issue, and conclude that humans had two modes of thought: a healthy forward-thinking one, and a negative and sick backward-thinking one. The hipster, like every other form of decay in our society, is backward thinking.

Metal is currently awash in hipsters because hipsters use something called irony to disguise their low self-esteem. If they’re listening to IRON MAIDEN, it’s because they find it amusing — not because they believe in it. In fact, they believe in nothing except what others believe in within their social group, which makes them always right. If someone makes fun of them for liking IRON MAIDEN, they can always claim their enjoyment is ironic. It’s a race to the bottom with the hipster, because believing in anything but illusion and evasion makes you a target, so they believe in nothing except “ironically,” and that’s how they infiltrated metal.

In the same way hipsters find trailer parks quaint and amusing, they found death metal and black metal intriguing. It was untamed, unsocialized material, and a threat to everything the hipster stood for. So they assimilated it, and moved in by taking positions in the community. Start buying metal, or selling metal, and others depend on you. From that they branched out by using the hipster tactic of focusing on the external. “Well, this could be more unique if we added a flute…”

In the same way hipsters find trailer parks quaint and amusing, they found death metal and black metal intriguing. It was untamed, unsocialized material, and a threat to everything the hipster stood for. So they assimilated it, and moved in by taking positions in the community. Start buying metal, or selling metal, and others depend on you. From that they branched out by using the hipster tactic of focusing on the external. “Well, this could be more unique if we added a flute…”

When you focus on the external, and don’t pay attention to the fundamental quality of music that distinguishes it, which is how well it communicates, you end up norming the music. Structurally, it becomes all the same, but externally, it’s all tricked out in motley so it appears “different” and “new.” But the real name of the game is not being different, but being the same so you are universally accepted, while having enough adornments that you stand out in a crowd… just like the hipster.

We’ve seen this steadily increasing in metal since 1994 or so, and it was helped by some in metal who would rather leave a bad legacy with a full wallet than the inverse, such as Death and Cannibal Corpse. It will reverse, but only as soon as metal bands and fans start communing on the idea of forward-logic instead of backward, negative logic.

The end result of complete cellular representation is cancer. Democracy is cancerous, and bureaus are its cancer. A bureau takes root anywhere in the state, turns malignant like the Narcotic Bureau, and grows and grows, always reproducing more of its own kind, until it chokes the host if not controlled or excised. Bureaus cannot live without a host, being true parasitic organisms. (A cooperative on the other hand can live without the state. That is the road to follow. The building up of independent units to meet needs of the people who participate in the functioning of the unit. A bureau operates on opposite principle of inventing needs to justify its existence.) Bureaucracy is wrong as a cancer, a turning away from the human evolutionary direction of infinite potentials and differentiation and independent spontaneous action, to the complete parasitism of a virus.

(It is thought that the virus is a degeneration from more complex life form. It may at one time have been capable of independent life. Now has fallen to the borderline between living and dead matter. It can exhibit living qualities only in a host, by using the life of another — the renunciation of life itself, a falling towards inorganic, inflexible machine, towards dead matter.)

Bureaus die when the structure of the state collapses. They are as helpless and unfit for independent existences as a displaced tapeworm, or a virus that has killed the host.

– William S. Burroughs, Naked Lunch

Hipsterism is reality-avoidance, in the same way Crowdism or any other mass movement is: the assimilation of the individual by the crowd in order to destroy reality, which in turn destroys the collective. Societies, genres of music, groups of friends and businesses all fit this pattern, which is fundamental to human psychology. Either the individual stands up for what is true in reality, not what the individual prefers, or the crowd declares its own reality and then the collective veers off course because it has lost touch with reality. Assimilation is a byproduct of individualism without reality, just like bad music is the product of people pandering to each other and not finding a beauty in reality, including its darkness and horror, as heavy metal has throughout its four decades.

Resisting Assimilation

The problem with combatting assimilation is that assimilation is less an act than a passive lack of acting. When good metal is not made, and people do not assert what makes metal unique, assimilation surges in like water filling the space where it was swept out of the way. Like all things in humanity, the default state is one of disorganization and failure, and it is only when wise minds step in and re-direct the chaos that prosperity of any kind happens.

We have learned what does not stop assimilation. Trying to keep the music rare means hipsters buy it on eBay. Trying to keep it indie and obscure means that hipsters only prize it more. Trying to make it more offensive or extreme just makes it more novel. These methods do not work. What also does not work is trusting a “scene” or “underground” to keep away the mainstream, because underground scenes are an advanced form of maintaining rarity through social networks.

We have learned what does not stop assimilation. Trying to keep the music rare means hipsters buy it on eBay. Trying to keep it indie and obscure means that hipsters only prize it more. Trying to make it more offensive or extreme just makes it more novel. These methods do not work. What also does not work is trusting a “scene” or “underground” to keep away the mainstream, because underground scenes are an advanced form of maintaining rarity through social networks.

A “scene” means music that is consistent enough for people not to care what band is playing, so they can socialize in the same environment time and time again. A “scene” is clubs that play music that sounds very similar time and time again so they know they can draw an audience each time. A “scene” are sellers of music who find bands that sound like each other so they can compare past successes to the next generation, getting a crop of already-proven fans to come buy it all again. The variation is dead – the conformity is absolute. And worst of all, it’s voluntary and in a moral facilitative society there are few arguments accepted against it.

