People do not realize that our society is in the midst of a war. A memetic war, in which one ideology will win out over the other. As we see time and time again, the different worldviews are entirely incompatible, causing the type of internal conflict that destroys empires.

Heavy metal is caught in the middle of this. Those who want to push their ideology on you have discovered it, and try to use it as a “blank slate” on which to write their messages. We found out in the 1980s that Christians did this, in the 1990s that the far-right tried, and now in the 2010s, that an echo chamber of “social justice” agitators wants to use metal as its personal billboard. Mainstream metal media — staffed mostly by such people — agrees with them. The variety of hipster known as SJWs are hoping to take over metal and use it for their own ends.

As Old Disgruntled Bastard writes:

The modern state of metal writing, as is the case with much of modern metal, has to do with the wrong kind of people being attracted to the music. Those who don’t identify metal with a higher ideal will only think of this subject as so much faffing and will continue drowning themselves in anodyne cliches, self-referential and flippant by turn. Worse yet, in a show of incredible egotism, they will expect the music to fall in line with whatever personal agenda they might be touting at that moment. It speaks of a stunted, unadventurous, and dishonest bent of mind to outright dismiss ideas that may be pariah to our own and then to run down, ad hominem, those that dare think differently.

He hits on a vital point: their goal is not to crusade against a specific evil, but to eliminate everyone who does not dedicate their life to advancing the same agenda the SJWs do. As many people have pointed out, SJWs are a bit hypocritical. They whine about injustices to women and minorities, but night after night they are in front of their computers, putting other people down instead of working in the ghettos or middle east where women are being raped and executed en masse.

This reveals the agenda of SJWs, while it surely overlaps with their left-wing political views and hipster lifestyles in which activism is ironic and fresh, is actually to make themselves appear to superior to others. SJWs are the new master race, in their own minds. By day, they are cubicle drudges with unimportant jobs who live in expensive city apartments and spend themselves into debt buying organic free-trade wine and artisanal wall hangings. By night, they are transformed into warriors, heroes, Anne Franks and Mother Theresas combined. They find their importance in “social justice” because it allows them to pretend they are better than other people, and to experience the delicious revengeful joy of forcing others to be silent and apologize. That is the thrill of SJW: subjugating others with words from the comfort of your computer, with a glass of Malaysian Anisette Merlot and a rare live Deerhoof set on the radio.

What obstructs them is the very fact that metal is not a blank slate. It has its own beliefs, which deal with the world and its problems from an entirely different angle than SJW solutions do. Its basic rule, non-conformity with society for the purpose of discovering the raw unfiltered power of nature and truth, opposes the very notion of collective action for some slogan or political issue. Metal is against politics itself. It sees politics as an outgrowth of social thinking, not an end in itself. In the metal world, politics is a distraction and SJWs are more nagging nannies who distract us from the real problems. As MetalReviews writes:

Let’s lay it down as law, if in the confines of this editorial only: Black Metal ist krieg, waging war on all, and Black Metal that isn’t krieg, that doesn’t wage war on man, god, musical boundaries and every living creature whatever colour or creed isn’t proper Black Metal – there’s more spiritual closeness between Transilvanian Hunger and La Masquerade Infernale, between De Mysteriis Dom Sathanas and 666 International than there is with something like Panopticon’s Collapse or Eldrig’s Mysterion. They may all be great albums, but the spiritual difference is greater than that of the music itself – Arcturus and Dødheimsgard are no more trying to convert you to Anarchism or Ariosophy than Darkthrone and Mayhem are.

