Article by Bill Hopkins

“We might even say that to be fully modern is to be anti-modern: from Marx’s and Dostoevsky’s time to our own, it has been impossible to grasp and embrace the modern world’s potentialities without loathing and fighting against some of its most palpable realities.”

—Some overweight sociology professor

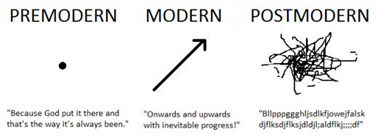

Metal, like any manifestation of culture, doesn’t emerge from a social vacuum. So much should be uncontroversial. This raises a question in need of reply: What set of ideas and social forces explain the existence of metal? One hypothesis is to view metal as a manifestation of European romanticism [1], the period of European culture from roughly 1789 to 1850. This article suggests a different hypothesis: namely, that metal must be placed against the backdrop of post-modernity in order to be properly understood. In order to make this case, it is vital to understand ‘post-modernity’. Many confuse post-modernity (1960s-) with modernism (1890s-1930s), especially when it comes to art. Thus, a secondary goal of this article is to illuminate post-modernity. I will argue that one key imputes giving rise to metal was post-modernity’s re-engagement with past forms [2].

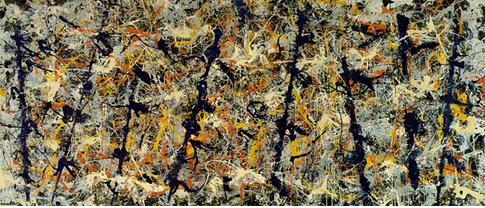

One naïve view of post-modernity, especially in its artistic manifestations, views it as an elitist movement intent on offending traditional and bourgeoise sensibilities by embracing the ‘shock of the new’ and the absurd: think of the sort of art piece your intellectually disabled 3 year-old could do if given a paintbrush and a blank canvass stretched out on the floor. However, this is to mistake post-modernity with modernism[3]. Modernism preceded post-modernity by decades. It began in the late 19th century and had all but dissipated in time for the lead up to WW2. Not only this, modernism was primarily an artistic movement whereas post-modernity refers to sweeping social and economic changes in addition to artistic ones.

‘Blue Poles’ by Jackson Pollock

As we will see, post-modernity is characterised by a re-assessment of modernism’s ‘shock of the new’. In order to explore post-modernity and its connections with metal more fully, however, we need to take a few steps backwards before going forwards. We need first to understand the broader concept of ‘modernity’ (1789-). What is modernity, such that ‘post’-modernity is contrasted with it?

Modernity

The onset of modernity can be identified with the French revolution of 1789. However, the social, economic and cultural factors that led to characteristically ‘modern’ revolutions like the French (and also the American) were in place long before the storming of the bastille. Perhaps the most important factor in the rise of modernity was a revolution of the non-political variety: the scientific revolution of the 17th century. Among other things, this revolution made possible the industrial revolution of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. As an economic phenomenon, the industrial revolution gave rise to sweeping social changes: most significantly the emergence of the new industrial-capitalist middle-class (the ‘bourgeoisie’). The stake of this new industrial middle class would continue to rise, as that of the aristocracy fell, until roughly the end of the industrial era. The onset of the ‘post-industrial’ era after world war 2 saw the rise of a new ‘yuppified’ middle class dealing in information and cultural services as opposed to material goods. (Indeed, post-modernity – one prominent sociological theory of ‘post-industrial’ society – is often seen to begin where industrial modernity ends).

Another key factor in the rise of modernity – again with causal antecedents in the scientific revolution – was the European enlightenment. Beginning in the mid-18th century, thinkers such as Voltaire, Diderot, Rousseau, Hume, Adam Smith and Kant advocated the replacement of tradition, the church, and monarchy, with reason. The result was the refinement of a powerful reductionist-mechanistic method of scientific investigation, a privileging of the universal over the parochial and the local, and a penchant for individualism. The individual human being, free from the restraint of old customs and sitting alone contemplating the world using his faculty of reason, became a symbol of emancipation and progress – the latter being a key concept of modernity, and one which arguably dates back no further than the enlightenment.

