Recently the word got out about a new book that’s going to explain the metal underground. This book, called Underground Never Dies, is edited by Andrés Padilla, the longstanding publisher and chief writer of Grinder Magazine.

Like several underground books before it, Underground Never Dies does not attempt to summarize the underground from a single point of view. Rather, it lets many different voices speak and, like harmonization in song, a truth emerges.

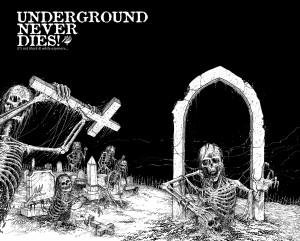

Cover art by Mark Riddick graces the entrance to this all-star production of underground metal analysis and opinion. In these pages, you will find people that you know of, or will want to know of, who helped build the underground into what it is.

We were lucky to get a chat in with Andrés as he prepares to launch this challenging work. Thanks to Andrés Padilla, Grinder Magazine and Doomentia Records for helping us secure this interview.

The most difficult question first (sorry!): what is the “underground”?

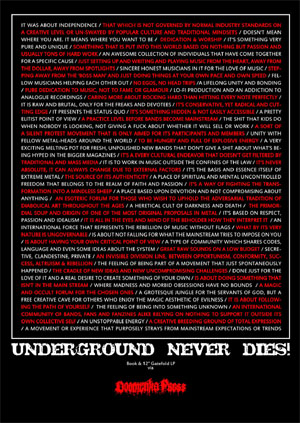

From a Thrasher’s point of view, it’s a very particular phenomenon developed in the early eighties when the roar and corrosion of Metal began to sprout all over the world. Ignoring rules, norms and standards, this trend and way of thinking opened up its way in a pure, honest and caring manner. Personally, the underground has been the path I have followed all my life, not only musically (I also listen to other music styles) but also in the type of life and philosophy to follow. Since the metal stench entered my blood it has never left. On the contrary, it has grown and strengthened my vision for this movement that in spite of any dogma, represents a way of life not only for me, but for many other devoted followers of this sound, which becomes my daily sustenance.

Underground is devotion and commitment; it is to follow your own path, not accepting the mainstream as your food, rejecting the rules of the religion – Christianity , impose your own voice, make your mark, teach others that way which means to believe in yourself. It’s a “fuck you” to the system.

Musically it is the opposite to the establishment. This is where the mind has a space to open freely and go with the corrosive and distressing death metal sound, which in my case is my favorite style.

It may have been born in the eighties, but not everyone who was there at the beginning has continued its traditions. I feel lucky to have never given up this way of life and even to this day, have supported its development and growth, either by editing a fanzine for 25 years as well editing and distributing discs and demo tapes. Although the rise of the Internet has dramatically changed the way it’s distributed and spread out, the underground has mutated over time, trying to keep his old philosophy and aesthetics. Long life to Death Metal!

How did the idea of this book come to you, and how did you embark on the course to write it and publish it?

Before finishing school I started to make my own fanzine. Up to this day I continue, sending letters, talking with underground bands, exchanging demos/CDs/LPs/videos etc. has been my way of life. I never wanted to look for a job in an office. Metal has been my best ally and daily food since I started listening to it in the mid eighties.

So if you ask me how I got this idea, well, it just came to me, I never looked for it! Everything came naturally. I like thriving, without losing its philosophy, and after 25 years doing fanzines, I wanted to do something more challenging, something that defined a little better what my life linked to music has been like, even if it’s been behind a desk. I’ve always believed that nothing is impossible, only death is unavoidable.

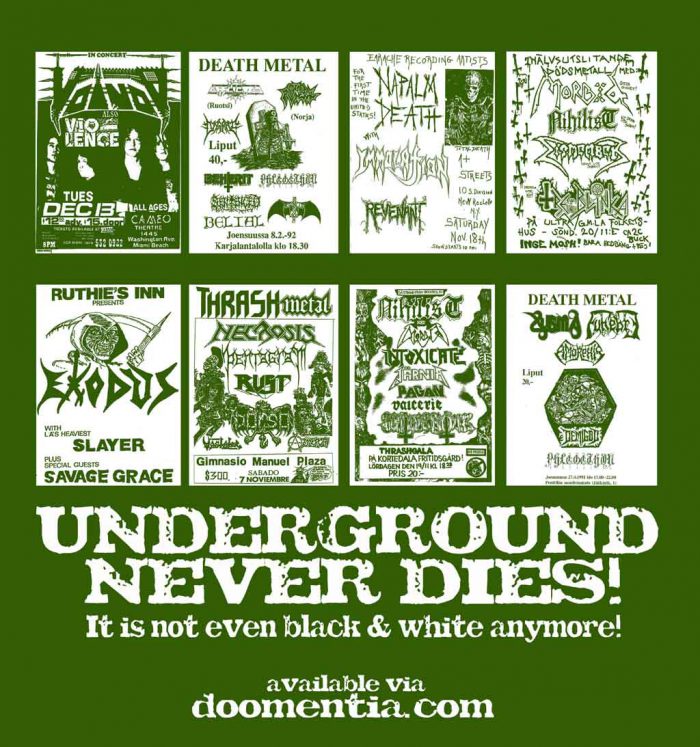

Then, as there is no worldwide publication that has managed to piece together an overall concept about this repulsive and dark phenomenon, I wanted to be the first madman to embrace every corner of the planet and display it in a book with a ton of posters, photos and comments that may finally tell, what, how and when all this happened. Underground Never Dies is just that, an incredible journey into the past where you can explicitly revive what was a unique time.