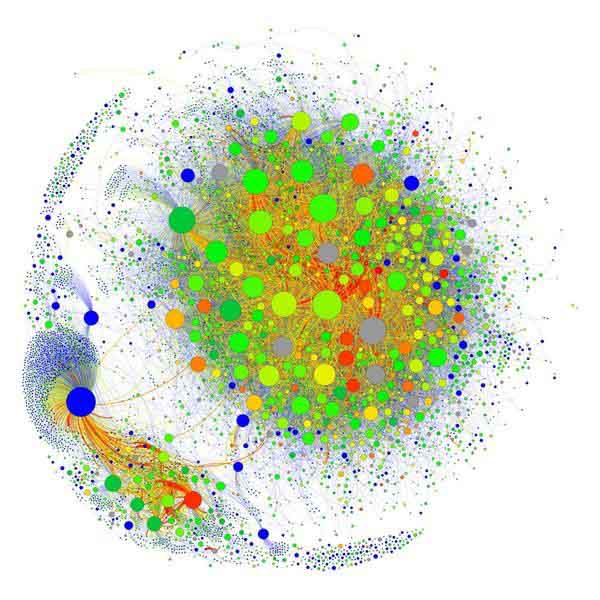

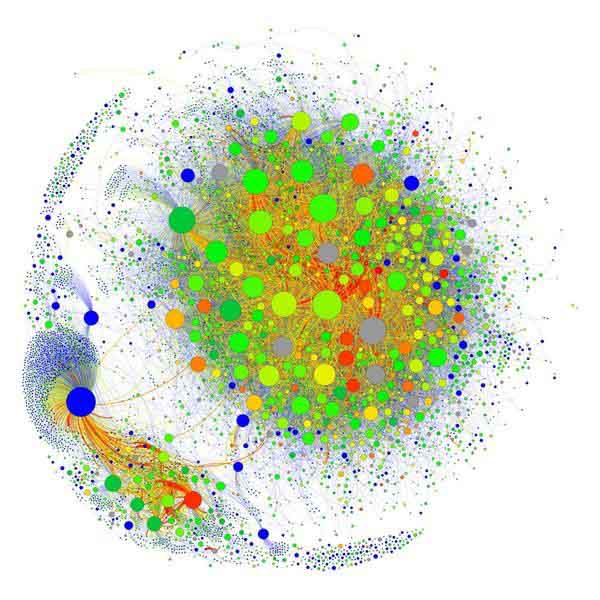

Metal has a culture of its own. SJWs are attempting to genocide that culture and replace it with the watered-down indie rock to which metal riffs have been added that the mainstream media media have been pimping for some time. They achieve this by coordinating among themselves. Someone once plotted the communications between two groups, GamerGate and its opposition. The opposition show a trend toward conformity, where GamerGate was more chaotic and open. The SJWs of today were the authoritarians and Nazis of yesterday. A short demonstration follows.

Krieg frontman Neil Jameson — who like Decibel editor Albert Mudrian unfriended our previous Editor on Facebook for what can only be assumed to be political reasons — recently wrote a piece in which he opines on the condition of women in metal. Like most SJW articles, it begins with a justification for its demands on your attention, and threatens you with guilt:

I recently realized that I’ve been having more and more discussions with people about how women are treated within the metal scene, and music in general. Turns out my knee-jerk reaction to throw jokes at the problem wasn’t the best way to address it. This goes a lot deeper, and regardless of how it may make people uncomfortable, it’s a discourse we need to have—and keep having—because the problem isn’t going away; in fact, it’s getting worse.

This is politician-speak like might be used for the wars on terror, drugs or drunk-driving. There’s this problem, see, and it requires immediate attention. Not only that, but it’s getting worse the more we just sit here. Leap into action right now and do whatever I tell you! He goes on from there to make his big point:

As a man, I’ve never gone to a show worried that someone was going to grab my dick or give me a drink with some bullshit drug in it. It’s not because I don’t think I’m pretty; it’s because this is shit that doesn’t happen to men (I understand someone in the comments section will have a story saying that it does, but for the sake of argument, please shut the fuck up). It’s just not something we have to worry about. Women have to shrug this behavior off because they’re afraid if they speak up that it’s going to be turned around on them due to what they’re wearing, or their sexual history, or the simple fucking reason they have a vagina and guys are taught from a young age through marketing and media that we’re entitled to that. Movies and other forms of storytelling glamorize women going to shows to fuck and nothing else. The idea that they’re there because they love the music seems as absurd as a cop telling the truth during a trial.

In addition to the type of terrible writing that thinks throwing in the word “fucking” for unnecessary emphasis somehow makes it edgy, this piece shows us a lot of guilt — and no facts. We all know that there are some badly behaved people at shows, and their bad behavior takes many forms. People throwing beers, pulling non-participants into the pit, fighting with bouncers, or just being general doofuses are common enough, but not accepted nor the norm. In my experience, metalheads have generally stood up for personal boundaries to anyone transgressing them, without checking to see if the victim was a white male first. But in the Jameson piece, the rambling story goes on with reasoning about how we should stop everything to fight a problem he supposes is somehow very serious, despite no assessment of how wide of a problem this is or even whether it is a problem with metal or simply dickheads being dickheads at rock shows.

