Arthur Schopenhauer once wrote that there were three kinds of authors: those who write without thinking, those who think as they write, and those who write only because they have thought something and wish to pass it along.

Arthur Schopenhauer once wrote that there were three kinds of authors: those who write without thinking, those who think as they write, and those who write only because they have thought something and wish to pass it along.

Similarly, it is not hard to produce a decent heavy metal album. You cannot do it without thinking, but if you think while you go, you can stitch those riffs together and make a plausible effort that will delight the squealing masses.

But to produce an excellent heavy metal album is a great challenge. It’s also difficult to discuss, since if you ask 100 hessians for their list of excellent metal albums, you may well get 101 different answers. Still, all of us acknowledge that some albums rise above the rest.

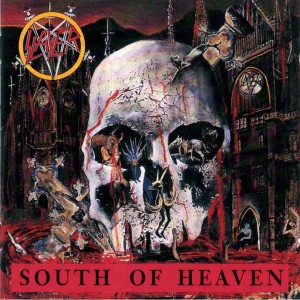

South of Heaven is to my mind such an album because it hits on all levels. Crushing riffs: check. Intense abstract structures: check. Overall feeling of darkness, power, evil, foreboding and all the things forbidden in daylight society: check. But also: a pure enigmatic sublime sense of purpose, of an order beneath the skin of things, resulting in a mind-blowing expansion of perspective? That, too.

Slayer knew they’d hit the ball out of the park with Reign in Blood. That album single-handedly defined what the next generations of metal would shoot for. It also defined for many of us the high-water mark for metal, aesthetically. Any album that wanted to be metal should shoot for the same intensity of “Angel of Death” or “Raining Blood.” It forever raised the bar in terms of technique and overall impact. Music could never back down from that peak.

However, the fertile minds in Slayer did not want to imitate themselves and repeat the past. Instead, they wanted to find out what came next. The answer was to add depth to the intensity: to add melody — the holy grail of metal has since been how to make something with the intensity of Reign in Blood but the melodic power of Don’t Break the Oath — and flesh out the sound, to use more variation in tempo, to add depth of subject matter and to make an album that was more mystical than mechanical.

Only two years later, South of Heaven did exactly that. Many fans thought they wanted Reign in Blood: The Sequel (Return to the Angel of Death) but found out that actually, they liked the change. Where Reign in Blood was an unrelenting assault by enraged demons, South of Heaven was the dark forces who infiltrated your neighborhood at night, and in the morning looked just like everyone else. It was an album that found horror lurking behind normalcy, twisted sadistic power games behind politics, and the sense of a society not off course just in politics, economics, etc. but having gone down a bad path. Having sold it soul to Satan, in other words.

The depth of despair and foreboding terror found in this album was probably more than most of us could handle at the time. 1988 was after all the peak of the Cold War, shortly before the other side collapsed, but Slayer wasn’t talking about the Cold War. For them, the problem was deeper; it was within, and it resulted from our acceptance of some kind of illusion as a force of good, when really it concealed the lurking face of evil. This gave the album a depth and terror that none have touched since. It is wholly unsettling.

Musically, advancements came aplenty. Slayer detached themselves from the rock formula entirely, using chromatic riffs to great effectiveness and relegating key changes to a mode of layering riffs. Although it was simpler and more repetitive, South of Heaven was also more hypnotic as it merged subliminal rhythms with melodies that sounded like fragments of the past. The result was more like atmospheric or ambient music, and it swallowed up the listener and brought them into an entirely different world.

South of Heaven was also the last “mythological” album from Slayer. Following the example of Black Sabbath’s “War Pigs,” Slayer’s previous lyrics found metaphysical and occult reasons for humanity’s failures, but never let us off the hook. Bad decisions beget bad results in the Slayer worldview, and those who are happiest with it are the forces of evil who mislead us and enjoy our folly, as in “Satan laughing spreads his wings” or even “Satan laughs as you eternally rot.” The lyrics to “South of Heaven” could have come from the book of Revelations, with their portrayal of a culture and society given to lusts and wickedness, collapsing from within. (Three years later, Bathory made the Wagnerian counterpoint to this with “Twilight of the Gods.” Read the two lyrics together — it’s quite influential.)

Most of all, South of Heaven was a step forward as momentous as Reign in Blood for all future metal. We can create raw intensity, it said, but we need also to find heaviness in the implications of things. In the actions we take and their certain results. In the results of a lack of attention to even simple things, like where we throw our trash and how honest we are with each other. That is a message so profoundly subversive and all-encompassing that it is terrifying. Basically, you are never off the hook; you are always on watch, because your future depends on it.

Slayer awoke in many of us a sense beyond the immediate. We were accustomed to songs that told us about personal struggles, desires and goals. But what about looking at life through the lens of history? Or even the qualitative implications of our acts? Like Romantic poetry, Slayer was a looking glass into the ancient ruins of Greece and Rome, onto the battlefields of Verdun and Stalingrad, and even more, into our own souls. Reign in Blood broke popular music free from its sense of being “protest music” or “individualistic” and showed us a wider world. South of Heaven showed us we are the decisionmakers of this world, and without our constant attention, it will burn like hell itself.

