(Join DMU Legend Johan Pettersson for what may be the most expansive analysis of power metal ever presented in the first of a 3 part series. Listen to the accompanying suggested listening here)

Of all the subgenres and styles that fall within the metal spectrum (hence excluding unmitigated relapses into rock such as death’n’roll, stoner, nu- and indie metal), power metal most definitely counts as the one that has received the highest amount of scorn and ridicule from critics, fans and outsiders alike. Despite being located at the bottom of the pecking order, the power metal “movement” has stubbornly toiled on for over three decades packed to the brim with musical epiphanies and fads alike. Practically declared dead by the early 1990s following the rise of death and black metal, power metal experienced something of a renaissance around the millennium and has remained popular ever since.

While discrepancy between popularity and critical acclaim is hardly a rare phenomenon, the factors behind such divides can differ significantly. When it comes to power metal, there seems to be something inherently embarrassing about it. Not only is power metal often deemed artistically inferior when compared to adjacent subgenres, it is also perceived of as something that should not be taken seriously. For example, there are many stories where even the most seasoned of metalheads express a certain unease about someone overhearing them listening to a power metal record, even though they evidently show interest in the music in secrecy. Moreover, power metal has worked as an entry point for thousands of younger metal fans, who after delving deeper into the genre tend to denounce or conceal their earlier, supposedly misguided enthusiasm. Boasting a background in traditional heavy metal is perfectly legitimate, but for many power metal is definitely a no-no.

A further and perhaps more critical indication of power metal’s poor status within metal culture concerns the ultimate lack of literature dedicated to the subgenre in question. With a few notable exceptions – including an excellent article by a former DMU associate – very little has been written about the history, taxonomy, spirit or musical properties of power metal in a more systematic fashion. This three-part article has been written with the aim providing a rudimentary yet comprehensive introduction to the subject which could in turn open up for discussions about the potential and relevancy of power metal. If we are to believe the predictions presented in a recent publication courtesy of Spotify where power metal occupies the number one positions of “emerging genres” for 2017, such an endeavor should be in pressing demand.

Origins

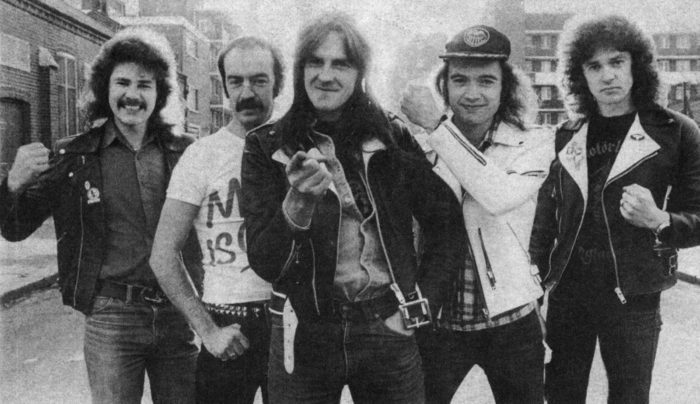

After Black Sabbath lied down the fundamentals for the creation of metal as a musical genre, it would take almost a decade before the first genuine metal movement sprung into existence in the form of the New Wave of British Heavy Metal. The NWOBHM, inspired by proto-metal, progressive rock and contemporary punk symbolized – at least in its ideal state – a decisive reaction against the corruption of metal music at the hands of stadium-oriented performers that had turned heavy metal back towards the rock’n’roll hedonism, blues-derived conventions and complacent inertia it once had sought to escape. Seminal NWOBHM acts such as Angel Witch, Iron Maiden and Satan both retained and discarded core elements previously pioneered and integrated by Black Sabbath, arriving at an updated, more codified form of heavy metal that would work as a springboard for further developmental within the genre.