Democracy, framed on the ideal of the ancient Greek polis and the Roman republic, became the favoured theory of government. If not democracy then ‘enlightened absolutism’, at the very least. Although not widely endorsed, atheism became a publicly acceptable topic of conversation among the intelligentsia. In the face of the absurdities of the bible, many thinkers settled instead for deism. In the cultural realm, classicism emerged from the baroque and the latter’s late pre-classical manifestation, rococo. Architecture, music and painting all strived for balance, wit, and uncluttered form. Clear skies, optimism, and objectivity were all in high order. Haydn’s 63nd string quartet – “The Lark”: Op. 64, No. 5 – perhaps perfectly embodies in musical form the ideals of the enlightenment and, as such, one current of modernity that remains with us in the form of classical (as opposed to ‘progressive’) liberalism.

‘An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump’ by Joseph Wright

The French and American revolutions represented the culmination – and some say the end – of the European enlightenment. The various factors that led to these political revolutions may be identified with the rise of the modern age: of modernity. Most important, the rise of modernity involves the emergence of a new progressive outlook related to an emancipatory linear view of history. With this, the scientific revolution; the industrial revolution; the new capitalist economy that replaced the landed aristocracy with the mill and factory owner; and finally the enlightenment, heralded a break with the past that cut across the entire society: economy and culture alike. Soon after its fruition, however, the enlightenment shared the cultural and social stage with a broodier and more introspective movement: romanticism. The enlightenment’s almost totalitarian stress on reason and objectivity lead to a reaction of the emotions and of subjectivity. This reaction was to reach fever pitch with the onset of modernism in the late 1800s.

Modernity and its Contradictions: Romanticism and Modernism

Romanticism began with the slaughter of the French revolution and lasted until around 1850. Where the enlightenment stressed reason, the romantic movement stressed emotion. Where the enlightenment stressed objectivity, romanticism responded with the primacy of subjective experience and the imagination. Further, enlightenment universalism was contrasted with romantic parochialism and nationalism. In the cultural realm, the ideals of enlightenment art – balance, wit, and elegance – gave way to stormy skies and the emotional ‘profundity’ of the individual artist. A fascination with violence and the exotic became features of romantic painting. Idealism (ontological sense) flourished in philosophy. Where the enlightenment represented a decisive break with the past, orientated towards the future, romanticism sometimes directed a searchlight back into medieval times and gothic aesthetics, seeking resources to critique an overly exuberant climate of rationalism and universalism.

‘The Raft of the Medusa’ by Theodore Gericault

Although romanticism was anti-enlightenment to some significant degree, it was not anti-modernity. This is a vital contention of the current article. Instead, romanticism is more accurately characterised as a novel current within the dialectic of modernity. Why? Firstly, because the whole history of modernity from the late 18th to the late 20th century shows the modern outlook to be beset by the kind of contradictions first raised by romanticism. Secondly, many of the romantic figureheads like Wordsworth and Shelley were enthusiastic supporters of the French revolution and looked forward to a political future of freedom, justice and equality – as did Beethoven.

‘Liberty Leading the People’ by Eugene Delacroix

Romantics, no less than others, saw the (then) present age as a time of new beginnings and potentialities. In the same way as the enlightenment, time was viewed as linear. ‘Progress’ was both conceptually coherent and normatively compelling. As such, romanticism arguably went along with the ideas and sentiments of modernity. In romanticism’s counter-propositional (in relation to the enlightenment) stress on subjectivity and the imagination, we can see being advanced an allegedly more holistic and complete understanding of the individual. Romanticism was concerned with those goods necessary for the fulfillment of human nature ignored by the enlightenment’s over-emphases on reason, objectivity and the universal.

Thus, history shows us that modernity’s elevation of human beings as self-determining and autonomous did not begin and end with Kant. The tendency to view time as linear and to scrutinise the present from the romantic position of historical awareness; to subject it to rigorous and critical analysis; and to uncover those goods (whether old or new) needed to repair the faults identified – delivering humanity into a new world of freedom and self-fulfilment – is about as modern as you can get. In this light, romanticism turns out to be thoroughly modern. It also gave birth to modernism (as opposed to ‘modernity’).

Modernism was a cultural movement, primarily in the arts, that blossomed between the 1890s and the 1930s. It can be most suitably contrasted with romanticism, not in its opposition to the (then) economic and social context of modernity and industrial capitalism, but rather in the intensity of its critique. Flaubert, Baudelaire, Rimbaud and Verlaine and the symbolists were arguably the first to express an increased air of pessimism which sometimes reached outright disgust. Kierkegaard, Dostoevsky, and importantly Nietzsche, joined in the chorus of despair. Modernism would flower in the first decades of the 20th century in artistic movements like Dadaism, Surrealism, Futurism, Expressionism, and Vorticism.