I remember from back in the day how many of my friends were afraid of South of Heaven. The first two Slayer albums could be fun; Reign in Blood was just pure intensity; South of Heaven was awake at 3 a.m. and existentially confused, fearing death and insignificance, Nietzschean “fear and trembling” style music. It unnerved me then and it does still today, but I believe every note of it is an accurate reflection of reality, and of the charge to us to make right decisions instead of convenient ones. And now with Slayer gone, we have to compel ourselves to walk this path — alone.

Tags: goat, slayer, south of heaven

I’ve probably listened to South of Heaven more than any other Slayer album, and I have to say, I agree with this article. 80s Slayer did so much for metal, it was pretty obvious that a next generation wouldn’t last so long with Slayer being the first one there to say so much. This album predates some of the stuff on Soulside Journey, Lost Paradise, Blessed are the Sick… The melodies were no longer indebted to NWOBHM or early punk-metal crossovers, they were built from fragments of a motif(s), like how Incantation built Onward to Golgotha. Sad that with so much visibility, people just “didn’t get it” and wanted the “shocking speed” of Reign in Blood for poser-ish scene cred and whatnot, seeing as how most people are of the opinion that “every Slayer album sounds the same. If you liked old Slayer, well, it’s Slayer!” (even though Diabolus in Musica nu-metal isn’t to be found on Show No Mercy’s NWOBHM, Divine Intervention had simple structures and groove/mosh emphasis, etc.). True, fully formed, early 90s death metal had it’s foundation built with this album. Engaging, energetic music that felt like unimaginable worlds being forced into your subconcious for exploration. An album that was more like an experience than a collection of songs.

Well said. I agree, though I won’t deny being biased — SoH was the first Slayer album I heard. The “evil melodies” that Hanneman so excelled at writing are in full force on this record.

I think this article hits the nail on the head; very well stated. ‘South of Heaven’, looking back, seems to be the peak of their musical genius. The part that amazes me to this day is how it all just came naturally. They just knew how to make these great albums.

Interesting, I thought the DLA’s stance was always that Hell Awaits was the definitive Slayer album. Glad to know I’m not the only one who consider South of Heaven their best.

Anyway, this is the type of article that keeps me coming back. The lens of history bit was spot-on: SoH is neither optimistic nor pessimistic like most music, but rather realistic.

Home run, Brett. THIS-

“we need also to find heaviness in the implications of things. In the actions we take and their certain results. In the results of a lack of attention to even simple things, like where we throw our trash and how honest we are with each other. That is a message so profoundly subversive and all-encompassing that it is terrifying.”

Thanks! I have to give credit to Kant for whacking my head awake to this type of thinking. His concept of “radical evil” shaped my knowledge of the world after it in a profound way. I also like his ultimate defense of a priori knowledge as “intuition.”

How do you reconcile your nihilistic approach to morality with the categorical imperative?

The nihilistic approach to morality is to measure each thing by its consequences, not intentions. This would be a form of the categorical imperative, namely that if everyone did the same, we’d have a lot less of a moral filter between us and reality and thus, a more active morality.

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/kant-moral/#TelDeo

My understanding of the CI is that an act is moral when the will behind it is in accordance with reason, that is, would the act make sense if made into a universal law? And by ‘make sense’ I mean logically, not empircally or morally. As in, the concept of ownership could not exist if stealing were made in to universal law, thus invalidating stealing. Saying that the CI measures things by its consequences seems to be a misrepresentation, as it is not measuring anything, such as moral worth, but sees if it makes sense or not.

(pardon if this makes no sense, I haven’t studied philosophy in years).

At the time I thought RIB was their best but this one ended up withstanding the test of time better. There are a number of moments on RIB that sound like skate thrash and that’s ok but it has paled after 27 years.

I think most old fans would agree that after SOH, Slayer jumped the shark. Seasons had lots of speed but for some reason it didn’t have the real unrelenting darkness SOH did. After Seasons it was a fairly rapid slide downhill and they never recovered, though they certainly deserved their huge popularity.

The problem I have with this album is that after “Ghost of War”, the album had just fillers. Every time I listen to “Spill the blood “, it just doesn’t feel right… Altar of madness is a far revolutionary and deserves to be the greates of them all

The lyrics to praise of death seem to carry the theme of this album as well:

http://www.darklyrics.com/lyrics/slayer/hellawaits.html#4

Maybe an article on Slayer’s lyrical contributions to metal should be in order, including the decline in inspiration following Seasons in the Abyss as far as topics are concerned. I agree with this album being a great conclusion to Slayer’s extreme trilogy (HA,RiB,SoH), almost mirrored in Darkthrone’s black metal trinity in the way that the final album is more meditative.

There are good arguments here for why SoH might be the best metal album of all time; however, I think we may have forgotten the rejoinder to this line of thinking: Hell Awaits ; )

This post might well inspire me to write similar articles about the other early Slayer albums, if I get the time soon. This is a prime example of the kind of stuff the DLA should be producing!