When NWOBHM began to fade out by the early 1980s — very few bands continued producing albums, at least good ones, with the possible exception of Iron Maiden — it was clear that metal as a cultural force had not had it’s final say. British metal had an enormous impact on younger musicians around the globe, with hordes of underground-based bands charging ahead to declaim the insurgent voices of speed-, death- and black metal. Just as NWOBHM had modified and expanded upon what came before, Mercyful Fate, Metallica, Slayer, etc. began altering the established codex of metal music to fit their visions while at least initially retaining a connection to previous eras. In other cases, such as Hellhammer, this would include breaking significantly with the NWOBHM as well as resurrecting Sabbathian proto-metal techniques that had laid well-nigh dormant for well over a decade. Soon enough, metal had metamorphosed into forms that seemed to grow increasingly distant from the once so exciting sounds of early 1980s Britain. But just as this new breed of bands were busy with obliterating the rules of the past, another form of metal music – subsequently identified as power metal – took form which can be more accurately described as a continuation or extension rather than a break with traditional heavy metal. Deeply rooted in musical syntax and thematic established by the NWOBHM, power metal bands developed an identity of their own through the influx of both older and contemporary influences as well as by embracing a “lighter”, more affirmative reinterpretation of the metal spirit expressed through energetic, exuberant, and celebrative music.

Influences

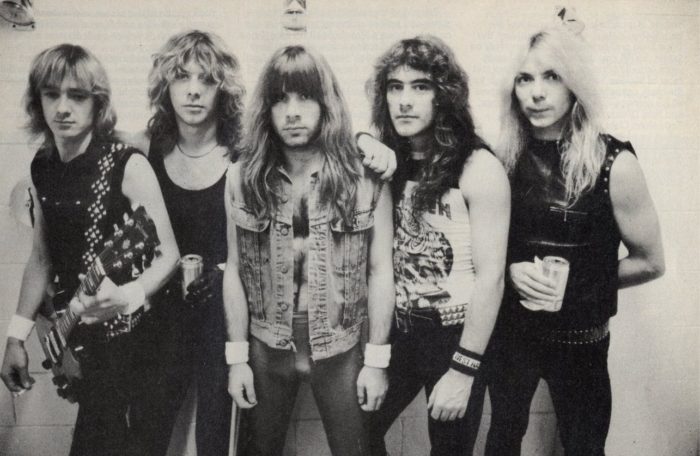

Unlike speed-, death- and black metal, power metal has retained close stylistic bonds to the music of prominent NWOBHM bands. Particularly Iron Maiden’s epic/anthemic, riff-centered compositions coupled with non-bluesy/modal, guitar-based dual harmonies, and soaring, tenor-range vocals has exerted a long-standing influence on power metal bands. A possible exception to the pivotal role of the riff can be found among some of the softer European-styled bands, where riffing is relegated to a mainly accompanying role vis-a-vis lead melodies provided either by lead guitar, vocals or keyboard instruments. Power metal’s structural principles are likewise derived from the NWOBHM, with songs customarily evolving according to verse/chorus templates enhanced with transitional sections such as contrasting riff-segments, lengthy lead guitar duels, intros/interludes/outros, etc. However, as in the case of Iron Maiden, it’s not uncommon to find at least one longer, multi-sectional piece on a power metal album; although even these tend to be built according to conventional heavy metal structures rather than adopting the narrative approach of Black Sabbath’s core works or fully-formed death- and black metal.

The central position of guitar soloing in 80s metal is also kept intact, and these tend to be either similar in character to those heard in Iron Maiden’s and Judas Priest’s main bodies of work, or inspired by the 1980s neoclassical school of guitar wizardry represented by Yngwie Malmsteen.

Other influential bands of the early 1980s were the NWOBHM-affiliated Satan and Denmark’s Mercyful Fate, whose gritty yet elegant compositions walked the line between heavy metal, progressive and proto-speed metal and worked as a crucial link between older heavy metal and ensuing developments. While not as important in the grander schemes, many of the German bands were influenced by Accept, whose music showed clear affinities with the NWOBHM (if crossed with AC/DC and Motörhead). Some writers has even gone as far as implying that Teutonic power metal can be traced back to so-called schlager music, given the emphasis placed on singalong-choruses and happy-go-lucky musical and lyrical attributes among prominent German bands.

