We are fortunate to have Ian Christe, metal journalist and Bazillion Points editor/publisher, to join us for an interview. He has authored literally hundreds of articles on heavy metal music and several books, covering topics from death metal to Van Halen. Much of his writing studies emerging technology and underground cultures, which makes him a fit for the interviewers as well. We were lucky to catch him at the Chatsubo bar in Chiba City, Japan, for a few words about metal and the state of journalism about it.

You’ve been involved in metal and music in multiple ways for some time. How did you get into metal, and how have you been involved — books, zines, bands — with the genre?

I was thinking about this recently — I’m only moderately old now, but because I got into metal when I was extremely young I remember all this truly ancient history. During junior high school, I lived with my mom in Germany, and when I was 11-12 years old I was using my lunch money to buy Iron Maiden singles, Accept, Motorhead, Judas Priest, and Black Sabbath records. To put it in perspective, when I bought Scorpions’ Virgin Killer, with the kinky pedo cover, the high school aged girl in the photo seemed way older than me. We came back to the States in 1983, when I was 13, and I started doing radio shows at WEOS in Geneva, NY, playing Venom, Anvil, Mercyful Fate, Slayer, Voivod, and lots of lost obscure bands like Thrust, Armed Forces, and Witchkiller. That’s way upstate, but Manowar hails from there, and Metallica and Anthrax had just recorded their debut albums in that area. It was definitely a metal hotbed. I got plugged into the underground through that, bought some Nasty Savage and Hirax demos, and advertised my show in ‘zines like the great Kick*Ass Monthly.

We moved to Indiana in 1985, and it was culture shock. I had long hair, wore a bullet belt, and listened to Destruction, and suddenly I was surrounded by kids unaware of anything beyond Motley Crue and Aerosmith. So out of necessity I got into tape trading, and got into intense bands like Voor, Cryptic Slaughter, Genocide/Repulsion, and of course Death. I skipped school in the spring of 1986 to go see Metallica opening for Ozzy Osbourne, the big moment for underground metal going mainstream, and ended up spending the afternoon goofing around with Cliff, Kirk, and James from Metallica, and also everybody in Samhain except Glenn Danzig. Those two factions were a mutual admiration society, and I was supercharged to be in the middle of it all. I was inspired to start a fanzine after that, IAN Mag, which I titled after myself so I could cash the checks. That lasted through 1988.

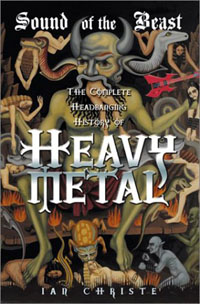

I don’t mean to ramble on about all this archaic stuff, but everything I’m talking about is the basis for what I’m still doing as a mature, respectable, gone-legit headbanger. I was basically on a metal mission for the entire 1980s. In the 1990s, I got into different things, learned about the world, and developed as a writer by working in DC, New York, and freelancing for magazines like Wired, Spin, and so on. When it came time to write Sound of the Beast, I fused the professional side to the passion for metal. In fact, I remember my proposal for the book came with a stack of clips that started with the New York Times and ended with an old letter from Dave Mustaine.

As far as music goes, I’ve had a string of very fulfilling projects of every kind ranging from bluegrass to Glenn Branca’s guitar army. I’ve toured Europe and South America performing a kind of musique concrete with a modern dance company. So all of that came together in the crazy Dark Noerd the Beholder dark technology metal project — which sounded pretty bizarre and extreme in 1996.

What prompted your move to self-publication with Bazillion points?

Frustration in two forms. Selfishly, after working with two giant publishing houses, I was very discouraged with the corporate approach to making books. You know, it takes three months to get approval for a tiny text change on the cover, and there’s just no sensitivity for how to customize any aspect of production. With Sound of the Beast, at least I was very lucky to have an editor who was only too happy to put me in touch with the art department or promotions. He got the work off his desk, and I got to have some input, which is rare for an author. Then secondly, it’s frustrating that people like Daniel Ekeroth, Jon “Metalion” Kristiansen, or Jeff Wagner, all hugely respected in their areas of expertise, could never have a hope in hell of getting a mainstream book deal. Well, I realized I could stop complaining and do something about it. Viva Bazillion Points!

