Writers review individual bands to strengthen a genre by promoting the better acts, but when writers turn to address the metal genre as a whole, the “state of the metal” reports that result are an assessment of the collective mentality of the community which produces and appreciates that form of music. Currently, this writer looks wryly at the metal community and proclaims, “It is afflicted with pity.”

To put us all on the same page, we’ll synchronize our definition of pity starting with this gem from the Merriam-Webster Dictionary: “PITY implies tender or sometimes slightly contemptuous sorrow for one in misery”1. In other words, feeling sorry for someone from a position of being more fortunate. As F.W. Nietzsche brilliantly revealed, this is a subtle and passive way of placing oneself higher than the person being pitied; “it must suck to be him” is a relative measurement which requires that the speaker know what doesn’t suck.

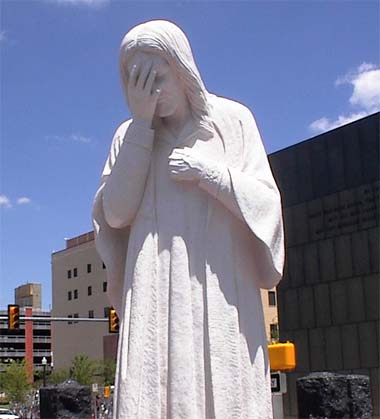

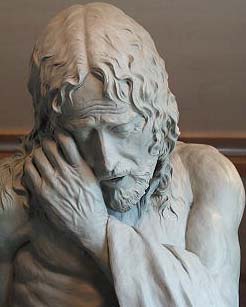

Pity also plays into the “good guy” sense of self when one takes action according to pity. A burned out, feces-encrusted, proto-Simian intelligence who shuffles out of the city sewer system to ask for handouts can be pitied and handed a trivia of pocket change, making the giver feel important as the groveling lice habitat demeans himself in the presence of his benefactor. Even someone who is basically impoverished can feel richer by giving someone less fortunate a nickel; some say this explains sympathy sex from ex-girlfriends. Pity is the basis of all Abrahamic religions, including the ubiquitous and demented Christianity.

Pity also plays into the “good guy” sense of self when one takes action according to pity. A burned out, feces-encrusted, proto-Simian intelligence who shuffles out of the city sewer system to ask for handouts can be pitied and handed a trivia of pocket change, making the giver feel important as the groveling lice habitat demeans himself in the presence of his benefactor. Even someone who is basically impoverished can feel richer by giving someone less fortunate a nickel; some say this explains sympathy sex from ex-girlfriends. Pity is the basis of all Abrahamic religions, including the ubiquitous and demented Christianity.

Since reality is not literally symbolic, except in certain Hollywood fairytales, pity in metal doesn’t pop up and scream its own name at the top of its lungs. However, it is clearly visible in the actions of metal as a community following the conclusion of the formative period of black metal in 1996 or so: increasingly, the goal in metal has been less to produce amazing music that a few understand, and the new goal has been to produce music that more people understand. An astute observer will note that dumbing something down for someone else is, similarly to the pity equation, a way of claiming to be smarter than that person; “here, I’ll translate it into shuffling, groveling, lice-infested prolespeak for you” is an equivalent statement of purpose. (And you wondered why the ANUS refuses to write reviews in the tongue of the common man.)

Originally, black metal was a byproduct of the genesis of death metal, something aesthetically inspired by Venom but really a derivative of melodic hardcore like Discharge, spawned in acts like Celtic Frost, Sodom, and Bathory in the early 1980s. It lay dormant until the next decade, when the Norwegians singlehandedly revived the genre by brushing aside much of the stridently-voiced social criticism (read: “complaining”) of speed and death metal and bringing out something with heroic ambitions, in which the greatest value wasn’t communicating to everyone but communicating to the part within everyone that wishes to rise above the mundane world and achieve great things; to have this spirit, you must believe that change can occur and is in the power of the individual. In this it was grand Wagnerian tragedy, the entire genre, as its practicioners knew they were hopelessly outnumbered and would be outvoted by the masses, who prefer tamer fare and resent anything that forces them off the couch.

Regardless of this adversity and sheer defeat, the Norwegian forces – we’re talking about Burzum, Emperor, Immortal, Darkthrone and Mayhem – mobilized themselves and went on the warpath to speak their piece no matter how unpopular it was. At first, although no one remembers this now, black metal was considered the retarded younger brother of death metal. Only a handful of people listened to it, and even then most of those didn’t understand it, or claimed they were doing it for the laughs. Only a few people caught on to its concept, and thus both its artistic method and ideological content. And before the old tired “music doesn’t have ideology” whining begins, we should realize that black metal was designed to sound like Gothic doom descending for a reason, and for one to believe that art should sound like that at this period in history, one must have a certain ideological bent – one that disagrees with the mainstream and foresees doom in its populist undertakings.