Another decisive factor in the development of power metal as a distinctive sub genre was the incorporation of techniques from speed metal. The seeds of what would become speed metal were, as noted above, already sown in the NWOBHM, but it would be difficult to imagine power metal in its current form without the influence of early speed metal proper. Crucial in this context is power metal’s extensive adaption of speed metal-styled palm-muting, pedal tones and increased tempo. Given the ubiquity of such techniques in speed metal, it would be essentially unnecessary to speculate about the role of individual bands. More important is to recognize that power metal didn’t assimilate speed metal’s techniques or compositional methods in their entirety, but kept closer to heavy metal practices. European power metal especially tends to favor a “cleaner,” more delicate expression than that of percussive and hardcore punk-infused speed metal bands. But as the 1990s dawned, power metal bands would begin endorsing some of the techniques pioneered by death- and black metal bands as well. This tendency escalated further as musicians previously active within death- or black metal joined the power metal camp, with results ranging from interesting (Immortal’s At the Heart of Winter) to the disastrous (Death’s Sound of >Perseverance).

Staying true to its roots, power metal bands gladly embraces lyrical themes focused on fantasy and liberation from the confines of society, paired with the passionate, to the point of melodramatic aspects of heavy metal. In addition to the Iron Maiden connection, previous writers on the subject has acknowledged the inspirational role of selected 1970s hard rock and heavy metal acts as forerunners of fantastic or medievalist-derived themes, but also in terms of musical influence. Prime actors of the 1970s include Richie Blackmoore’s Rainbow featuring metal lyricist extraordinaire Ronny James Dio on vocals, early Judas Priest, Uriah Heep and, to a lesser extent, Queen – all of which dabbled with the type of fantastic lyricial themes and/or grandiloquent musical expressions that would become central to much of power metal to follow. Although writing about fantasy, sci-fi and history are hardly unique to metal music, no other subgenre is so closely tied up with such themes. As for the musical influence of 1970s music, it seems to be more a question “inspiration by proxy” passed on through the NWOBHM. For example, both the neoclassical and rock-tinged elements of power metal was inherited via NWOBHM bands who reincorporated certain aspects of rock music that Black Sabbath had previously discarded.

Taxonomy

When writing about early power metal it is important to emphasize that the term was, like many other genre delineations, quite floating in its original meaning and only later became an established subgenre. The exact origins of the term is unclear except that it is was first used no later than 1982 as a title for Metallica’s third (?) demo tape. What we do know is that the name power metal was met with skepticism by at least some of the members of Metallica who objected to the title. Perhaps due to guilt by association, as it highlighted connotations to “power ballad”, “power pop”, etc. The term would eventually catch on though, first among US bands and later on in Europe.

Rather than delving into the myriads of stylistic significations maintained by fans, journalists and record labels, let’s put focus on the most fundamental distinction related to power metal as a subgenre. Power metal in its earliest definable form can refer to either US or European power metal, which in their original incarnation wasn’t identical. US power metal refers to early-1980s North American heavy metal bands that formed in the wake of the NWOBHM, whether or not they embody the general characteristics commonly associated with power metal today. US power metal (abbreviated USPM) was, like the NWOBHM, a movement rather than a style or subgenre. This explains why bands as seemingly diverse as Brocas Helm, Cirith Ungol, Fates Warning, Manowar and Metal Church are all habitually grouped as power metal without due reservation. European power metal on the other hand appeared in a more unified manner around in the mid-1980s, and is more closely related to our contemporary notion of the subgenre. US and European power metal would over time coalesce into an increasingly unified grouping while still retaining their individual characteristics, but it is important to stress this distinction in order to avoid unnecessary confusion.

