Article by David Rosales

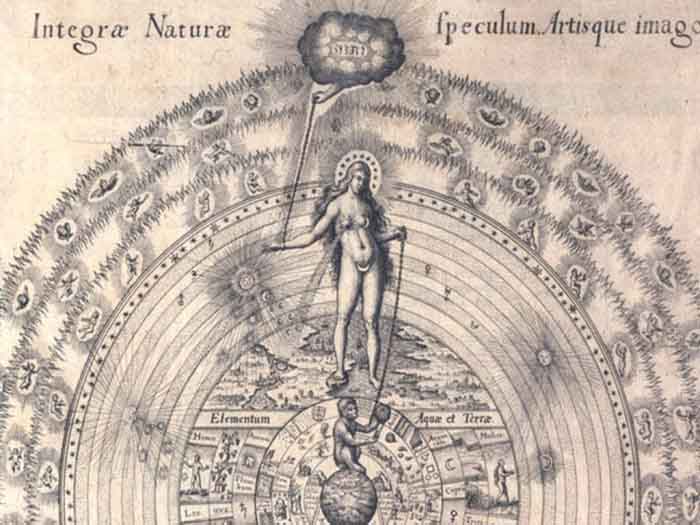

In ancient times, a transcendental and reverential cosmological vision made of the hardships of reality a way to elevate intellectual life to the status of the divine. The power to speculate, explore and decode reality around us was considered a gift.The time given to pursue such enterprises was considered invaluable.

What we now call history is the constant decaying of civilizations, an ebbing of true understanding, followed by a wave of revolutions, one after the other in relatively rapid succession as a drowning man desperately clutching for air. Scrapping whatever he could, man acquired dominion over the material while all sense of meaning was gradually lost.

“…for the powerful children of natural emotion will be replaced by the miserable creatures of financial expediency.”

The following is a list of four artworks of the greatest refinement, be it formal or otherwise, achieved through experience or birthed by the innerworkings of an innate calling. The first three are metal and of a minimalist stripe. The third is a Baroque religious vocal work. These are the echoes of what once was.

However, if there ever was an art for the elite, this is it. It will challenge each of the shortcomings of the fickle man. The first will call into question the superficial appreciation of aesthetics and will render the disavowal of prejudices compulsory. The second will require self-internment and the ability to perceive higher truths. The third will furthermore force those with a mind for the complex and an aversion to clear, straight lines to look beyond these and settle down in an openness to the expression. Finally, the last and most ancient will bring to bear the capacity of imaginatively layered music to quickly wear down the animal mind. This will be the bane of the simple-minded.

Disdained by most metalheads and followed with unthinking loyalty by kvlt fanatics, Ildjarn has achieved an infamous reputation in one way or another. Either of these camps considers the project to be non-music, with polarized opinions divided between “far from filling the requirements of music” and “simply beyond music”. The former point of view assumes a position of authority on technique whence it presumes to judge what music is. The latter is the inexcusable blindness of spineless and undiscerning individuals who place image before content.

While one could easily disarm the first argument on philosophical grounds, an unbiased judgement of the performance itself leaves any knowledgeable instrumentalist with no option but to accept that this is certainly not the weakness of the music. If issue were taken directly with the arrangement — the composition — of the music, there could be a worthwhile side to these attacks. More often than not, though, these critics arise from the new funderground camp, who have a notorious obsession with sheer standard behemoth-sounding production values, and so the argument usually runs along the lines of Ildjarn’s music being buried too deep in noise to have any value to speak of.

However, Ildjarn at its peak is far more than the jumbled improvisations the early recordings let through. The extreme punk channeling raw energy that this music consists of took some time to be harnessed. Det Frysende Nordariket (“The Frozen Northern-Kingdom”) shows us a refinement and redirecting of these ideas. While the self-titled was barely more than a collection of scattered ideas, intuitive impulses and visceral cadences, it is in this release that Ildjarn develops these ideas into mature extensions which make efficient use of the strengths of the original riffs, thereby burying the relevance of their shortcomings.

Coming to an aural absorption or a gnosis, so to speak, of Ildjarn’s rougher side necessitates not only the listener’s amiability towards ultra-minimalist and long-winded ambient music, but also a positive familiarity with low-fi punk and metal production and its use of what are normally considered sound artifacts as tones and colors on the palette of the artist. Once this is understood and the raw texture is successfully digested, one can start to appreciate the unique ideas presented in each track. The genius of Ildjarn lies in the masterful ultra-minimalist manipulation of the original ideas that can be likened to a stretching and contracting, which is occasionally accompanied by a seamless expansion that is so shy it is barely noticeable if the listener is not attentive.