But really, the plight of women in metal is not the point. The point is that Jameson has joined the SJWs and wants their approval so he can sell them the “new” version of Krieg, which takes pride in being “open-minded,” a term that means not metal if you analyze it. As he says himself:

“We were one of the first geographical groups to really tie in non–black metal inspiration, like my covers of the Velvet Underground/The Stooges, etc., Leviathan/Lurker of Chalice’s Joy Division and Black Flag influences and covers, Nachtmystium’s interest in psychedelics and more blues-based ideas, etc.”

In other words, innovation by devolution. These bands are much older than metal and fit more into the rock paradigm than metal has. This is like stepping backward a generation and claiming “progress” as a result. Why would he pick this approach? In the SJW world, metal is bad and anything that pretends to be metal but is not is good. Therefore, bands that claim to be innovators for re-hashing older genres — which most metalheads want to escape — are to be praised, and anyone who makes metal for metal’s sake is bad and should be avoided. They need this argument to advance the illusion that metal is a blank slate, instead of the vibrant culture that it is.

What else might Jameson be doing here? Others have defined this pathology before:

A gaming term used to describe a male gamer who, in a desperate attempt to get himself laid, will attempt to woo or impress any female gamer he comes across online by being overly defensive of her and giving her special attention, such as playing as a healing class and only healing her.

That is White Knighting. In other words, men who publicly proclaim themselves sensitive to women’s issues are doing it to get laid or be accepted by a new social group. You may remember this from high school or college. At the mid-point of freshmen year, guys figure out that they can attend feminist workshops, get misty-eyed about how oppressive they are, and go home with a new girl each night. This has little to do with ideology and everything to do with human behavior. People who want acceptance into a group will memorize and repeat the appropriate chants to get what they want.

Is this what the former Lord Imperial, now short-haired Neil Jameson of The Velvet Krieg is doing? Let’s look at some of his statements from the past.

Wikipedia recalls an interview by Jameson in which he expressed a different viewpoint. Although the Wikipedia article was edited mysteriously (moderator notes: “Unexplained removal of content”) on July 5, 2013 at about the time Jameson started writing for Decibel, it can be found at the Project Gutenberg wiki. Jameson — who had just gotten out of his band Weltmacht which had pro-Nazi themes, even getting signed to pro-far-right label No Colours — was heading in an entirely different direction just seven years ago:

Krieg were boycotted in Switzerland “because I freely use offensive words like ‘nigger’ in regards to the disgusting double standards and politically correct nonsense that has spread through the world black metal scene. This is a scene that encourages violence and hatred, but if you say something against anyone besides Christians it sends a lot of people into crying fits. There was one person who wrote me saying he didn’t approve of my life ‘affirmation’ on the Satanic Warmaster split in which I, I felt very blatantly, criticised both the life loving movements and the politically correct movements, but I guess these people are too fucking involved in down syndrome to notice IRONY. Well fuck them, I don’t want the support of people who cannot read the entire idea, but rather pick at ‘dangerous’ words. When the fuck did this stupid concern for hurting people’s feelings become an issue in black metal? […] ALL PEOPLE ARE SHIT […]. As for Switzerland, we got banned from the country for using ‘nigger’ on this 7 inch, which as I stated before, was anti political correctness, NOT PRO FACIST.” Imperial added that “[u]nderneath the abrasive offensiveness lies a much greater meaning that many would take the time to inspect and study. Beneath such a bitter shell lies enlightenment. IF you can fight through my venom, then you will find truly what I am spreading through the words of Krieg.”

This viewpoints sounds like those in GamerGate and MetalGate, except that we do not use racial slurs to denigrate other groups to make our points. We just speak up for what is true against the onslaught of SJWs. Jameson’s case is probably quite normal; he has simply joined the hive mind so that he can meet more people, be cool with the other SJWs at Decibel, and advance his own career, in defiance of the heavy metal genre he once found inspiration in. In other words, SJWs in metal are simply another form of selling out and assimilation into the mainstream herd.

11 CommentsTags: albert mudrian, blank slate, gamergate, krieg, metalgate, neil jameson, racism, sjws