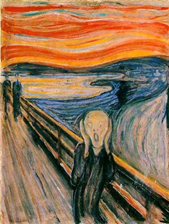

‘The Scream’ by Edvard Munch

Both the visual arts and the literature of modernism called into question traditionally modern (i.e. in the sense of ‘modernity’) epistemologies. Where romanticism, and even impressionism (an early precursor to modernism), preferred to highlight the subjective aspects of reality, they did not reject an objective reality with which the subject was in contact with, however indirectly. Many modernist artists, on the other hand, broke almost completely with realism. They also attacked the idea of a unified subject. In drama, playwrights rejected the idea of characters as whole and finished, instead stressing contradictory elements of personality and individual psychology. In Western art music, atonality, harmonic dissonance and rhythmic irregularity inhered in works starkly at odds with both the classical era of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven and the romantic era of Chopin, Schumann, and Brahms.

Perhaps the most shocking product of the era of modernism came from the newly emerging field of psychology. Freud’s dethronement of reason and fixation on the forces of the irrational and the unconscious presented a view of human nature that would have been horrific to the enlightenment mind. It also opened the way for the investigation of the occult, and to large degree the re-legitimation of mythology and religion. Moreover, and echoing Nietzsche, “Freud… put a gigantic question mark against the modern idea of progress. Civilisation… was, he suggested, achieved at the cost of enormous psychic suffering and enfeeblement” (Kumar 2005, p. 119).

As with romanticism, however, it is not entirely accurate to take modernism to be simply ‘anti-modern’. Anti-enlightenment and anti-bourgeoise, to a large extent, yes. But arguably not against modernity. Again, why not? Firstly, certain and indeed quite central tendencies within modernism enthusiastically embraced the ‘shock of the new’. In the artistic movements of futurism and vorticism, for example, the new systems of transportation like the train and automobile were revered. Life was depicted (and celebrated) from the staggered-perspective(s) of speed and constant movement without rest. In music, parts of Schoenberg’s musical expressionism were celebrated by cultural critic and Frankfurt School figurehead Adorno as exemplifying how modernist art could function as a critique of existing conditions and furthermore as a Utopian alternative to them. In Schoenberg’s ‘free atonal’ (pre-twelve-tone) period, the musical event was “self-ordering” and “autonomous”, as opposed to being subject to an external law imposed by the composer.

‘Cyclist’ by Natalia Goncharova

Even Nietzsche, despite what some take to be his cyclical view of history, is not accurately represented as a pessimist. After all, he did advocate a future goal for those select few who could, he thought, redeem the current mass of humanity in the bourgeoise-democratic era. These ‘overmen’ would, he hoped, make a complete break with the values of the bourgeoise, Christians, and with those strains of western philosophy that, in Nietzsche’s view, fled from the totality of life to embrace ‘otherworldliness’. Further, modernist architecture boldly proclaimed the new beauty of simplicity, of function and utility, and of efficiency. Schools of architecture following these principles operated with the leftist goal of raising the living standards of much of the population, and emerged from the German-speaking nations in the 1920s and 30s. They sought to remodel many German cities only to be supressed by the rise of Nazis leading up to WW2.

Bauhaus building in Dessau

These are only some of the ways in which modernism, as a cultural movement within modernity, is arguably far from anti-modern in spirit. As with romanticism, the desire to break with certain elements of the then contemporary social context stemmed from the desire to attain a more fulfilling future state of modernity for the individual. This is key to understanding modernism and its place within the age of modernity (1789-) more generally.

‘Post’-Modernity

Modernism refers almost exclusively to a cultural movement instigated by artists and writers. Post-modernity, on the other hand, casts its net much wider to encompass also the social and economic features of an era. Indeed, one feature of the post-modern account of society is the interpenetration and collapse of the cultural, the social, and the economic into one amorphous and confusing mass. Proponents of post-modernity frame the era as beginning sometime in the late 1960s with the eclipse of industrial society and its replacement with a new, post-industrial, society[4]. But why ‘post’-modernity?

Various post-modern theorists declared that contemporary society had superseded modernity for the very first time since the enlightenment. Integral to the view is the assumption that the various counter-movements to the enlightenment since the late 18th century, such as romanticism and modernism, emerged from a social context that was still very much modern: i.e., future-orientated, ‘progressive’ (broad sense) for the individual politically, and embracive of change.