1994 marks the turning point in metal history when innovation stops and a gradual degeneration starts to take place. This year is also the highest point in black metal, seeing the release of what we can consider the quintessential genre masterpieces. First among them is Burzum’s Hvis Lyset Tar Oss.

The meteoric ascent of Vikernes’ previous works from varied yet focused ideas to the purest synthesis of elements in Hvis Lyset Tar Oss could only have one possible outcome. The groundbreaking impact this had on the genre can only be compared to that of albums like Onward to Golgotha or Legion on death metal. While some argue that Vikernes single-handedly “developed” or “defined” black metal, the truth is that he brought it to an end in this album. It is the kind of album that has the words “THIS IS IT” written all over it. There is nothing for us, mortals, beyond the incognizable infinite.

While there is much dark beauty in other works in the genre, works that may serve as veritable portals to hidden corridors of existence, when it comes to the art of composition, there is no other that brings this black romanticism to a more perfect incarnation. Hvis Lyset Tar Oss addresses all facets of black metal and gives them an equally important place in a masterfully balanced music.

The often-used descriptor “ambient black metal” falls criminally short of what this album has to offer. That this “atmospheric” feeling is the only thing blind men can perceive is empiric evidence of its extant layers penetrable to their last consequence only by esoteric means. The least trained will only hear repetition (variation details are lost on them), while those into ambient music will sense the fog around them. He who decries structures and can, to some extent, understand their relations, will be able to delineate muscle fibers and bones — an objective confirmation of content. Further and higher lie realms to be walked but never shared.

Navigating the waters of this ocean, we see indomitable and gargantuan waves slowly rise before us, we experience the placid breeze under a dark-grey sky streaked by clouds mutilated by the rays of a moribund sun, and we face the wrathful tempest. Battered and sucked into a timeless maelstrom, all that remains at the very end is the essence, the ultimate undifferentiated mother of creation.

On The Rack

Asphyx’s debut garners “historical” respect, but is often deemed to be the preparative stage before more refined ones. This argument appears to be supported on two pillars. The first is that a later Asphyx was more technically outspoken, and the second, that the band managed to narrow down their style into a more focused expression. Both of these are true, yet they did not result in higher artistic merit as later works became increasingly sterile. The fact that people get “a feeling” from them is besides the point. Yet, when it comes to art and especially to music, some might confuse these visceral reactions with effective communication through the intuitive.

The Rack presents a style that is both minimalist in its building blocks but displays a progressive tendency in the overall arrangement of parts. Here, Asphyx goes beyond style fetishization and instead uses characteristic phrases and riffs as symbols standing for moods and points in a storyline. This vision places it alongside classic albums that work at a higher level than the merely technical or the grossly emotional. However, it is important to keep in mind that all this intellectual dissection is only a way to uncover this work’s secrets and must not be confused with the end.

The color palette with which Asphyx plays has a narrow enough range that its extreme opposites are not as contrasting that they incur in an incoherent string of topic changes, yet the individual strokes that riffs represent are distinctive enough that they form clear statements and unambiguously show the way. The triumph of The Rack lies, furthermore, in that it not only signals these inclinations but actually follows them to their last consequence without derailing.

These progressions may seem too clear-cut, leading to them being perceived as ‘blocky’. But when inspected closely, they are shown to be not so much as separate stones in alignment, but as rock-hewn steps in a massive staircase of which each stage is birthed from the underskin of the last. Other ‘brutal’ albums constitute a string of emotions, but here we find an ancient megalithic maze that dwarves petty human creations.

Switching between thematic solos and motific riffs, grindlike attack and doomlike arrest, this first Asphyx takes us through savage plains and forbidden peaks in a barbarian’s world. Now we hear the rage of souls crushed, the karmic cruelty thence resulting, now the ecstatic state following the release of unrestrained fury as we claw our way through this arid wasteland of unmercy.

On Historia der Auferstehung Jesu Christi (recording by Roger Norrington and the Schütz Choir)

A baroque religious work might at first seem like an odd addition to a metal compendium, especially one featuring such corrosive albums. A sympathetic relation may nonetheless be found in deeper metaphysical recesses. This hidden concept being the most relevant connection that merits mention does not stop us from discussing other outer traits that surface from that common source, even though their materialized natures lie at antagonizing angles.

The homogeneous, cloudy exterior of Schütz’s offering to the highest being is a continuous exaltation in which each moment is as much a unique apparition as it is an illusory shadow in a sequence of conditioned stages. A flow through condensation, solidification and dispersion let the listener on to the infinite possibilities arising from the two, who are themselves from the one.

Dense, saturated and appreciable only as a mass, Historia der Auferstehung Jesu Christi will only reflect a clear image if the listener is standing in the right place (at the right time?). This same is true of the Ildjarn, the Burzum and the Asphyx as well. They represent mental spaces within which they are as palpable and engulfing as daylight itself. But places must be traveled to, gates must be unlocked and the decision to step through them is a voluntary one.