About the way it’s going to be published, maybe it was fate or luck that made me send a copy of my first book — Retrospectiva al Metal Chileno 1983-1993 — to Doomentia. Lukas (founder) loved my work and when I told him I was doing a new book about the worldwide Underground, and in English, he gladly accepted to publish it.

Do you think “underground” (perhaps like “outsider”) is a cultural identity more than a marketing category?

Absolutely, at least for me. I am very different from other normal people who wake up every day to go to an office or accept system standards. So this phenomenon for me has its own identity, and even though throughout its developmental years many people have left to take on another identity, I know that we are thousands who still believe that this sound must be kept in a low profile, away from the mainstream and with a unique identity.

Absolutely, at least for me. I am very different from other normal people who wake up every day to go to an office or accept system standards. So this phenomenon for me has its own identity, and even though throughout its developmental years many people have left to take on another identity, I know that we are thousands who still believe that this sound must be kept in a low profile, away from the mainstream and with a unique identity.

And I’m not talking about the aesthetic aspect, because personally, even though I really like the aesthetic that surrounds it, if anyone sees me on the street probably they will not think I listen to Death Metal. For me the image is not everything. It is the thinking, actions and congruence with yourself. The rest does not matter. Now, I will not dress like a Glam Rock fan of the eighties. No way!

How important do you think “non-commercial” attitudes are to the underground?

They are important to sustain its aesthetics, spirit and coherence with the environment. However, commercial attitudes are also valid. It is impossible to make a ‘zine and give it away for free, to spend thousands of dollars on a disc and then give it away. Money is in the middle of it whether we like it or not. Always. Moreover, we grew up on the grounds that money is everything. Unfortunately we are doomed to follow that path until humanity reaches its end. I prefer to make music or a magazine and sell it than belonging to a stupid company and take orders from an asshole boss.

Do you think the underground was a product of its time, when there was no Amazon and import CDs weren’t in regular stores, or does it still have relevance today?

To me, Underground is a concept born out of many factors, like our interest in something intangible like belonging to a music scene. We, are the ones who keep this alive. The bands, zines publishers, fans attending a concert, etc. All this makes the Underground continue thriving over time and avoid death to changes in humanity, like technology. Underground will always exist, but it is not going to go towards you, it is you who has to go to it.

What defines or identifies an “underground” band? Is there a specific sound, or is it an attitude, or a social position like being on an underground label, small pressing runs, etc.?

Arguably, in Thrash, Death, Speed, Black, Doom, etc, all trends derived from this devotion. Yes, there are patterns, pre-established rules and forms which we interpret as good or bad. Underground is devotion. And when it’s honest and pure, it is recognized. Who does not recognize it, then, they are on a different path.

How long did it take you to write the book? What is your process for writing?

From the first interviews, trips and design, I think it has been three long years. The first stage was the longest, perhaps collecting the information (posters, photos, etc.) and checking my personal collection amassed over the years of editing fanzines. Much of the material had been stored and forgotten.

Then it was about organizing the book concept and selecting the best of the material, trying not to be like any other work which has published about it. After several years, I think I arrived at the final concept. The experience of having done something similar, only dedicated to the scene of my country, was fundamental. That book, Retrospectiva al Metal Chileno 1983-1993, edited along with a 12″ vinyl disc (made by Iron Bonehead Prod, Germany) was very well-received worldwide.

Then it was about organizing the book concept and selecting the best of the material, trying not to be like any other work which has published about it. After several years, I think I arrived at the final concept. The experience of having done something similar, only dedicated to the scene of my country, was fundamental. That book, Retrospectiva al Metal Chileno 1983-1993, edited along with a 12″ vinyl disc (made by Iron Bonehead Prod, Germany) was very well-received worldwide.

Who’s going to print the book, and where/when will we be able to buy it, and for how much?