A prime motivation for declaring the modern age to be finally over was the feeling that, as the second half of the 20th century progressed, the social and economic realities of contemporary life constituted something of an entirely new paradigm. Industrial capitalism was for the very first time being superseded by a new economic system in which distinctions between culture, society, and the economy no longer existed. Such distinctions previously allowed social theories like Marxism to differentiate between the economic ‘base’ and cultural/social ‘superstructure’ of society in order to stress, according to its materialistic orientation, the primacy of the former over the latter. But for the first time, according to the champions of post-modernity theory, the cultural and the social were being infused into the economic. Whereas the ‘stuff’ of the economy in the industrial-capitalist age of 1750-1960 was material, beginning in the late 1960s and early 1970s the economies of the West increasingly dealt purely in information, symbols, and other representations. This meant that the once useful distinction between economic base and cultural superstructure was being erased. Culture (the realm of representations) was no longer the tail wagged by the dog of the economy. Instead, culture was becoming the business of economics. Equivalently, economics was becoming the basis of culture.

Hundertwasser House in Vienna

Purely academic arguments aside, what is of greater interest for us are those features of the stage in social history some have felt deserving of the revolutionary title ‘post-modern’, whether or not these features do indeed suggest a decisive break with the age of modernity. By making these explicit, against the backdrop of the abovementioned points about modernity, we can then see where metal fits in. As mentioned, we have the rise of the information economy in place of an economy based predominantly on materials. We have the novel goal of melding ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture, realised in newly designed shopping malls mixing the boutique with fast food. We have a weakening of institutions and practices based around the industrial-era sphere of the nation state. Mass political parties based on class gave way to an politics based around concepts of gender, ethnicity, locality, and sexuality. Class politics gave way to identity politics. Moreover, national cultures were to a significant degree replaced with ethnic, religious and cultures based on age, gender or sexuality. With this, a ‘politics of difference’ largely replaced a politics of (national) unity.

Further, society experienced the reversal or qualification of the spatial orientation of industrial modernity. The concentration of populations in large cities was countered by a movement of decentralisation and dispersal. Small-scale schemes became increasingly trendy, linking people to neighbourhoods and aiming to cultivate the ethos of particular places and particular local cultures. A move from the universal to the particular took place in town planning. Society underwent the ‘re-discovery’ of territorial (as opposed to national) identities, local (as opposed to national) traditions, and local (as opposed to national) histories.

Another vital trend in post-modernity (1960s-) is the dissolution of grand (and linear) historical narratives. The key ‘grand narrative’ that was increasingly eroded in leftist circles during the progression from existentialism to structuralism to post-structuralism was Marxism. Marxism, in its classical form, advanced a science of history that purported to incorporate empirical insights and predict future social developments: it was a projectable materialistic theory of the social stretching across history and into the future. Another grand narrative that became unfashionable is arguably the very one underpinning modernity itself: the idea of progress based on a universal human nature. “Intellectual terrorists” like Foucault, Derrida, Deleuze and their ilk, echoing somewhat modernist assaults on the unified subject (but for entirely different reasons: the assaults of the modernists were inspired largely by the empirical pretensions of Freudian psychoanalysis, the kind of ‘objective’ enterprise post-modernists like Foucault questioned), sought to deconstruct the subject out of existence and dissolve him into the nihilistic wanderings of linguistic discourse: a kind of social-institutional-semiotic process of ‘drift’.

Despite attempting to withdraw the very conceptual basis of ‘progress’, post-modernists nevertheless (and somewhat confusingly) sought to lend their support to the modern left’s projects of identity politics. But what basis was there left for normative judgement after the complete deconstruction of the human subject? Post-modernists waxed lyrical about the “replacement [of grand historical narratives] with the ‘little narratives’ of more localised groups” and “self-legitimising stories which determine their own criteria of competence and define what has the right to be said and done” (Kumar 2005, p. 157). This “atomisation of the social into flexible networks of language games” did not seem progressive enough to some on the left, such as Chomsky, who rejected the terms of post-modernity as nihilistic.

Finally, post-modernity took its critique of what it saw as the modern progressive myth to its limits by highlighting the environmental destruction caused by nearly two centuries of industrial capitalism. The classical liberal/enlightenment dream of individual liberation through participation in the free market of material production and consumption was for the first time widely acknowledged to be more like a route to mass death and destruction than (at least long-term) human liberation.