It was heroic, Romantic, passionate and yes, elitist; black metal was not music for the masses. Those who say at the current time that the values of the original black metal bands don’t matter, and who suggest we “progress” to other values (values that suspiciously resemble those of every other genre in its twilight years, namely values that make it more accessible to wide ranges of people because they approximate the liberal beliefs of a democratic social order), should ask themselves what over the past eight years of metal has had the impact of the original handful of bands, or attained that level of quality. The answer is: very little, if anything. The Norwegians remain absolute in their dominance of this artform, although nothing from Norway has approached that type of intensity since about 1997. We can see in the history of black metal’s descent into popularity the proof of the original concept as elitist and withdrawn from the masses.

It was heroic, Romantic, passionate and yes, elitist; black metal was not music for the masses. Those who say at the current time that the values of the original black metal bands don’t matter, and who suggest we “progress” to other values (values that suspiciously resemble those of every other genre in its twilight years, namely values that make it more accessible to wide ranges of people because they approximate the liberal beliefs of a democratic social order), should ask themselves what over the past eight years of metal has had the impact of the original handful of bands, or attained that level of quality. The answer is: very little, if anything. The Norwegians remain absolute in their dominance of this artform, although nothing from Norway has approached that type of intensity since about 1997. We can see in the history of black metal’s descent into popularity the proof of the original concept as elitist and withdrawn from the masses.

After all, populism – or dumbing something down so that everyone in the herd can appreciate it – is a form of pity and negativity. It doesn’t have a heroic “do what must be done and damn the crowd” outlook, but cares about its status in the eyes of others and in not offending them by producing music that’s too complicated for their addled capacity. This populism is pity for the idiots who must have music tailor-made to their retarded consciousnesses, as well as being pity for the musicians themselves: the art of expression and finding reasons to believe in one’s own existence have been supplanted by keeping other people happy through being bland. Interesting how bland well describes recent black metal in the eyes of anyone but a fanatic who, thankful for some social scene that will accept him, embraces the genre like a lost parent.

Way back in the 1980s, when speed metal was first disintegrating, people talked about “selling out,” or dumbing down your music so that more people would buy it. By the time of black metal, it’s no longer “selling out” that’s the problem, but “becoming populist,” or taking a genre of archly unique neoclassical metal and turning it into the same three-chord, constant-rhythm morass into which death metal, speed metal and hardcore music before them all degenerated. This occurs in two forms, of course, the purist (“tr00 black metal”) and the avantgarde, the former trying to ape the format of the original works and the latter trying to turn them into something combined of odd parts of other genres. Neither succeeds because the focus is no longer on the music, but on the crowd.

Of course, to adopt the attitudes, values, and musical methods of every other genre out there returns metal to the level of generic music; it is assimilated by rock music, which was formed only through a desire to appeal to as many people as possible, and loses its uniqueness except in terms of the poses its fans strike and the antics and novelties its bands bring to the stage. It has lost heroism, both in music and in action, and thus has become another voice clamoring loudly of its uniqueness when that uniqueness died long ago. To persist in making such sold out and generic music, one must be negativistic to the degree that one believes no stirring music is any longer possible, thus “you might as well just make something people like.” Not only is this pity for the audience, but – as the virus of pity is wont to spread – it is pity for the self. No belief in ability to change the world makes one an emulator and, conscious of this status, one becomes miserable.

Of course, to adopt the attitudes, values, and musical methods of every other genre out there returns metal to the level of generic music; it is assimilated by rock music, which was formed only through a desire to appeal to as many people as possible, and loses its uniqueness except in terms of the poses its fans strike and the antics and novelties its bands bring to the stage. It has lost heroism, both in music and in action, and thus has become another voice clamoring loudly of its uniqueness when that uniqueness died long ago. To persist in making such sold out and generic music, one must be negativistic to the degree that one believes no stirring music is any longer possible, thus “you might as well just make something people like.” Not only is this pity for the audience, but – as the virus of pity is wont to spread – it is pity for the self. No belief in ability to change the world makes one an emulator and, conscious of this status, one becomes miserable.

Interestingly, metal isn’t alone in this. Punk music went down this path in the late 1980s and became the totally soundalike, rubber-stamp similarity we hear today. Today’s black metal bands espouse “being the most extreme ever” and therefore like to sing about killing everybody on earth, destroying everything, killing themselves and other forms of self-pitying trash. Lacking self-confidence, these shadows of past glory have all of the “extremity” of a six-year-old’s tantrum, but none of the honesty: they’re simply out of ideas, but since they can’t socialize otherwise, are afraid to admit it and move on to something else. Like the doom metal bands who sing about the meaninglessness of life, or the punk bands who complain for forty minutes about society and then finally spit out the truth in a “love song” about being lonely and virtually stalking some unsuspecting female, these people have run to the end of the line and have nothing to offer to us but their pity and, of course, a chance to pity them – after all, they need us the crowd in order to have a meaning to exist.