Concluding Remarks

The following two parts of this article series will take a closer look at the characteristics and subsequent development of the two major strands of the subgenre: European- and US-styled power metal respectively. This will be executed in a slightly different manner than what is usually the case. In the meantime, if there’s anything additional that deserves to be mentioned about the origins of power metal, feel free to share in the comments below!

Suggested Listening:

Origins and Influences:

Judas Priest – “The Ripper” & “Tyrant”from Sad Wings of Destiny (1976)

Rainbow – “Kill the King” & “Gates of Babylon” from Long Live Rock’n’Roll (1978)

Iron Maiden – “Quest for Fire” & “Sun and Steel” from Piece of Mind (1983)

Satan – “Trial by Fire” & “Break Free” from Court in the Act (1983)

Metallica – “The Four Horsemen” and “Metal Militia” from Kill ‘Em All (1983)

Kreator – “Endless Pain & Total Death from Endless Pain (1985)

Early US Power Metal:

Queensrÿche – “Queen of the Reich” from Queensrÿche (1983)

Jag Panzer – “Generally Hostile” from Ample Destruction (1984)

Omen – “Death Rider” from Battle Cry (1984)

Savage Grace – “Master of Disguise” from Master of Disguise (1985) (editor’s note: best artwork ever)

Early European Power Metal:

Helloween – “Murderer” from Helloween (1985)

Running Wild – “Mordor” from Branded and Exiled (1985)

Blind Guardian – “Guardian of the Blind” from Batallions of Fear (1988)

To be continued!

Tags: accept, Angel Witch, black sabbath, blind guardian, britain, Dio, Europe, German rock, Heavy Metal, hellhammer, helloween, Introduction to Power Metal, iron maiden, jag panzer, judas priest, kreator, mercyful fate, metal history, metallica, NWOBHM, Omen, power metal, Queen, queensrÿche, rainbow, Ronny James Dio, Running Wild, Satan, Savage Grace, slayer, traditional heavy metal, United States, Uriah Heap, US Power Metal, USPM, Yngwie Malmsteen

First the Rob Halford story, and now this.

tl;dr

US power metal: heavy metal part 2

European power metal: heavy metal minus the balls

Pretty much. I wonder if Therion ever did anything decent after death metal. From what I’ve heard, no.

Gothic Kabbalah is ok. Kinda like a metal version of Cocteau Twins.

No! Gothic Kabbalah is carnival music……

100% accurate.

Get fucked, Gamma Ray, Blind Guardian and Running Wild have more balls than every single metal band formed after 95 combined.

And anyone who says power metal is a no-no for gateway for metal needs their teeth knocked out.

https://www.deathmetal.org/article/of-power-metal-and-other-tales/

Wtf does “rudimentary but comprehensive” mean? I don’t expect literary geniuses here but come on already

Rudimentary but comprehensive means functional without any technological or academic sophistication

Like using a baseball bat as weapon

I’m sorry your imagination is broken

Sun and Steel and Quest for Fire are the worst tracks on Piece of Mind. I highly doubt Blind Guardian was listening to those as much as they were Metallica in the 80s. Those tracks are so cringe even the kinda wimps who go to Wacken skip em

every time I hear any power metal band (for example, Jag Panzer), the FIRST tracks they always remind me of are Sun and Steel, and Quest for Fire.

I like Sun and Steel, so power metal bands that sound like that get a pass from me.

“with results ranging from interesting (Immortal’s At the Heart of Winter) to the disastrous (Death’s Sound of Perseverance)”

Heart of Winter WAS great, at first,for some years, but kind of like bubblegum rock, when overplayed a LOT at home, you return to it only when nostalgic.

any DEATH-post 1990 – who cares.

Overall, very well composed/written article on power metal.

Helloween had some interesting music in their early years, but other than that, the only ‘power’ Metal band worth anything is Blind Guardian. Throw everything else in the toilet.

Iced Earth’s, Night of the Stormrider is pretty good too.

This was a really, really refreshing article. ¡Thank you!