Would a DIY book publishing house such as yours have been possible 10-15 years ago?

I don’t know, I definitely wasn’t capable of figuring that out. I have to say it was possible, based on the inspiring successes in the early 90s of classic punk imprints like Henry Rollins’ 2.13.61 and Adam Parfrey’s Feral House Books. But I didn’t have the experience. And the rich earth of unpublished metal books needed time to ferment, too!

What segment of the metal audience or population in general have you seen as the most excited to read the types of books you are publishing?

I can’t answer that yet — a wider audience than you’d expect has responded to Daniel’s Swedish Death Metal book. Though the bands are pretty obscure, the experience of getting caught up in a movement he describes is universal. I couldn’t believe that Publishers Weekly gave Swedish Death Metal a starred review, and made the book its web pick of the week. In three months, Andy McCoy’s book will be out, and then I can tell you how death metal books fare compared to gypsy vagabond rock guitarist memoirs. I think the common trait of Bazillion Points books is that while they’re each very specific, they’re also very good, which is pretty exciting in itself.

Do you find metalheads to be an especially literate segment of the general population?

I don’t think metalheads consider themselves bookish, but yes I think out of necessity metalheads are rabid readers. It’s always been that way, because printed media, email, and web sites are the main lines of communication. There’s very little radio and no television exposure for metal, so metalheads end up reading countless pages of text every day to stay in touch. And metalheads can be very curious creatures — if Ulver makes a record based on John Milton’s Paradise Lost, a lot of fans will go read the book. So the end result is yes, so far Bazillion Points is succeeding because metalheads are thoughtful, thorough readers who appreciate high-quality books about things they care about that they can’t get anywhere else.

If there is in fact, a heaven and a hell, all we know for sure is that hell will be a viciously overcrowded version of Phoenix — a clean well lighted place full of sunshine and bromides and fast cars where almost everybody seems vaguely happy, except those who know in their hearts what is missing… And being driven slowly and quietly into the kind of terminal craziness that comes with finally understanding that the one thing you want is not there.

– Hunter S. Thompson, Gonzo Papers, Vol. 2: Generation of Swine: Tales of Shame and Degradation in the ’80s (1988)

The rock biography, as it is most commonly understood, is given more to sensationalism rather than “analysis” or sometimes anything even remotely musical. You’ve taken on these types of bios with Bazillion Points, including the Van Halen book and the upcoming one featuring Hanoi Rocks. Do you feel what you are presenting differs from this description, if it even matters? Is your viewpoint more coherent with how metal music views itself, or in your eyes should be viewed?

With Van Halen I was mostly interested in deconstructing the personalities and breaking down the key events of the band’s story into manageable, human-sized events. If Van Halen in their prime in 1984 seems impossibly gigantic, I wanted to show all the tiny steps and late nights of practicing that led up to that. It’s meant to humanize guys like David Lee Roth and Eddie Van Halen who are usually viewed on a pedestal. Andy McCoy’s book is different because he wrote it himself, and so you get to see life through his eyes. Very entertaining. And yes, I’d say my viewpoint is pretty consistent with metal’s values at least — honesty above all, fearlessness right behind.

What makes a specific musical personality even worthy of biographical depiction in the first place?

Public fascination — but that’s a chicken or egg answer, isn’t it?

Rock music is generally written about by insiders and ignored by cultural historians, and so tends to have an insular viewpoint. Since metal came from rock, it is analyzed by the same template. How does this work to describe a genre like metal that seems to want to break away from mainstream rock?

I try to have an inside-outside approach. Writing about the nitty-gritty details from the trenches, reaching out to an audience that doesn’t even realize there’s a war going on. I believe metal has universal appeal — it’s not for everybody, but within every family, clan, or social group in the world I guarantee there are people predisposed to be drawn to the flame. It’s a kind of universal elite, I guess.