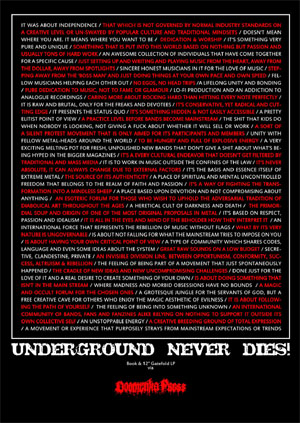

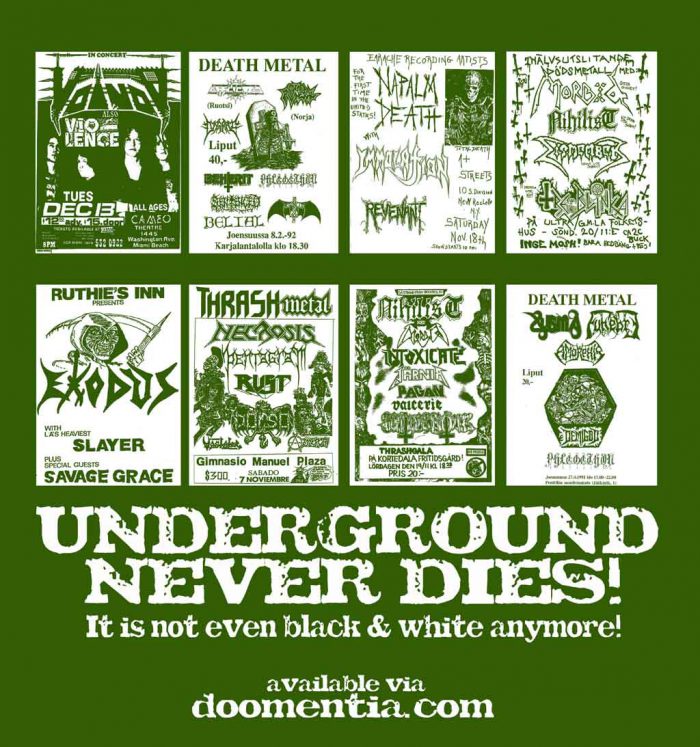

Doomentia Czech label will be responsible for publishing and distributing the book through its network of contacts and labels within the Metal realm. We all know who they are! If you’re reading this, it’s because you know! I have to confess that thanks to the Internet, now with a few clicks anyone can have the book. Hopefully the printed copies reach the right people. I have no idea what the price will be, but if you calculate a hardcover book with over 400 pages infested with posters and photos of the eighties, plus a 12″ gatefold with bands like Slaughter Lord, Incubus, Necrovore, Mutilated, Dr Shrinker, Fatal and more, then the price is more or less imaginable. I hope that the material is ready and available for December 2013.

You mention on your flyer that the underground was a way to fight transformation into a mindless sheep. This sounds straight out of “Invasion of the Body Snatchers” or “They Live.” Is it really that bad?

The promotional poster you speak of, contains quotes taken from the people interviewed in the book. That phrase you mention is something you will have to interpret when you read the book and the complete response of the interview. That mystery I leave it for when you have the book in your hands. Each individual has his own version of what happened in these corrosive years, when Metal was a threat to the system. In my case, I lived through Metal in chaotic times for my country with a military dictatorship. I think that counts and left a huge mark in our youth.

Where does the underground live today?

Worldwide. It has never ceased to exist. We are the ones who should feel a natural devotion to go after it. Those who don’t feel that, simply do not belong in this cult. This will cease to exist only when there are no more humans on earth.

Can you give us a small biography of yourself and your past writing experiences?

Since 1988, I have been editing fanzines, corresponding with bands, tape traders, attending concerts and festivals worldwide. I saw the birth of Death Metal since it started wearing diapers. With 25 years of experience in this art, I think I have enough to identify which smells more rotten than the other. This is all I have done in my life.

I have never been part of a company, nor have I been employed by one, except for a radio station in Santiago for three years, but at that time it was only two days a week on the radio, so I wouldn’t call it being employed by them. The program was called “Ground Beef”, and was devoted to Metal . We played stuff like Morbid Angel, Cannibal Corpse, Nihilist among many other killer bands. It was a fun experience hanging out with some international acts when they played in Chile.

Will you be covering the internet, for example pre-1995 websites like the Dark Legions Archive?

The book mainly talks about the beginnings of Metal, but at the end it has a brief chapter on these issues, the emergence of the Internet and databases such as these and many others, like Metal Archives.

Thank you for this interview. Our readers will enjoy it!

Thank you very much to you for this tremendous space and support to spread this work that has required three years of my life. I hope that when it’s published, the public can appreciate it.

3 CommentsTags: andres padilla, Black Metal, book, death metal, grinder magazine, underground metal, underground never dies

The good thing about the transition to two decades of operation is that a genre may benefit from advances in technology and funding to re-release its classics in restored or originally-intended form. Through this channel a burst of classics on vinyl has emerged over the past five years.

The good thing about the transition to two decades of operation is that a genre may benefit from advances in technology and funding to re-release its classics in restored or originally-intended form. Through this channel a burst of classics on vinyl has emerged over the past five years.