That kind of consistency kills music by raising the level of expectation to an entry requirement. The hardcore “scene” murdered hardcore by making it consistent – acceptable – “fun” and extremely similar. Bands who used to fight for a living could suddenly find central places to play, sell and broadcast their music – but in order to do so, they had to make it fit within expectations. Metal will die with a scene or without some form of one.

The problem with this flood isn’t its quality in itself. The problem is that when there is a flood of undistinctive material, (a) anything that does not conform to the pattern is not recognized and (b) the information overload is so great than any excellent band that does rise will be ignored. In essence, the underground has replicated the errors made by gigantic record labels in the 1980s.

Interestingly, the same thing happened in hardcore music in the 1980s when it became cheap and easy to release seven-inch records. Suddenly, there were no “fans”: everyone had a band, zine, label or distro. Consequently, quality went down, because no leaders were picked, and a great averaging occurred. Everyone could participate, but because there was no specialized fanbase, the farthest they got was participation, getting their share. No one great rose above and therefore, the great people stopped trying. There was no direction.

Analogous to the effects of democracy and consumerism on the quality of people in society as a whole? You bet it was. Analogy to egocentricism of the west, and its own cultural failings? You bet: the same mechanism was in effect: a lack of appreciation for quality because popularity/social pressures dictated participation, an external factor, not hierarchy, which requires a measurement of amorphous qualities such as “artistic worth” which are unrecognizable to most people in the crowd. Consequently, hardcore declined to the point where, in 1985, all the bands sounded exactly the same and there were no leaders.

Analogous to the effects of democracy and consumerism on the quality of people in society as a whole? You bet it was. Analogy to egocentricism of the west, and its own cultural failings? You bet: the same mechanism was in effect: a lack of appreciation for quality because popularity/social pressures dictated participation, an external factor, not hierarchy, which requires a measurement of amorphous qualities such as “artistic worth” which are unrecognizable to most people in the crowd. Consequently, hardcore declined to the point where, in 1985, all the bands sounded exactly the same and there were no leaders.

Another concept, that perhaps will embitter some because of its practicality, is that of your personal landfill. What you produce on compact disc or vinyl or tape doesn’t magically disappear. It ends up in the landfills, with all the other waste you produce, to rot in insignificance, slowly leeching poisons into the earth. You like being alive, right, or you’d be dead — why create more personal landfill if it won’t achieve something you desire? For every CD you buy, there’s one more CD in that landfill. Buy the best, ignore the rest, and your personal landfill will not only be small, but will possibly not exist as others enjoy those CDs, since good CDs can be enjoyed in any age while trends are temporal.

My suggestion to all those who love metal is simple: stop supporting bands that are OK instead of great.

Few genres demand as much long-term allegiance as metal, and get it. Of styles likely found in a record store, only metal, industrial, country, jazz and classical have enduring audiences. Other genres are bigger, but people stay with them for fewer years. As history has shown us, metal is too easily absorbed by the mainstream. Black metal selling out and the rise of nu-metal occurred at the same time – is anything in the universe “coincidental”? It’s interesting to note that a similar absorption afflicted death metal, heavy metal and hardcore punk, all of whom relied on popular-music-style short song formats.

The Case for Metal to Follow Classical

However, there is one guaranteed way to take metal out of the mainstream: leave behind the mainstream song format. Most songs are three minutes of a verse-chorus nature, and they use devices such as rhythmic predictability on the offbeat (“expectation”) and melodic hooks. If metal were to expand on its riff salad nature, it would join genres like jazz and classical in a musically distinct form, and become inaccessible to those who want to make or consume bite-sized music. Every other metal band aspires to classical guitar anyway; why not liberate our impulses toward something that is clearly enjoyed and valued?

For example, consider these micro-symphonies:

When people tell you what they want, they usually tell you what appearance or experience they want — the effect — and do not understand the device for achieving that effect — the cause. They think in terms of the appearance of what they want and not the underlying structure.

For example, when people say they want simplicity, what they really want is organization. It’s why “My Journey to the Stars” works even though it’s “complex” in theory — complex means having a central idea that is simple and clear, and then manifesting it in different forms so people can compare them like metaphors and see the abstraction. People will tell you they want raw, fast, brutal, simple but they’re talking about the one riff they remember, kind of how most people can identify the opening riff to Beethoven’s Symphony Number 5 — it’s the simplest, most memorable part of a complex music experience.

The role of art is to be a silent philosopher, meaning that it does not make explicit commands and references to everyday objects, but gives us a clear spiritual commandment and its corresponding aesthetic from which to work. Art organizes our spirits and approach to reality. It is important that art does this because most people know the end result they’d like to see, but are completely unaware of the context in which it exists. They see a riff, and figure that if they just heard that riff, they’d have the whole experience, or they think of one moment when they were happy and assume that correlations which occurred simultaneously to that moment — a cigarette, a postcard, a summer day — are the cause when the real cause was the sequence of events that led up to that one moment having great significance, or that one cigarette being the break that really helped them find mental clarity. It wasn’t the cigarette — it was the context.