You have on several occasions lambasted the use of genre-descriptive terms. However, when we speak of genres like death metal and black metal, we could be describing artistic movements that share among themselves values and methods that differ from similar “sounding” genres. Do these subgenre terms have validity in your view, and what are the limits of this validity?

I don’t think genres should be taken too seriously, and I don’t respect bands who strive to be total slaves to a pre-existing genre and its rules. But yes, the genre descriptions themselves are extremely helpful, and I’m proud that metal has spawned and cultivated so many variants over the decades. And for instance on my Sirius Radio show Bloody Roots, I’ve been picking apart different genres every week for almost five years now, so genres are very much a part of how I think about metal. But I’ll also say that with most so-called subgenres, you’re usually talking about attempts to mimic the music of one or two extraordinary bands. Like with black metal, Bathory. With thrash, Exodus. And so on.

Like rock, metal can be insular. Does it have validity as an artistic movement, and what does it contribute to culture at large? Do you view it as counter-cultural, sub-cultural or counter-counter-cultural, or some mix of the above?

Well, that’s a subject for a book in itself. It’s a form of revolution that’s widely available for a few bucks at every Wal*Mart. It’s distrustful of change, but willing to take huge risks. Metal’s fascinating still. I guess I’d consider it a vast subculture, but not really a counter-culture. Like I said in Sound of the Beast, it’s “a quest for truth in a storm of folly.”

In Sound of the Beast you took on the arduous task of compiling nearly 40 years of worldwide music history into a comprehensive volume. How much have you been itching to revisit and update it since then, and what would you like to change?

I started writing in 1999, so I’d like to thicken the 1990s years tremendously, and then explore the rebirth of metal in the 2000s. I’ve also interviewed Ronnie Dio, Rob Halford, Tony Iommi, and the Scorpions about the 1950s and 1960s, and I’d like to get some of that material out. The book is still timely, and not many of my opinions have changed. But there’s so much more ground to cover now.

Was “objectivity” a concern when you were writing Sound of the Beast, or any of your other books for that matter?

Sound of the Beast was very much a work of advocacy, to grab and secure heavy metal’s place on bookstore shelves. I was very conscious of giving a voice to the millions of fans who had supported tens of thousands of bands over dozens of years. Without losing a critical edge, it was very important to me to state the case for why metal matters, and I’m humbled and honored to say that I think the book succeeded in all those aims.

The contemporary American may have failed, like his predecessors, to establish any sort of common life, but the integrating tendencies of modern industrial society have at the same time undermined his ‘isolation.’ Having surrendered most of his technical skills to the corporation, he can no longer provide for his material needs. As the family loses not only its productive functions but many of its reproductive functions as well, men and women no longer manage even to raise their children without the help of certified experts. The atrophy of older traditions of self-help has eroded everyday competence, in one area after another, and has made the individual dependent on the state, the corporation, and other bureaucracies.

Narcissism represents the psychological dimension of this dependence. Notwithstanding his occasional illusions of omnipotence, the narcissist depends on other to validate his self-esteem. He cannot live without an admiring audience, His apparent freedom from family ties and institutional constraints does not free him to stand alone or to glory in his individuality. On the contrary, it contributes to his insecurity, which he can overcome only by seeing his ‘grandiose self’ relfected in the attentions of others, or by attaching himself tot those who radiate celebrity, power and charisma. For the narcissist, the world is a mirror, whereas the rugged individualist saw it as an empty wilderness to be shaped to his own design.

– Christopher Lasch, The Culture of Narcissism (1979)

What has been the most common criticism of your writing to date, and to what degree do you take such criticism into account?

The most common criticism of Sound of the Beast is definitely that there’s too Metallica. I needed a central character for the non-initiated readers, and as the biggest metal band ever by far, they became the common thread. But it pisses me off when people falsely claim that Metallica gets a polish job in the book — their missteps are savagely underlined, and I think about halfway through it’s plainly stated that in the 1990s they were no longer a metal band, but a rock band. Plus the one single negative reaction I got from anybody covered in Sound of the Beast was an angry phone call from Jason Newsted, so I guess he wasn’t thrilled with his moment in the sun. Some critics said the book was too positive about metal, but I sure don’t care what metal haters want to see in a metal book.