Post-Modernity and Metal

Let’s finally cut to the chase and address metal. First, we need not attempt to uproot metal, traverse time, and place it within European romanticism (1789-1850) in order to position it within social context that borrows from the past. One of the defining features of the post-modern era is its rejection of modernism’s obsession with the shock of the new, and what resulted was a search for identity and belonging in the historically ‘authentic’ (see also the ‘historically informed performance’ movement in recent classical music). While isolated currents within metal – for instance black metal – might employ past imagery in a less ‘ironic’ spirit than would make your average pomo professor comfortable, even within black metal the spirit of irony sometimes pervades. Immortal and Darkthrone would be prime examples here. Your Burzums and Gravelands are plausibly somewhat of a hardcore ‘vanguard’ when it comes to a deadpan embrace of traditional representations.

Second, the darkness and foreboding atmosphere of metal is arguably cut from the same cloth as post-modernity’s pessimism towards all theories of linear liberation, particularly the classical liberal/enlightenment assumption of ‘she’ll be right’ progress. Not only does metal side with the natural environment against the onslaught of a short-sighted materialist economics, it allegorically mocks that bourgeoise placing-of-death-and-darkness-and-eternity-in-the-‘too hard: ignore and focus on having tea’-basket:

I remember an old man griping my wrist, he was dying “imagine”, he said, “looking into the eyes of a nova, the bursting flames, the roar of its energy faintly echoing down the corridors of time, whispering: all life ends”.

—At the Gates

Metal is categorically not romantic, in that it did not originate out of the social, economic, and culture of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Of course, it sometimes displays similarities with romantic themes: for instance the gothic, the macabre, and the mythological. However, this makes sense within the post-modern era. The borrowing of symbols and images need not be first-hand. The post-modern artist can adopt the aesthetics of a past movement (like romanticism) that has itself borrowed from the past. Similarly, metal is NOT modern in the sense of embracing a linear and progressive view of history which prophesises some future utopia (where this utopia can be composed entirely ‘of the new’ or also incorporate ‘the old’).

“Is metal, then, post-modern?” In the respects just mentioned, yes. But, as with anything, the facts are not either black or white. The very best metal strives for what the romantics called the ‘sublime’. A rather dark version of it, to be sure, but the sublime no less. Post-modern art is usually too ironic to strive for such a goal, or else it is rendered incapable of doing so by other institutional factors. The main respect in which metal stands in tension with post-modernity, at least to this author, is in its ‘essentialist’ tendencies. I have talked about this more fully in a different article [5].

Briefly, the concept of essentialism has different meanings in different disciplines, but in the present context it should be taken to mean that which is not socially constructed. Social constructionism, a key theoretical tenant of

post-modernity, is the idea that reality is not something objective that is waiting to be discovered, but is instead created from “interactions between and among social agents”. As such, there can be multiple ‘realities’ existing independently from one another and competing for legitimacy. Philosophy shifts from a focus on ontology to an obsession with language: the ‘linguistic turn’. Metal attempts to cut through such language games by hammering home certain objective realities on the back of a blast beat – particularly those deemed ‘too hard’ by bourgeoise sensibilities. Further, it seeks to artistically ‘redeem’ these realities in a sense not too dissimilar from what Nietzsche identified as the ultimate goal of tragic art in the age of the Greeks: to convey the experience of a resounding ‘yes’ to life in its multifarious totality.

References

Kumar, K. 2005. From Post-Industrial to Post-Modern society: New Theories of the Contemporary World.

Notes

[1] See the article Metal as Antimodernism: https://www.deathmetal.org/article/metal-as-anti-modernism/

[2] However, within post-modernity embracing the past is deemed ‘OK’ only if done in the spirit of irony. No one tradition can demand our allegiance, the story goes, due to the fact that we post-moderns are exposed to all human traditions across time and space.

[3] Modernism is not to be equated with ‘modernity’. Modernity encompasses the enlightenment, romanticism, modernism, and some even say so-called ‘post’-modernity. Modernism was primarily an artistic movement from the 1890s to the 1930s.

[4] Indeed, post-modernity is but one theory of post-industrial society, within sociology.

[5] See the article Is Death Metal Essentialist Music?: https://www.deathmetal.org/article/is-death-metal-essentialist-music/

Now that’s an interesting article raising good questions and exposing important ideas. This is what I expect from this site. I would be curious to see where people will rank Metal in 100 years from now.

Let us hope the good is remembered over the bad. Hence the importance of a site like this!

The present commenter’s words will be displayed once they have something worthwhile to say and they are able to articulate in a gentlemanly/ladylike manner.

I will not hurt or harm you. Just give me back the board, Lance. It was a good board – and I like it. You know how hard it is to find a board you like.