Seeds being planted,

guarded by the old ones below.

Against the sky they lay roots,

Once to bloom with signs.

Tags: asphyx, burzum, elitism, ildjarn, metal history, Philosophy

Digesting this article is going to take some time.

I don’t even know what a lot of these key words mean. I’ve never read them before.

I also haven’t heard any of the music in question either, although I have heard, and very much like, Burzum’s “Det som en gang var” and “Burzum”.

Smashing article which I think could be expanded more to include even earlier music; e.g., antiphonal byzantine rite compositions & some work by the latin schoolmen (perotin/leonine), too. Excellence is able to wear any mask! Strong article — thanks for the post.

What are your thoughts on the seqencing of Hvis Lyset Tar Oss- how do you feel about the last track? Do you always listen to the album straight through?

Almost always! And Tomhet is probably the song I listen to the most on its own. Possibly the only one I listen to on its own. It is the most pure expression of what Burzum’s music is! I know it is not easy to just ‘see’ at first…

I think the sequencing (I assume you mean the order?) is perfect!

A description I read, I think by Prozak, explains it nicely.

It’s an increasingly rising slope that culminates around the half of the third track, then it calms a little.

The last track, I think, serves to bring everything back. Without this last one, it wouldn’t feel like a full circle, IMO.

Do you do early Klaus Schulze? Tangerine Dream? Dead can Dance?

Before I read that Varg intended for people to listen to his music whilst falling asleep, I actually did so. Finally succumbing to your unconscious self whilst Tomhet is droning is a surreal, ritualistic experience. I listened to the album a few times and those experiences haven’t been rivalled since, even with subsequent repeat playings. That whole album is like a cleansing. I was a lost teenager traipsing through midnight fog on the marshland and a new-found landscape of existentialism. Hvis Lyset Tar Oss dissolved me in its grasp and demanded deeper perception.

I definitely enjoy Tomhet and where it takes me, and obviously the record is an incredible work, but I always found it curious to have three straight black metal tracks and one longer ambient keyboard piece to close the record. It concludes it very well, but as a full piece I would have been more apt to appreciate its role as something to bookend the other songs had there been a similar piece at the start of the record. But perhaps the lack of album symmetry is the statement Varg had intended to make.

I enjoy Dead Can Dance but am unfamiliar with the others. The kneejerk reaction to Tangerine Dream was to avoid due to their name, which I know was a mistake before with the cases of similar hippie monikered shit like the Flower Travellin” Band so if they are recommended I’ll check them out.

Try their stuff before 1975.

And with regards to what Varg intended or not, it is not really important if you are not able to see it, I think. How much can you feel it means something and it is complete.

I do not know what Varg intended, but perhaps it is as you say, since it is the same story when we see his different works. Look at the album Det Som Engang Var before this one and the one after, Filosofem, they also follow this build-up, then intensity as the main body, then rest

I’d put in a recommendation for 1976’s Stratosfear, too. It’s interesting to hear Tangerine Dream exploring their usual niche in a more conventionally instrumented and structured fashion. Probably the closest they get to neoclassical of what I’ve listened to, although I ought to expand my knowledge of TD’s work.

I’ve never understood why certain members of this community say metal died in 1993. Death metal did, perhaps, but 1994 was THE year for black metal.

Burzum – Hvis Lyset Tar Oss

Darkthrone – Transilvanian Hunger

Emperor – In the Nightside Eclipse

Gorgoroth – Pentagram

Mayhem – De Mysteriis Dom Sathanas

Enslaved – Vikingligr Veldi

These were all released in ’94.

Even death metal wasn’t quite dead, with A+ albums like For Victory and To the Depths… alongside other minor classics.

Actually, That’s what it says here, 1994 was THE year for Black Metal, hahaha

And death is not sudden, but gradual, all the good albums after these dates are fainting echos

See Obscura in 1999, all “innovation” is only on the exterior, there is nothing really developed. Cool album, though.

1998

…Although one could argue that, for those albums to be released in ’94, much (most?) of the music on those albums was probably written by the bands in ’93 or earlier.

That’s just Bitterman bull.

Second wave black metal fell off harder than American death metal with regards to quality after 94-95ish but both not nearly as much as say Swedish death metal. Death metal still had the New Yorkers Immolation/Suffocation/Incantation, An Ending in Fire, None So Vile, etc. I don’t think there’s anything worth repeated listening from the original Norwegian black metal scene that was released after Kvist except for Blizzard Beasts (which is Morbid Angel death metal). I’m not counting melodeath/black of course.