What is your opinion on the books on metal (and conclusions drawn in them) written by academics/outsiders, particularly sociologists like Deena Weinstein (Heavy Metal: The Music and Its Culture) and Natalie Purcell (Death Metal Music: The Politics and Passion of a Subculture)?

I appreciate the process and legitimacy of Deena Weinstein’s book, but it’s impossible to create a sociological overview of heavy metal as a phenomenon. Heavy metal fans reflect their surroundings, wherever you go. In a blue collar area, you get blue collar fans. In Queens, NY, you get Asians, Latinos, and blacks at shows. In Dubai, you get rich kids. I like what Katherine Ludwig says in Sound of the Beast about these generalizations: how can you classify metalhead teens as cola-chugging NASCAR fans when that basically sounds like a description of the majority of Americans? So I say the function of metal varies by country, region, and many other factors.

You recently appeared in Time Out New York and received a pretty favorable portrayal. How much have you seen metal crossing over into the indie/art scene over the years?

You recently appeared in Time Out New York and received a pretty favorable portrayal. How much have you seen metal crossing over into the indie/art scene over the years?

In recent years, I think the indie scene has been completely infected by metal. If Thurston Moore from Sonic Youth is still any kind of bellweather, he’s lately been singing the praises of Beherit — and Daniel’s Swedish Death Metal book! Fair enough, Sonic Youth influenced Napalm Death and Entombed, after all. But yeah, that Time Out profile is extremely favorable. Another humbling indication that Bazillion Points was a good idea.

What does the common characterization of metal as “violent entertainment” (akin to comic books, horror/gore movies, and true crime novels) mean to you? Are there similarities between these genres, and does this point to artistic motivations in common?

As somebody who watches an extremely violent movie pretty much every day, I think there’s a small but important difference. Metal is fascinated with war, murder, nuclear bombs, rabid dogs, and she-demons because these are all things that no society or moral code can fully explain. So all these great metal songs are small meditations on the thrills and fears of the unknown. Movies tend to take those fears and use them against you! Again — this question is another small book in itself, and I’ve already been blabbering for an hour.

How should publishers (rather than authors) be treated where controversial or questionable works are disseminated?

Only as a publisher, I’ve come to fully appreciate how much the United States protects and values freedom of the press. I know the situation is a lot different in Britain and Germany, not to mention Iran — although my friend Mahyar Dean has written books about Death and Testament in Farsi. But so far I’m happy to say I don’t have any experience with controversy. Books with giant upsidedown crosses on the cover filled with stories of underage drinking, mayhem, and teen suicide? No problems here!

You seem to have some intimate experience with New York death metal from back in the day. Have you considered writing a book on that scene similar in scope to the Daniel Ekeroth book you recently released?

No, it’s not true, I moved to New York in 1992 and for the first couple years was more interested in seeing avant garde music like Swans, Naked City, Borbetomagus, Boredoms, Sun City Girls, and Caroliner. But starting in 1994, when metal went back underground, I saw hundreds of amazing shows in New York in tiny venues, some of my best mindblowing experiences. Still, I’ll leave the epic NYDM history for Will Rahmer to write — but I’ll definitely publish it!

The Edge… There is no honest way to explain it because the only people who really know where it is are the ones who have gone over. The others- the living – are those who pushed their luck as far as they felt they could handle it, and then pulled back, or slowed down, or did whatever they had to when it came time to choose between Now and Later. But the edge is still Out there. Or maybe it’s In. The association of motorcycles with LSD is no accident of publicity. They are both a means to an end, to the place of definitions.

– Hunter S. Thompson, Hell’s Angels (1966)

Visit Ian Christe, his books and the books he publishes at:

www.bazillionpoints.com