Fantastic article: informative, well articulated and argued. I am skeptical that any of the post-modernist leanings of the metal “movement” (if one can be so brazen to call it that) can be attributed to more than the social context in which it arose. It seems to me that the focus of metal on the very real tension, which you correctly highlighted, between the epistemological subjectivity of post-modernism and the unwillingness of society to confront dangerous and controversial ideas precludes it from existing as post-modernist art. Instead I would argue that extreme metal was conceived from a post-modernist pessimism and anti-modern rebellion against progress, ideas which appealed to young misfits, and was used to create ‘sublime’ art which stood in stark contrast to the disposable, facile society which they saw. I think that is the one big part missing from this article – the movement from a materialistic economy to a disposable, transient economy of fads and cheap trinkets in the post-modernist age. Great points nonetheless.

Yes I address this, but only very briefly at the start of the section of post-modernity: The cultural becoming the economic, and vice versa.

The essence of black and death metal is the fatalist and final dying breath of an imagined culture that its artists associate with. I am sure that is how it actually will turn out to be, if history remains to be recorded.

The themes of BM & DM are basically that common mythology is trampled and lost, weakness and disease is spreading, individuals are at mercy, death is inevitable and humanity is unimportant anyway. What intellectual space is left after this?

Aside from empty innovations in technique and the whimsy of fashion, there will be no more “movements”, for everything has already been deconstructed, there is no creative consensus and there is nothing left to build upon.

Lovely article. For what it’s worth I’ve always viewed Black Metal as a modern art in reaction to modern art. To this effect metal embodies aspects of what are arguably pre-modern arts in a conscious act of self-differentiation from what they ultimately are. But as to what constitutes the thrust of metal, there is the simple awareness that the world IS beyond and above any question as to what it is- a given that comes before anything we can say of that given (even the ontological statement that It Is). That brute facticity could be considered as a kind of archimedean given for metal, which is why to music-critic/Sonic Youth folks it seems ‘naive’ for fixating on heroism, ‘evil’, romantic archetypes. Metal is derided by the ‘ironics’ as too serious.

In a sense I think metal is a genre that recognizes ‘givens’ not by talking about them but by trying to embody them in the musical context, for the world IS and it IS in a way that has been ignored by a creature that has the luxury/confusion that post-modernism indicates.

I agree.

Teach me: why “archimedean”?

And please do go on.

And especially self-proclaimed “metalheads” are these ‘ironics’ who deride metal for being to serious. Those who would go beyond the “metalhead” point are seen as crazy or overly involved, or something else.

I might have committed a bit of a gaffe here but let me try to explain my usage.

I meant it in the analogical sense Descartes does; as an unshakable point from which he can derive the certainty he needed.

“Archimedes, that he might transport the entire globe from the place it occupied to another, demanded only a point that was firm and immovable; so, also, I shall be entitled to entertain the highest expectations, if I am fortunate enough to discover only one thing that is certain and indubitable.” (2nd Meditation)

There is a kind of finality and undeniability in it.

Or from wikipedia straightforwardly: “The expression comes from Archimedes, who supposedly claimed that he could lift the Earth off its foundation if he were given a place to stand, one solid point, and a long enough lever.”

I think metal is distinguished precisely because it has one in the sense I tried to speak of earlier. Without this ‘point’ there is nothing to affix the genre to that is relevant- you end with dissipation. This website has made a big deal of iterations of such a point. “Only Death is Real” is a fine iteration of it, but it could also manifest itself as other final/fatal formulas.

Note: This is not to say everybody needs to be some ‘philosophical insurgent’ to make music, generally at this point it makes the music self-referential. Metal itself irrespective of its practitioners is a kind of insurgency simply by claiming some things simply are without qualification. Or that there is some fatal yes/no binary in the world that we have sophisticated away.

Irony is one of the most disgusting and wretched features of modern culture. I’m pretty sure Brett Stevens wrote an article on this about ten years ago.

I wonder if I can find it…

http://www.anus.com/zine/articles/irony/

There’s a clear Nietzschean sentiment in there. Irony becomes a substitute for having (in chronological order)

1.) Having ideas

2.) Having a personality

3.) Having a soul.

This lands you in the bedlam of most postmodern philosophies, arts, etc.

It’s incredibly invasive because like bureaucracy it’s asexual and self-replicating.

Or straight from N’s mouth: “The fatalism of the weak-willed embellishes itself when it can pose as … good taste.” (the extract excludes a bit about sufferance for the sake of humanity at large, but the format he presents is conformable to our phenomenon as well.)